A Recipe for Monetary Policy Credibility

Recent economic research suggests that monetary policy will be more effective if it is both transparent and credible. A transparent monetary policy is one in which the central bank clearly states its commitment to some goal—in this case achieving price stability—and how it intends to get there. Credibility is attained when the central bank's actions are consistent with reaching this goal. For the Federal Reserve, the goal is a sustained, low inflation rate.

But a low inflation rate does not necessarily guarantee a credible monetary policy, for straightforward reasons: If financial markets are unsure of the Federal Reserve's commitment to keeping inflation in check, then the Fed's credibility with them will be suspect. Many economists believe that one way the Fed, or any central bank, can enhance its credibility is with a transparent policy rule that is deliberately designed to achieve long-term price stability.

A Monetary Insurance Policy

Although it is difficult to measure precisely, a credible monetary policy could be summed up in the following phrase: Policymakers must always say what they mean and mean what they say. Three ingredients are crucial in this respect. The first is a stated commitment to achieving a given policy goal. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan does this by reiterating that the Fed's ultimate goal should be long-term price stability, of which the benefits are many and varied.1 The second ingredient is a recognition that there are limits as to what monetary policy can and cannot accomplish. From this, two points follow: First, the only variable the Fed can reliably control over a long time period is the money supply, which is the major factor that determines the inflation rate; and second, because there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run, an economy with a low inflation rate is preferable to one with a high inflation rate.2

The final ingredient that goes into a credible monetary policy is a well-defined plan—announced beforehand—which stipulates how the Fed intends to achieve and maintain its stated goal of long-run price stability. This last feature recognizes that the best monetary policy is a transparent one which—because it is well publicized and well understood—creates the least uncertainty in financial markets.

The goal of the Federal Reserve's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is to keep inflationary expectations from worsening. If the committee fails to do so, uncertainty will creep into financial markets. For example, suppose that an acceleration in the current inflation rate occurs, but—because Fed policymakers perceive the movement to be temporary—they take no restraining action. If this decision is viewed positively by financial market participants, they will be less apprehensive about the increase in inflation. If financial markets are not convinced of this, and expect instead a permanent increase in the inflation rate to result from the Fed's inaction, they will react in a manner that increases financial market volatility. Accordingly, the heightened inflationary expectations—which arise from less confidence in the Fed's ability to curtail future inflation—could cause a rise in long-term interest rates, since there will now be more risk associated with holding fixed-income securities (bonds). Thus, a credible monetary policy tends also to yield low and stable nominal interest rates.

Are Policy Rules Needed?

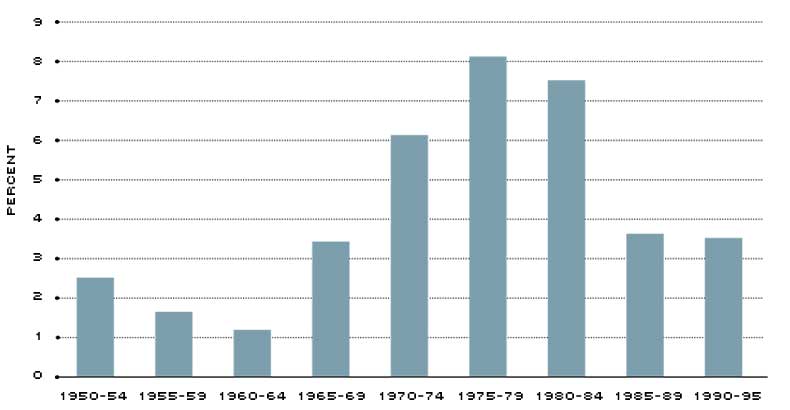

Given the relatively low inflation rate that has persisted over the past four and a half years, some economists and policymakers maintain that the Federal Reserve has finally achieved its long-sought-after goal of full credibility. This environment stands in stark contrast to the 1960s and 1970s, when monetary policymakers seemed more committed to keeping unemployment from accelerating than to achieving long-term price stability. This stance largely reflected the view, which was commonly held at the time, that there was an inflation-output trade off that policymakers could reliably exploit. The result, as shown in the figure, was a substantially higher average inflation rate during the 1970s than during the previous two decades.

