Banks Go Shopping for Customers

Acting under intense competitive pressure from other banks and nonbank competitors, a number of U.S. and Eighth District financial institutions have undertaken large-scale efforts over the last decade to reshape their retail branch networks. To maintain profits and market share, these banks have turned increasingly to technology-driven delivery channels, like automated teller and loan machines, fully automated branches, and telephone and online banking. Yet, a growing number of banks are also looking at a less technologically sophisticated channel to help them accomplish their goals: full-service branches in supermarkets and other retail establishments.

Branching Out

Supermarket branches date to the 1960s. Instead of growing into profit centers, however, these outlets generally became mere check-cashing centers. Accordingly, many early branches failed and were subsequently closed. International Banking Technologies, an Atlanta-based supermarket bank consulting group, estimates that only 55 full-service, in-store branches were open in 1971, representing a tiny fraction—less than 1 percent—of the more than 23,000 insured commercial bank branches open at the time.1 By 1985, the number of full-service, in-store branches had inched up to 210—still less than 1 percent of all insured commercial bank branches.

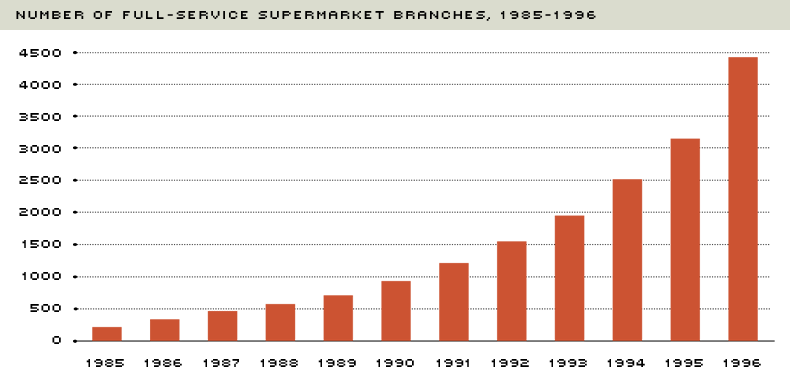

Growth rapidly accelerated in the mid- to late-1980s, however. As the accompanying chart shows, between 1986 and 1996, the number of full-service supermarket branches soared, rising at a compound annual rate of almost 30 percent. Despite showing signs of slowing growth in 1995, the number of these branches surged again in 1996—increasing approximately 40 percent. By 1996, the number of full-service, in-store branches—nearly 4,400—represented almost 7.7 percent of the 57,000 or so commercial bank branches open at the time.

Much of the recent growth in supermarket branches has occurred in the southeastern and western United States, with several large holding companies, such as Wells Fargo and Co., Bank America Corp., and Nations Bank Corp., aggressively entering the field in the 1990s. Wells Fargo, for instance, operated just 37 in-store branches—or 6 percent of its branch network—at the end of 1994.2 By March 31 of this year, the company had 720 in-store branches—some 36 percent of its branch network—up and running.3 Similarly, Nations Bank—a recent entrant into Eighth District banking markets—operated only 18 in-store branches at the end of 1995. The company added 112 branches in 1996 to push its total to 130, and anticipates increasing the number to 330 by the end of this year.4

While Eighth District banks have established in-store branches at a slower pace than those in other parts of the country, a number of major District banks have opened them, including First Tennessee National Corp., Magna Group Inc., Mercantile Bancorporation, and Union Planters Corp. The District is also home to the pioneer of present-day in-store banking—National Commerce Bancorporation. Since opening its first two in-store branches in Memphis in 1985, National Commerce has increased its number of in-store branches to 85, or 84 percent of its branch network.5

Lower Costs

Compared with nonbank competitors like mortgage and consumer finance companies, banks are saddled with an expensive and outmoded retail delivery system.6 To maintain and improve profitability, therefore, many banks have stepped up efforts to cut expenses from their branch delivery systems. Supermarket branches represent one channel through which they can do this.

Banks that have evaluated expansion sites have found that in-store branches are cheaper to construct than traditional bank branches. National Commerce estimates that the typical supermarket branch occupies 400 square feet and costs approximately $200,000 to build and outfit. The typical bank branch, on the other hand, occupies 4,000 square feet and costs roughly $1 million—about five times as much—to build. Moreover, once up and running, the annual operating expenses of a supermarket branch are approximately $350,000, while the annual operating expenses of a conventional branch are typically $700,000 or more.7 With this in mind, a growing number of banks are either shedding traditional branches in favor of supermarket ones or expanding their networks by adding supermarket branches in place of traditional ones.

