The Gender Wage Gap And Wage Discrimination: Illusion or Reality?

After more than a generation since the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 together barred employment and wage discrimination, the gap between men's and women's average earnings is still wide. In 1999, women's median weekly earnings for full-time workers were 76.5 percent of men's—a gender wage gap of 23.5 cents for every dollar earned by the median man.

Many believe that the wage gap is a good measure of the extent of gender wage discrimination, which occurs when men and women are not paid equal wages for substantially equal work. Irasema Garza, director of the Women's Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor, recently testified to the widespread nature of this view in policy-making circles. Before Congress last June, she outlined steps being taken by the current Administration to eliminate the gender wage gap. Ironically, the gap has increased since 1993, when the Administration took office. After falling steadily between 1979 and 1993, it rose in four of the six years from 1993 to 1999, ending the period a little more than one-half of a cent higher.

This uncomfortable trend, however, has little to do with a failure to fight wage discrimination. The weight of evidence suggests that little of the wage gap is related to wage discrimination at all. Instead, wage discrimination accounts for, at most, about one-fourth of the gap, with the remainder due to differences between men and women in important determinants of earnings such as the number of hours worked, experience, training and occupation. Moreover, even this one-fourth of the gap may have less to do with wage discrimination than with the accumulated effects of shorter hours and interrupted careers on women's earnings and promotion prospects. To see this, let's break the wage gap numbers down in greater detail.

Breaking Down the Numbers

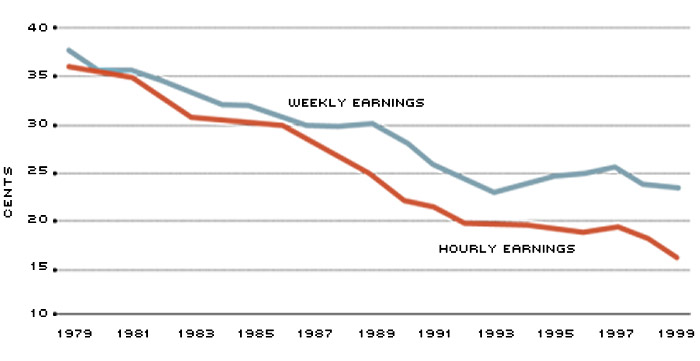

The first step in understanding the composition of the gender wage gap is to see if the correct measure of wages is being used. Because the average woman works fewer hours per week than the average man, defining the gap in terms of weekly earnings, as the Department of Labor usually does, inflates the wage gap artificially.1 Shifting the focus to hourly wages alone eliminates almost one-third of the gap: In 1999, women's median hourly earnings were 83.8 percent of men's, leaving a 16.2 cent gap in hourly earnings.

Defining the gender wage gap in terms of hourly earnings not only makes more sense statistically, but also illuminates the labor market gains made by women. As the accompanying chart shows, during the last two decades the gender gap in hourly earnings has fallen faster than the gap in weekly earnings. This has occurred as more women entered the labor force, including much larger proportions of women with children.2 Because the average woman with children works fewer hours per week, this trend has tended to increase the difference between the two measures of the gender wage gap.

Understanding the Numbers—The Gender Wage Gap, 1979-99

In 1999, women's median weekly earnings were 76.5 percent of men's, implying a gender wage gap of 23.5 cents for every dollar earned by the median man. The gap has fallen by 13 cents during the last two decades, but has actually risen since 1993. A better measure, the gap in hourly earnings, has fallen faster and more continually during the period, standing at 16.2 cents in 1999.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor

Still, the gender wage gap of 16.2 cents that remains after correcting for the number of hours worked per week is rather substantial. The next question to examine is how much of the gap is due to human capital variables—such as education and experience—and other variables—such as industry, occupation and union status—that make wages differ between any two groups of workers. A 1997 study by Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn is representative of the research done on this question. This study was relied upon in a recent analysis of the gender wage gap by the President's Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), which was subsequently cited by Director Garza in her statement to Congress.3

The Blau and Kahn study attributes 62 percent of the gap in hourly wages to such differences—one-third to differences in human capital variables, and 29 percent to differences in industry, occupation and union status. After applying these numbers to the 16.2 cent gap in hourly earnings, 6.2 cents of the gender wage gap remains unexplained.

