Suburban Expansion: District Growth Rate Tops National Average, Census Shows

According to the 2000 census, American suburbs have grown faster since 1990 than their corresponding cities. And suburbs in the Eighth District are expanding at a stronger pace than in the nation as a whole.

This is the second in a series of articles on changes in the District over the past decade as revealed by the census. Studying census data allows for a better understanding of the patterns of economic growth in our region.

This article documents the patterns of urbanization for 13 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the District, using population and housing data. The article also lays the groundwork for analyzing some of the major issues of suburban growth—such as whether this expansion is really the problem portrayed by many policy-makers and interest groups. Among economists, the issue is far from settled.

District Suburban Population Growth

The Eighth District is much less "metropolitan" than the rest of the country. In the United States in 1990, 79.8 percent of Americans lived in metropolitan areas. Ten years later, that figure inched up to 80.3 percent. In contrast, only 51.1 percent of the District's population lived in an MSA in 1990 and just 51.5 percent in 2000. (The 13 MSAs considered in this analysis lie entirely within the Eighth District boundaries, with the exception of Fort Smith, Ark. This MSA extends into Sequoyah County in Oklahoma.)

Using data on population and housing, a straightforward indicator of suburban expansion, or "sprawl," is the difference in growth experienced in central cities and their suburbs between 1990 and 2000.1 Among District MSAs, suburban population grew more than twice as fast as population in the corresponding central cities. On average, population in the suburbs grew by 1.8 percent at compound annual rates2 and by only 0.8 percent in the central cities. This suburban expansion was stronger in the District than in the United States, where suburban population grew by 1.5 percent annually, compared to 0.9 percent in central cities.

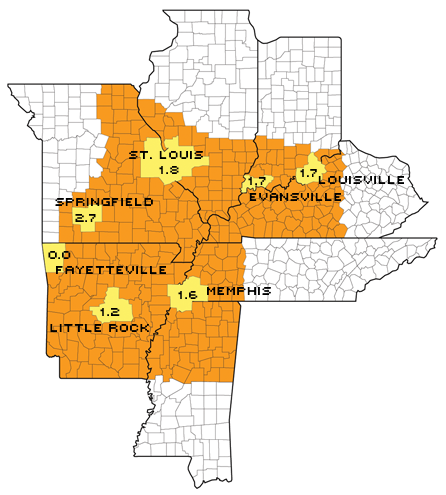

The companion map ranks major MSAs in terms of the difference in average annual growth rates between suburbs and their central cities. From this perspective, the highest difference was observed in Springfield, Mo., where suburban growth outpaced central city growth by 2.7 percentage points. The St. Louis MSA, part in Missouri and part in Illinois, ranked second with a difference of 1.8 percentage points. Tied for third place are the Evansville-Henderson MSA and the Louisville MSA, both of which straddle the Kentucky-Indiana border. Both had a difference of 1.7 percentage points. The Memphis MSA, which touches Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi, followed closely with a difference of 1.6 percentage points. In fifth place was Little Rock, Ark., with a difference of 1.2 percentage points. In just two MSAs, the central city grew faster than the suburbs—but just a hair faster. In Jackson, Tenn., the city grew 0.7 percentage points faster. In Columbia, Mo., the city's growth outpaced the suburbs' by 0.4 percentage points.

Following the national trend, the largest relative suburban expansion in the Eighth District occurred, in general, in MSAs with large central cities. The six fastest-growing MSAs in terms of sprawl had central cities of at least 149,000 people in 2000.

Where Are New Homes Being Built?

Given the relative growth of suburbs since 1990, it is not surprising that more housing units were built in the suburbs than in cities over the same period. In the Eighth District, the average annual growth rate of housing units in the suburbs was 2.2 percent. In the cities, it was 1.0 percent. For the nation as a whole, housing units grew at average annual rates of 1.3 percent in the suburbs and 0.8 percent in the central cities. The fact that housing units grew faster than population indicates that households in the District's suburbs and cities were smaller in 2000 than in 1990.

