Revamping Medicaid: A Five-Year Check-up on Tennessee's Experiment

In January 1994, the state of Tennessee, with permission from the federal government, eliminated its traditional Medicaid program and replaced it with a managed care program known as TennCare. TennCare was one of the first projects in the nation to move all Medicaid-eligible people from a typical fee-for-service program into a managed care environment. The proposal for the change came on the heels of years of spiraling Medicaid expenses in Tennessee that would have required either higher taxes or fewer services for the program to remain viable.1

Under TennCare, the state pays a capitation fee—a fixed monthly premium per participant—to a group of privately run managed care organizations (MCOs), which are then required to provide their enrollees with at least the same level of medical services that would have been provided under Medicaid. TennCare would save Tennessee money, advocates argued, because the state would have to pay only the capitation fee—not actual medical expenses—to the MCOs.

Because of these savings, the argument went, the state would also be able to bring under the TennCare umbrella those who previously did not have insurance either because they could not afford it (and were not Medicaid-eligible) or because they had a pre-existing condition that rendered them uninsurable. The original plan was that TennCare would be able to insure about 800,000 or so Medicaid-eligible Tennesseans and another 400,000 uninsured or uninsurable residents. However, now that more than 1.3 million residents (nearly a quarter of Tennessee's population) are enrolled, and the capitation rate has not been adjusted to account for the higher-than-expected risk the program presently faces, TennCare finds itself in somewhat dire financial straits.

A Success Story?

TennCare has succeeded on several fronts, most notably by bringing health insurance to a group of individuals who previously did not or could not otherwise obtain it. By June 1999, TennCare was insuring more than 800,000 Medicaid-eligible people and almost 500,000 uninsured/uninsurable people. Capitation rates are currently about $116 per month per enrollee—a figure that appears to be in line with the original plan's projections. And the MCOs that TennCare contracts with provide their enrollees the same types of coverage—including prescription drugs—that privately funded HMOs do.

The federal government, satisfied with TennCare's overall progress, extended its original five-year waiver by three years, allowing TennCare to operate through Dec. 31, 2001.2 A recent survey of TennCare recipients shows that they, too, are pleased with the program.3 According to the survey, recipients are currently at least as satisfied with TennCare as they were with its Medicaid predecessor. They also now see physicians at their offices more often and visit emergency rooms less frequently for routine care—a severe problem in traditional Medicaid programs.

TennCare has run into problems, however, especially financial ones. Although capitation rates are currently at anticipated levels, they are not, it turns out, enough to cover the costs of the medical care that doctors and hospitals have been providing. In fact, according to a March 1999 audit report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, TennCare pays hospitals about 72 cents for each dollar spent, while doctors receive only 34 cents on the dollar. Moreover, the program's reimbursements to pharmacists are currently the lowest in the nation for a Medicaid program.

The audit report recommends that TennCare increase its capitation payment about 9 percent, or $11 a month per enrollee, to cover current deficits. The report's capitation rate calculation, however, includes $5 from a one-time, $60 million federal government windfall payment—a payment that Tennessee does not expect to receive again in fiscal year 2000. Thus, the increase in the capitation rate should actually be $16, rather than the $11 recommended. Unfortunately, the state's fiscal position is not very sound right now; the budget is in the red.

A Foreseeable Dilemma

So how has TennCare gotten into such poor shape? Simply put, the program has failed to properly pool and price its risk. For starters, TennCare's capitation rates have been calculated solely on the expected medical costs of its Medicaid-eligible participants and not adjusted for the bigger (or smaller) risk other groups might present. The problem was then made worse when TennCare inadvertently changed the risk of the insured pool. As the program's enrollment approached its legislated cap, it was closed to the uninsured—a group that requires few medical services overall—even though it was still admitting the uninsurable—a higher risk group.4

These oversights hurt TennCare because it was not acting as an insurance company should. When an insurance company acts correctly, it is able to collect premiums from all of its enrollees, knowing that only some will actually need coverage at any given time. A health insurance company, for instance, would want to be certain that it insures enough healthy people so that their premiums would help cover the medical costs of its sick enrollees. By properly diversifying its insured pool, an insurance company might collect, say, $1 million a month in premiums, but be required to pay out, perhaps, only $900,000 for health services. If an insurance company were to insure only sick people, though, it would most probably lose money and eventually go out of business.

To build an appropriate pool of participants and properly gauge the pool's risk, a health insurance company must be able to identify the sick from the healthy. Accomplishing this can be tricky, though, because an insurance company has difficulty separating the two groups, even though sick people, who anticipate high medical expenses, are more likely to want to buy health insurance than healthy people. An insurance company therefore needs to find a way around this adverse selection problem. One common way is by insuring inherently diverse groups of individuals—the employees of a firm, for example. The combined risk of diverse groups is almost always lower than that of a given individual, which translates into lower premiums for all.