Discrimination or Career Choices?

The unexplained, or residual, portion of the gender wage gap could be due to wage discrimination, or to other factors, including labor market variables that are difficult to account for. As the CEA study pointed out, some elements of wage determination are not adequately controlled for in existing studies. For example, primarily because of childbearing, a woman's labor market experience is more likely to be discontinuous. But little is known about the effects of this phenomenon because studies have controlled only for the total number of years in the workforce, not for discontinuities. Also unknown are the accumulated effects of shorter average hours on women's earnings.

Of course, other types of discrimination may have played a part in creating human capital and other differences between men and women. Take, for example, what has been called occupational segregation—many occupations staffed predominantly by women tend to pay less than occupations staffed predominantly by men. Is discrimination responsible for this? Or, as a study by Diana Furchtgott-Roth and Christine Stolba argues, are such occupational differences between men and women due to differences in childbearing and family responsibilities? These two differences, say the authors, account for the fact that women, on average, work fewer hours, and have more and longer gaps in their workforce participation. These differences also mean that women also tend to have greater incentives than men to choose jobs that are time-flexible, and careers in which job skills deteriorate slowest.

Which scenario is driving gender differences in occupation? Is elementary school teaching predominantly female because women tend to be shunted into teaching from the male-dominated jobs they would have preferred? Or, are women choosing elementary school teaching because it provides the job flexibility and slow job-skill deterioration that fits their lifestyle? Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between.

One way to gain insight into the unmeasured importance of childbearing is to look at the wage gap for age groups that are less likely to have children. As Blau and Kahn have reported in their more recent analysis, the hourly gender wage gap for women is smallest—5.8 cents in 1998—for those aged 18-24. Furchtgott-Roth and Stolba report that among those who are aged 27 to 33 and have never had a child, women's median hourly earnings are 98 percent of men's, a gender wage gap of only 2 cents. Note that these numbers are not adjusted for differences in human capital and other variables, which would make the gaps even smaller.

Eliminate the Gender Wage Gap?

Is one to take from the numbers presented here that the gender wage gap of 23.5 cents is mostly an illusion, and that gender wage discrimination is not a serious problem? Well, yes and no. Most of the gender wage gap is due to factors other than wage discrimination, so it is illusory as an indicator of wage discrimination. Nonetheless, no study has been able to explain it away entirely.

Even in a world free of all types of gender discrimination, as long as people choose to have children there will likely still be a gap between the average earnings of men and women. Perhaps the gender wage gap is most useful as an indicator of changes in the underlying expectations and social norms that drive men's and women's career and workforce decisions, which themselves may be affected by other types of gender discrimination.

Endnotes

- Most Department of Labor documents define the wage gap in terms of weekly earnings, although sometimes annual earnings are used. A good source for the Department of Labor's data on the gender wage gap is its Fair Pay Clearinghouse at . [back to text]

- Between 1980 and 1997, the percentage of married women with children who were in the labor force rose from 54.1 percent to 71.1 percent. [back to text]

- Unfortunately, the CEA analysis mistakenly applied the Blau and Kahn results to weekly instead of hourly earnings, leading to an inadvertent exaggeration of the extent to which the gender wage gap might be due to wage discrimination. [back to text]

References

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. "Gender Differences in Pay," NBER Working Paper No. 7421 (June 2000).

_________. "Swimming Upstream: Trends in the Gender Wage Differential in the 1980s," Journal of Labor Economics (1997), pp. 1-42.

Council of Economic Advisers. "Explaining Trends in the Gender Wage Gap," CEA White Paper (June 1998).

Furchtgott-Roth, Diana, and Christine Stolba. Women's Figures: The Economic Progress of Women in America. Independent Women's Forum and the American Enterprise Institute, 1996.

Garza, Irasema. Statement Before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, June 22, 2000.

Goldin, Claudia. Understanding the Gender Wage Gap: An economic History of Amerian Women. Oxford University Press, 1990.

U.S. Department of Labor. "Equal Pay: A Thirty-Five Year Perspective," U.S. DOL Women's Bureau Special Report (June 1998).

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us