Many economists have since argued that the best way to prevent a repeat of the substandard inflation performance of the late 1960s to early 1980s is through an arrangement that consistently strives to achieve the goal of long-run price stability.

One recent tactic that has been taken along these lines is to announce fixed inflation targets, which has been done by the central banks of Canada, England and New Zealand. Some have proposed that the Fed go a step further by adopting a policy that would more explicitly bind policymakers. Several types of these rules have been advocated.

Probably the best-known rule is the one advanced by Milton Friedman, which calls on the Fed to increase the growth of the money stock at a known, fixed rate. However, changes in the financial structure of the economy since the early 1980s have made the reliability of this rule questionable. Three other popular policy rules that have been proposed in recent years and are, therefore, perhaps more reliable are: the "McCallum rule," the "Taylor rule" and the "Svensson rule."

Essentially, the McCallum Rule, proposed by Carnegie-Mellon professor Bennett McCallum, states that the FOMC should specify a target growth rate for nominal GDP (the current dollar value of final goods and services produced) since it is the product of two components: price and quantity. By targeting nominal GDP, the Fed can, therefore, implicitly target the prevailing inflation rate.

By contrast, the Taylor rule, named after Stanford University professor John Taylor, stipulates that the FOMC should raise or lower the federal funds rate in response to how real GDP and inflation are behaving relative to two benchmark measures. For example, the rule says that the Fed should attempt to push up the federal funds rate through open market operations if the prevailing inflation rate is above a specific target rate set by the Fed. Similar restraint would be needed if real GDP is greater than potential GDP.3

The third rule, which is advocated by Swedish economist Lars Svensson, is a variation of targeting inflation. Under this rule, the Fed's short-run (or intermediate) inflation target is the inflation rate that is forecasted to prevail two years hence. By continually setting policy that is tied to a two-year-ahead inflation forecast, the Fed can deliberately bring about its long-run goal of price stability.

Are Rules Better Than Discretion?

Few economists would quibble with the notion that some discretion is appropriate when setting monetary policy. After all, economic events seldom transpire exactly as predicted. For this reason, some believe that any sort of a fixed rule is inferior to a discretionary framework because it locks policymakers in a box. But policy rules have several advantages over discretion. First, because financial markets tend to be forward-looking in their behavior, a rule that is also forward-looking would tend to reduce the uncertainty associated with future policy actions. A stated policy rule would also hold the monetary authority more accountable for its actions, making it easier to evaluate policy outcomes. Finally, a framework that allows policymakers to adjust policy in response to every wiggle in the economic data (discretion) could lead to a more erratic monetary policy. At the same time, because policy rules must be developed on the basis of past historical economic relationships, which do not always hold, they can break down over time.

Whichever side one takes in the rules vs. discretion debate, one thing is clear: To ensure economic stability, monetary policy must be implemented in a forward-looking fashion. In other words, policymakers must consider how their actions will affect both the current and future inflation rates. In this vein, policy rules enhance the credibility of monetary policy by increasing accountability and improving the transparency of policy actions with the public and financial markets. Without some form of a rule, monetary policy could be significantly influenced by personalities or unpredictable economic events.

Endnotes

- See Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (1994). [back to text]

- This means that a higher average inflation rate over a long horizon will not translate into a lower average unemployment rate, and vice versa. [back to text]

- The economy's potential growth is usually defined as the rate of growth that is possible given the existing supply of labor, capital, technology and natural resources. It can also be influenced by the existing regulatory and tax structure. In the Taylor model, inflation begins to accelerate if real GDP rises above potential GDP. [back to text]

References

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "A Price Level Objective for Monetary Policy," 1994 Annual Report.

Friedman, Milton. "The Role of Monetary Policy," The American Economic Review (March 1968), pp. 1-17.

McCallum, Bennett. "Robustness Properties of a Rule for Monetary Policy," Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, No. 29 (1988), pp. 173-204.

Svensson, Lars E. "Comment on John B. Taylor, 'How Should Monetary Policy Respond to Shocks while Maintaining Long-Run Price Stability,' " Achieving Price Stability, a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 29-31, 1996.

Taylor, John B. "Policy Rules as a Means to a More Effective Monetary Policy," Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan, Discussion Paper 96-E-12 (March 1996).

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us