Greater Convenience

Cost-cutting isn't the only motive for opening supermarket branches, though. It's also a good way for banks to cash in on the trend toward greater customer convenience by enabling shoppers to get their groceries, fill a prescription and make a deposit during the same trip to the supermarket. This represents quite a change from 10 or 20 years ago when customers had to visit their local branch during "banker's hours"—typically 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays. Unlike their traditional counterparts, supermarket branches are usually open six or seven days a week until 7 p.m. or later. They are also typically equipped with one or two ATMs, with some even offering interactive video banking and phone centers. In addition, many provide as wide an array of products and services as conventional branches, including consumer loans, home equity credit lines, annuities, checking accounts, savings accounts and certificates of deposit.8

Let's Make A Deal

Apart from the cost-cutting and convenience-yielding factors, a small but growing number of banks are also looking to supermarket branches to enhance their sales opportunities since supermarkets can give them more frequent and more personal contact with their customers. Supermarket branches can also grant banks ready access to large flows of potential customers; the typical supermarket averages 20,000 to 30,000 customers a week, while the typical bank branch, on the other hand, averages just 2,000 to 4,000 weekly customers.9 In-store branches' nontraditional location also leads to some decidedly unbank-like sales and marketing techniques, such as aisle prospecting, promotional tie-ins and public address announcements.

As barriers to interstate banking and branching have disappeared, banks have also discovered that supermarket branches represent attractive, cost-effective channels of protecting or increasing market share. Having watched larger out-of-state competitors invade their local markets through costly mergers and acquisitions, many smaller banks, which are either unwilling or unable to pay the steep prices of such transactions, have opted instead to establish supermarket branches. To these smaller banks, an in-store branch is a low-cost vehicle through which they can defend their turf.

Small banks are not the only ones discovering the advantages of supermarket branching, however. Many larger banking organizations have found that supermarket branches enable them to increase their market share by attracting their competitors' customers in the supermarket aisles. At the same time, they have also found that a supermarket presence enables them to protect their market share since many institutions sign exclusive contracts with supermarket chains, thereby preventing other banks from competing head-to-head with them in the same marketplace.

Are More "In Store?"

Industry observers expect the number of supermarket branches to increase over the next several years as banks continue efforts to replace an outdated retail delivery system with one that is more cost-effective and accessible to customers. In fact, several major players in the banking industry have recently incorporated supermarket branches into their restructuring efforts. Cleveland-based National City Corp., for example, announced plans this past August to close or reconfigure 200 of its traditional branches by replacing them with 110 scaled-back supermarket branches and 60 full-service supermarket branches.10 The duration of the trend, however, depends in large part on how fast the banking and supermarket industries consolidate. Once the bulk of the pairings between banks and grocery chains have taken place, growth will slow considerably. In the meantime, bank customers will increasingly find that they can manage their finances and fill their freezers in one stop.

Endnotes

- Data on insured commercial bank branches comes from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. [back to text]

- See Crockett (1996). [back to text]

- The March 31 figure comes from a company fact sheet. [back to text]

- These figures came from the company's 1996 annual report. [back to text]

- The updated figure was obtained from the company's 1996 annual report. [back to text]

- Radecki, Wenninger and Orlow (1996) discuss some of the cost disadvantages under which banks operate. [back to text]

- See Radecki, Wenninger and Orlow (1996). [back to text]

- Certain products and services, like mortgage loans, safe deposit boxes and investment products, are sometimes limited to traditional bank branches. See Wilson (1997). [back to text]

- This information is provided by National Commerce Bank Services, which is a subsidiary of National Commerce Bancorporation. [back to text]

- The company also expects to close or sell 30 branches. See Chase (1997). [back to text]

References

Crockett, Barton. "2 in the Aisles: Wells, B of A Slug It Out In-Store," American Banker (February 9,1996), p. 4.

Chase, Brett. "National City to Shut Down or Revamp 200 Branches," American Banker (August 25, 1997), p. 4.

Radecki, Lawrence J., John Wenninger, and Daniel K. Orlow. "Bank Branches in Supermarkets," Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York (December 1996).

Wilson, Caroline. "Retail-Oriented Supermarket Branches," America's Community Banker (May 1997), pp. 16-20.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us