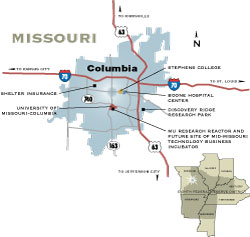

Community Profile: Life Sciences Help College Town of Columbia, Mo., Evolve

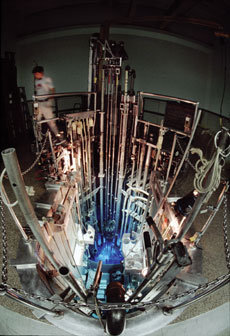

Founded in 1839 as the first public university west of the Mississippi River, the University of Missouri–Columbia is known for its rich history in fields ranging from journalism to law and medicine, as well as for being one of the few universities with a nuclear reactor for research.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1968, two biochemistry graduate students and their professor sowed the seeds for yet another specialty, one that is now playing a key role for the university and the Columbia region.

Dr. Charles Gehrke and graduate students Jim Ussary and David Stalling decided to put their ideas and experiments to the real-world test by forming their own company, Analytical Bio-Chemistry (ABC) Laboratories. They kept their venture here, adjacent to the city and in the shadows of Mizzou, as the university is known.

Almost 40 years later, ABC is a rapidly growing firm that helps pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, animal health and chemical companies ensure the safety and effectiveness of their products, as required by regulatory agencies. Nearly all of ABC’s $25 million revenue comes from out-of-state firms.

The company is now on the verge of another major move. In about a year, it will become the first tenant of the university’s Discovery Ridge Research Park. At ABC’s new $15 million facility, it will employ 500 people––double the current total.

“If our presence here can help attract additional life sciences tenants, it will be a win-win situation that will benefit our company and the regional economy,” says Byron Hill, the head of ABC.

It is also hoped that some of ABC’s own research will spawn new firms that will locate at the new research park.

Boone County, home to Columbia, is showing its confidence in ABC by providing the company with a Chapter 100 bond incentive that could save the firm as much as $15 million in property taxes over the next 10 years. ABC is the first Boone County firm to receive incentives from the county in 30 years.

Mining Profit from Invention

The ABC expansion is only the latest way in which the university, city, county and business leaders are trying to transform the area into a hub of scientific innovation and biotechnology startups.

Another key building block was put in place in 2004 when Mizzou opened its $60 million Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center. Bond, a U.S. senator from Missouri, helped obtain a $30 million grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the project. The National Institutes of Health and Monsanto Corp., a St. Louis agricultural research and development firm, helped foot the rest of the bill.

|

The rotunda of Jesse Hall, the main administration building, towers over the center of the Mizzou campus. (Photo copyrighted by the Curators of the University of Missouri.) |

|

The university’s nuclear reactor. The university is one of the few in the country to have a reactor for research. (Photo copyrighted by the Curators of the University of Missouri.) |

|

Analytical Bio-Chemistry Laboratories, seen in photos above, will move in about a year into the university’s new Discovery Ridge Research Park. In larger photo is Byron Hill, president and CEO. ABC was founded almost 40 years ago by a university professor and two of his students. (Large photo courtesy of The Columbia Daily Tribune) |

|

The Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center, which opened in 2004. |

The Life Sciences Center forms the foundation for the university’s economic development strategy: hatch ideas, patent them and turn them into startup businesses that stay in the area and fuel regional economic growth. The expectation is that such an environment will, in turn, attract more faculty and students with the same innovative bent.

“The engine driving this deal is the university,” says David Meyer, marketing director for Columbia’s Regional Economic Development Inc. (REDI), a nonprofit, public-private agency. “They have recently made economic development one of their main priorities, and they are looking to mine some technology and innovation from their research dollars. Instead of licensing it to an out-of-state company, they’re wanting to foster more innovation and entrepreneurship in Columbia.”