The pattern of suburban housing growth relative to growth in the central cities closely follows the pattern of population growth: Large cities tended to have the fastest suburban housing growth. Owensboro, Ky., and Pine Bluff, Ark., were the exceptions in that they had much faster growth in suburban housing relative to their central cities. They were among the smallest MSAs in the District, however.

Is Expansion Really a Problem?

Economists identify three main factors that have reinforced suburban growth: population growth, rising household income and declining commuting costs.2 Yet migration to the suburbs ultimately reflects individuals' demand for housing space and public goods.

To an economist, the patterns of suburban expansion reflect choices made by individuals on the appropriate uses of land: If suburbs are expanding, then the benefits perceived by residents must exceed the costs they incur. Why, then, might this expansion not be socially desirable? Economics tells us that there are actually very limited scenarios where suburban expansion might be a problem, in sharp contrast to what opponents of sprawl usually maintain. One possibility is that individuals, in making their choices, do not account for all the benefits and costs that society, as a whole, ultimately derives from them.4 Economists refer to these situations as market failures because, in such cases, the market fails to allocate resources to those activities where they are valued most. In order to consider sprawl a problem, however, the extent of these failures would have to be carefully ascertained.

The main concern about suburban expansion is that it may be excessive. Economist Jan Brueckner identifies three potential market failures that explain why this may occur. First, developers may fail to take into account all the costs of public infrastructure generated by new development. In this case, the cost would not be reflected in the property tax paid by homeowners. Second, commuting may involve additional time costs when roads are congested by excessive traffic. Individual commuters do not perceive the costs imposed on others by their own use of the road. Third, in converting land to urban use, developers do not take into account intangible benefits of open spaces that might be lost by other households in areas that are already urbanized.

In all three cases, failure to account for all the costs imposed on society may lead to overuse of land resources. Brueckner remarks that remedies for these problems—except maybe accounting for the benefits of open space, which are difficult to assess because of their subjective nature—can successfully be implemented in the form of development taxes, congestion tolls or impact fees.5 These measures would then be designed to make private costs reflect the full burden of social costs. Brueckner recognizes that such policies, though efficient, may be politically unpopular.

Although developers often pay development taxes or impact fees, the fragmented nature of local governments in some metropolitan areas may lead to large expansion. That's because they follow independent fiscal programs that consider only their own costs and benefits and not the region's.

So-called smart growth policies, such as the urban growth boundary (UGB) in Portland,6 Ore., are blunt and do not attack the potentially underlying sources of excessive expansion. Ultimately, they can be harmful because they lead to denser cities and restrict access to affordable housing space, especially for the very poor, by decreasing the supply of urban land.

Conclusions

In the Eighth District MSAs, population and new homes are increasing faster in the suburbs than in the central cities. Except for some cases, faster growth tends to occur in metropolitan areas with large cities. Without additional data, it is hard to assess whether suburban expansion constitutes a problem in the District, but this article has laid out some ideas that would help identify potential problems in future analysis.

Sprawl in the Eighth District

Most of the largest cities in the Eighth District have become more sprawling since 1990. The difference between suburban and urban annual growth rates was largest in Springfield, where it was 2.7 percentage points.

SOURCE: Census 2000

Endnotes

- Suburban variables were defined subtracting the sum of central cities variables from MSA totals. [back to text]

- The compound annual rate represents the annual average rate of growth over the 10-year period we examine. [back to text]

- See Mieszkowski and Mills (1993). [back to text]

- See Brueckner (2000). [back to text]

- Impact fees are lump-sum payments made up-front by developers to cover the costs of new infrastructure. [back to text]

- The UGB is a very strict form of zoning that imposes limits on urban development around the city. [back to text]

References

Brueckner, Jan K. "Urban Sprawl: Diagnosis and Remedies." International Regional Science Review, April 2000, 23 (2), pp. 160-71.

Fulton, William; Pendall, Rolf; Nguyen, Mai and Harrison, Alicia. "Who Sprawls Most? How Growth Patterns Differ Across the U.S." The Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., July 2001.

Mieszkowski, Peter and Mills, Edwin S. "The Causes of Metropolitan Suburbanization." The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Summer 1993, 7 (3), pp. 135-47.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us