That said, TennCare, like other state-run insurance programs, is not necessarily able to manage its adverse selection problem since legislation defines the group that the program must insure—namely, Medicaid-eligible people, as well as the uninsured and the uninsurable. It turns out, however, that the mismanagement of the inclusion of these two latter groups is what eventually led to TennCare's current financial difficulties.

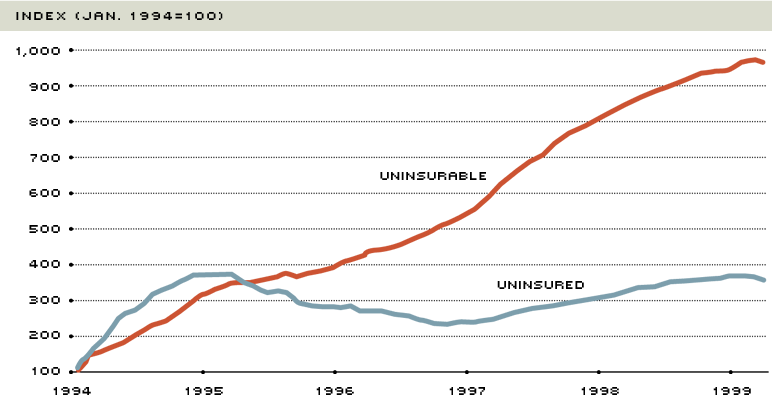

Under the original TennCare framework, the cost of care for the uninsurable was to have been offset by the premiums paid by the uninsured—a healthier group, in general. But as the accompanying chart shows, while the ranks of the uninsured declined, those of the uninsurable—individuals with often costly conditions to treat—continued to grow rapidly. All the while, no necessary adjustments in capitation fees were made. The die of the present crisis, therefore, had already been cast: TennCare's exposure to risk was now greater than had previously been planned for, and the program did not react accordingly.

Prescription for Failure?

Change in TennCare Enrollment by Category

By the spring of 1999, TennCare's enrollment of the uninsurable—people who could not obtain private health insurance because of pre-existing conditions—was about 10 times greater than when the program began in January 1994. Enrollment of the uninsured—a group that requires few medical services overall and that had been shut out of TennCare between 1995-97—was up less than four times its January 1994 level. Thus, relatively more sick than healthy people were entering the program—a potentially dangerous prescription.

SOURCE Budget Office, Bureau of TennCare

A Hard Lesson Learned

At the end of Tennessee's current legislative session—despite the state facing a budget deficit—the Legislature approved an additional $190 million for TennCare in fiscal year 2000. Consequently, the capitation rate is scheduled to increase $16 a month for each enrollee, with MCOs required to spend $12.40 of it on patient care. The Tennessee Legislature and TennCare administration also realize that changes must occur for the program to remain viable over the long run. More-prudent risk management and more flexibility in pricing this risk should hold the program in good stead for some time to come. By the looks of the changes so far, it seems that TennCare has started getting the message.

Endnotes

- See Zaretsky (1995) for more information about the origins of TennCare. [back to text]

- The Health Care Financing Administration—the government agency that administers the Medicaid and Medicare programs—granted Tennessee a five-year waiver in 1993, which allowed the state to withdraw from Medicaid and institute TennCare. Without the extension, the original waiver would have expired on Dec. 31, 1998. [back to text]

- See Lyons and Fox (1999) for more detailed results of the recipient survey. [back to text]

- By federal regulation, TennCare must always cover Medicaid-eligible participants, regardless of the enrollment cap. [back to text]

References

Commins, John. "TennCare Shortfall May Exceed Fears," The Chattanooga Times and Free Press (March 18, 1999).

Kilborn, Peter T. "Tennessee Talks of Retrenchment for Its Health Plan of Last Resort," The New York Times (May 1, 1999).

Lyons, William, and William F. Fox. "The Impact of TennCare: A Survey of Recipients," Center for Business and Economic Research, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (January 1999).

Roman, Leigh Ann. "TennCare: Health Care Providers and the Public Seek Solutions to Save Program," Memphis Business Journal (May 21-27, 1999).

PricewaterhouseCoopers. Actuarial Review of Capitation Rates in the TennCare Program, prepared for the Tennessee Office of the Comptroller (March 1999).

Scott, Jonathan. "TennCare Fine Tuning Expected from Legislature," Nashville Business Journal (March 26-April 1, 1999).

State of Tennessee. Department of Health. TennCare Fact Sheet (July 12, 1999).

________. TennCare Budget Office. Exhibit 5.1: Comparison of Cost—TennCare.

Zaretsky, Adam M. "Revamping Medicaid: One State's Attempt at Reform," The Regional Economist (April 1995), pp, 12-13.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us