In the past decade, 60 patents have been granted out of 150 filed by university researchers, according to campus officials, generating nearly $18 million in licensing revenue and spawning more than 20 startup companies. Of those startups, three are successful, full-fledged companies that have relocated elsewhere, with two moving to California and another now located in Boston, says James Coleman, Mizzou’s vice chancellor for research. The remaining startups are still in the early stages of getting their businesses up and running, he says.

“We are just now creating the programs and infrastructure to keep these new businesses in Columbia; so, we are very hopeful that some of these other startups will stay here,” Coleman says. “It’s an exciting time.”

To keep the momentum going, Mizzou has joined forces with its Columbia neighbor, Stephens College, and with the city of Columbia to form a planning and development partnership and coordinate future land use around the boundaries that the city and the schools share. Mizzou and the city are each committing $50,000 to the partnership, with the initial funding slated for a land-use study.

In addition, Columbia economic development officials earlier this year formed Centennial Investors, a group of 35 “angel investors” who specialize in financing high-risk business startups.

“The hope is that the ideas the university researchers patent here will stay here,” says Columbia Chamber of Commerce President Don Laird. “These investors may look at 50 to 70 ideas to come up with four or five good deals.”

New companies that are formed will likely be housed at either Discovery Ridge or the Mid-Missouri Technology Business Incubator, an $8.7 million university-sponsored facility in the works. Columbia’s biotechnology-related efforts are attracting national attention as well: Mizzou is one of 18 semifinalists from around the nation vying to house the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s planned $450 million Bio and Agro-Defense Facility. Mizzou’s competitors for the facility—which would be used to investigate infectious diseases and bioterrorism threats— range from other universities to laboratories and bio-agro consortiums. A winner will be announced in early 2008.

Life as a College Town

Even without the new emphasis on high-tech and biotech, Mizzou is big business. With 28,000 students, the university generated $1.3 billion in revenue just in the past fiscal year.

“Think of us as a billion-dollar company with 12,000 employees,” says Provost Brian Foster. “There aren’t many of those in the state. We bring in revenue, collaborate with other firms and government enterprises in the state and prepare the work force of the future.”

That mix goes a long way in explaining why Columbia routinely pops up on national lists of best places to live, in magazines ranging from Forbes to Modern Maturity.

The town is along Interstate 70 almost midway between St. Louis and Kansas City; only 30 minutes away is the state capital of Jefferson City. Columbia’s population has grown slowly and steadily over the past two decades, about 1.5 percent to 2 percent per year, says Laird. “For the most part, our infrastructure has been able to keep up, and we haven’t run into the logistical problems that cities can face with a sudden population influx,” he says.

In addition to its focus on the university, the region has become a hub for insurance and health care. Shelter Insurance has its headquarters in Columbia, and State Farm has one of two regional offices there. Each insurance company employs more than 1,000 people in Columbia. The Missouri Farmers Association insurance co-op is also housed in Columbia, along with three other smaller insurance firms.

Health care is an even bigger industry, with five hospitals and 850-plus physicians in the area. While travelers from farther away may come to Columbia to visit Mizzou, mid-Missourians often focus their trips on a doctor visit and stay to spend money at restaurants and stores.

However, with three Wal-Marts and a Sam’s Club (Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton attended Mizzou and several family members have roots in the region), Columbia isn’t focusing on attracting more retail, says Geni Alexander, a spokeswoman for REDI. “We’re trying to get businesses where people can earn a good living to spend money,” she says. “Our feeling is that if we do that, the retail will come afterward.”

Manufacturing isn’t a major focus either, though firms such as 3M, Oscar-Meyer and Quaker Oats have facilities in Columbia.

“We’re never going to be the type of city that, say, goes out and attracts an automobile plant,” says Columbia City Manager Bill Watkins. “That’s just not our strength and not our labor force. Biotechnology, plant science and animal science—that’s where the jobs will be 10 or 20 years from now.”

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us