President's Message: A Mismatch: Close to Macroeconomic Goals, Far from Normal Monetary Policy

By conventional metrics, the U.S. economy is approaching normal conditions in terms of the two main macroeconomic goals assigned to the Federal Reserve—price stability and maximum sustainable employment. The monetary policy stance of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), however, has not yet begun to normalize. Current policy settings are far from normal, and the normalization process will take a long time. Therefore, normalizing may need to begin sooner rather than later if macroeconomic conditions continue to improve at the current pace.1

Over the past five years, U.S. unemployment has been high, although it has generally been improving since it reached 10 percent in October 2009. In September 2014, the unemployment rate stood at 5.9 percent, down from 7.2 percent a year earlier. Inflation was surprisingly low from the second quarter of 2013 through the first quarter of 2014, but recent readings have moved closer to the FOMC's 2 percent target. The inflation rate, as measured by the year-over-year percent change in the personal consumption expenditures price index, was 1.5 percent in August.

In recent years, the FOMC has used two main tools to achieve its dual mandate—short-term interest rate policy (the federal funds rate) and quantitative easing (QE). The target for the federal funds rate has remained near zero since December 2008. Meanwhile, the Fed's balance sheet is still large and increasing, although the current asset purchase program (QE3) is winding down. The size of the balance sheet, at more than $4 trillion, is roughly 25 percent of U.S. nominal gross domestic product (GDP).

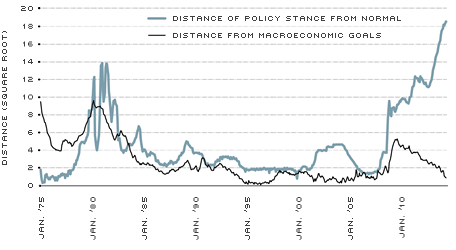

The figure illustrates a measure of how far the economy's performance has been from the FOMC's macroeconomic goals since 1975 and a measure of how far the stance of monetary policy has been from normal. The former, based on inflation and unemployment, currently shows a low value that is close to precrisis levels.2 The latter, based on the federal funds rate and the size of the balance sheet relative to GDP, shows the opposite. In other words, the macroeconomic goals are close to being met, whereas monetary policy settings have a long way to go before being close to normal.

While this mismatch is not causing macroeconomic problems today, it may cause problems in the years ahead as the economy continues to expand. One risk is that inflation would return. If that does happen, the FOMC would have to adjust policy faster and more aggressively than it usually does, as inflation tends to be difficult to get under control. The other main risk is that financial market bubbles could develop. Macroprudential policies alone are probably not sufficient to keep a bubble under control; these policies must be combined with monetary policy that is consistent with financial stability, as well as our macroeconomic goals.

Up to now, relatively low inflation and relatively weak labor markets have suggested a later start to normalizing monetary policy, but stronger-than-expected data may change this calculus in the months and quarters ahead. Over the next few years, the objective will be to execute monetary policy normalization without creating excessive inflation or substantial financial stability risks.

Distance from Goals vs. Distance from Normal Policy

Click to enlarge [back to text]

SOURCES: Federal Reserve Board, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics and author's calculations; data obtained from FRED and Haver Analytics.

NOTES: Details on the functions used to measure these distances can be found in my presentation on July 17, 2014. The figure, which is an updated version of a chart from that presentation, shows the square root of the function values from January 1975 to June 2014.

For these calculations, the normal policy stance refers to historical averages for the federal funds rate and the size of the balance sheet relative to GDP. The macroeconomic goals refer to the FOMC's inflation target and the midpoint of the central tendency of the longer-run projection for unemployment, as of the FOMC's September Summary of Economic Projections.

Endnotes

- This column is based on my presentation on July 17, 2014, "Fed Goals and the Policy Stance." See http://research.stlouisfed.org/econ/bullard/fed-goals-and-the-policy-stance. [back to text]

- For a broader measure of the labor market, one could use the labor market conditions index from staff at the Federal Reserve Board. However, the results would be similar because there is a high correlation between this index and the unemployment rate. See Chung, Hess; Fallick, Bruce; Nekarda, Christopher; and Ratner, David. “Assessing the Change in Labor Market Conditions,” FEDS Notes, May 22, 2014. [back to text]

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us