Credit to Noncorporate Businesses Remains Tight

Firms use credit to finance production, working capital, investment in physical capital, and research and development. All these activities are important for the functioning of the economy. In fact, as argued in recent research, there is a strong connection between the development of credit markets and that of the economy.1

On June 5, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System published the Financial Accounts of the United States for the first quarter of 2014. This article uses data from that publication to analyze the use of credit by nonfinancial businesses since the financial crisis of 2008. The main finding is that the evolution of outstanding liabilities has been very different for corporate and noncorporate businesses, with a remarkable stagnation in credit to noncorporate businesses.

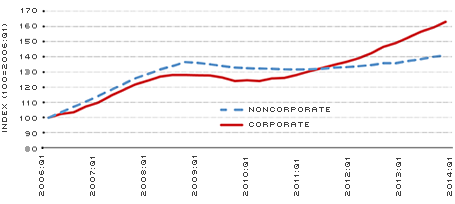

Figure 1 displays the value of outstanding liabilities of corporate and noncorporate businesses. Since their previous peak (during the financial crisis), liabilities of corporate businesses increased about 20 percent, while liabilities of noncorporate businesses increased only 4 percent. These patterns may be important to understand the strength of the recovery if we take into account the well-established connection between the functioning of credit markets and that of the aggregate economy. Recent research shows that disturbances in financial markets may be an important cause of business-cycle fluctuations.2

Corporations are distinguished from noncorporations in two critical ways: (i) the financial sources to which they have access (corporations can issue shares in the stock market and can borrow and lend by issuing bonds, while noncorporations can't do either) and (ii) the ownership and control structure (a corporation is owned by shareholders but is typically run by a separate group of managers, while noncorporations are typically owned by one or two individuals who also perform as managers).3 The first element is important to understand the differences in the type of liabilities available for these two groups of firms.

The main components of liabilities for both corporate and noncorporate businesses are credit instruments (e.g., commercial paper, corporate bonds, depository institution loans and mortgages). They represent about 60 percent and 70 percent of the liabilities of corporations and noncorporations, respectively. The rest are trade payables, which are liabilities owed to suppliers for purchases or services rendered; tax payables, which are taxes that a company owes as of the balance sheet date; and others.

Figure 2 displays the evolution of credit market instruments. The difference between corporations and noncorporations is quite striking. Since the financial crisis, corporations increased the value of outstanding credit market instruments by 27 percent, while the same variable increased by only 3 percent for noncorporations.

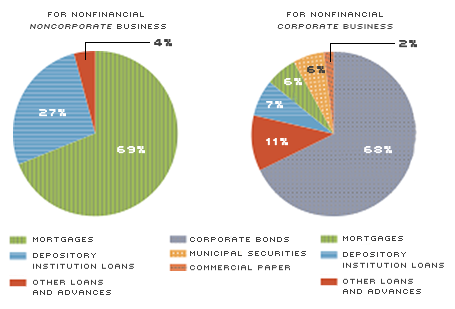

To understand the evolution of credit market instruments, consider their composition, as shown in Figure 3. For noncorporate businesses, most of the debt is composed of mortgages (69 percent) and loans from depository institutions (27 percent). In contrast, 68 percent of the credit market liabilities of corporations are corporate bonds, which are not available to noncorporate businesses.

The table displays the growth of loans from depository institutions, mortgages and corporate bonds. Recall that the first two are the most important credit instruments used by noncorporate businesses, while the last one is available only for corporations. The trend in loans from depository institutions and in mortgages since the financial crisis is very sluggish for both types of businesses. Actually, for these two instruments, growth was negative for corporate businesses and slightly positive for noncorporate businesses. The key difference is that noncorporate businesses rely on these instruments, while these instruments are much less important for corporations, as shown in Figure 3. Actually, the strong recovery of credit for corporations is due to the fast growth of corporate bonds; their growth has increased at an average annual rate of 10 percent since 2008:Q4.

Overall, credit to noncorporate businesses remains tight. This phenomenon is mostly accounted for by the sluggish recovery of loans from depository institutions and mortgages, which are very important for this type of business. Tight credit may be affecting the day-to-day operations of noncorporate businesses since credit is important for growth. Future research should focus on trying to find out the reasons for the weak recovery of lending by banks and other depository institutions.

Total Liabilities of Nonfinancial Businesses

Click to enlarge [back to text]

SOURCE: Financial Accounts of the United States, published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Value of Outstanding Credit Market Instruments

Click to enlarge [back to text]

SOURCE: Financial Accounts of the United States, published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Components of Credit Market Liabilities, by Instruments, 2013

Click to enlarge [back to text]

SOURCE: Financial Accounts of the United States, published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Endnotes

- See, for example, Greenwood, Sánchez and Wang. [back to text]

- See Shourideh and Zetlin-Jones. [back to text]

- See Magill and Quinzii, Chapter 6, Section 31, for a thorough discussion. [back to text]

References

Greenwood, Jeremy; Sánchez, Juan M.; and Wang, Cheng. "Quantifying the Impact of Financial Development on Economic Development," Review of Economic Dynamics, January 2013, Vol. 16, No. 20, pp. 194-215.

Magill, Michael; and Quinzii, Martine. Theory of Incomplete Markets, Vol. 1. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996.

Shourideh, Ali; and Zetlin-Jones, Ariel. "External Financing and the Role of Financial Frictions over the Business Cycle: Measurement and Theory." Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, December 2012.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us