District Economic Update: Will the Sailing Remain Smooth?

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, output of final goods and services produced (gross domestic product) rose at a 3.8 percent annual rate in the second quarter, substantially above its long-term trend growth rate of 2.8 percent. Moreover, nearly 5.5 million jobs have been created since July 1991, the official end of the last recession.

The Eighth District economy has also prospered recently: the District unemployment rate measured 5.4 percent in July, almost 1 percentage point lower than a year earlier and considerably lower than the 6.1 percent rate for the entire U.S. If the current expansion continues unabated, it will equal the nation's post-World War II average duration of 50 months by this time next year. Because what happens nationally is generally an important barometer for economic developments at the state level, this news, one would think, bodes well for Eighth District states. Should we be so optimistic? Can we expect the District economy to continue to mirror the performance of the national economy?

Composition of the District Economy

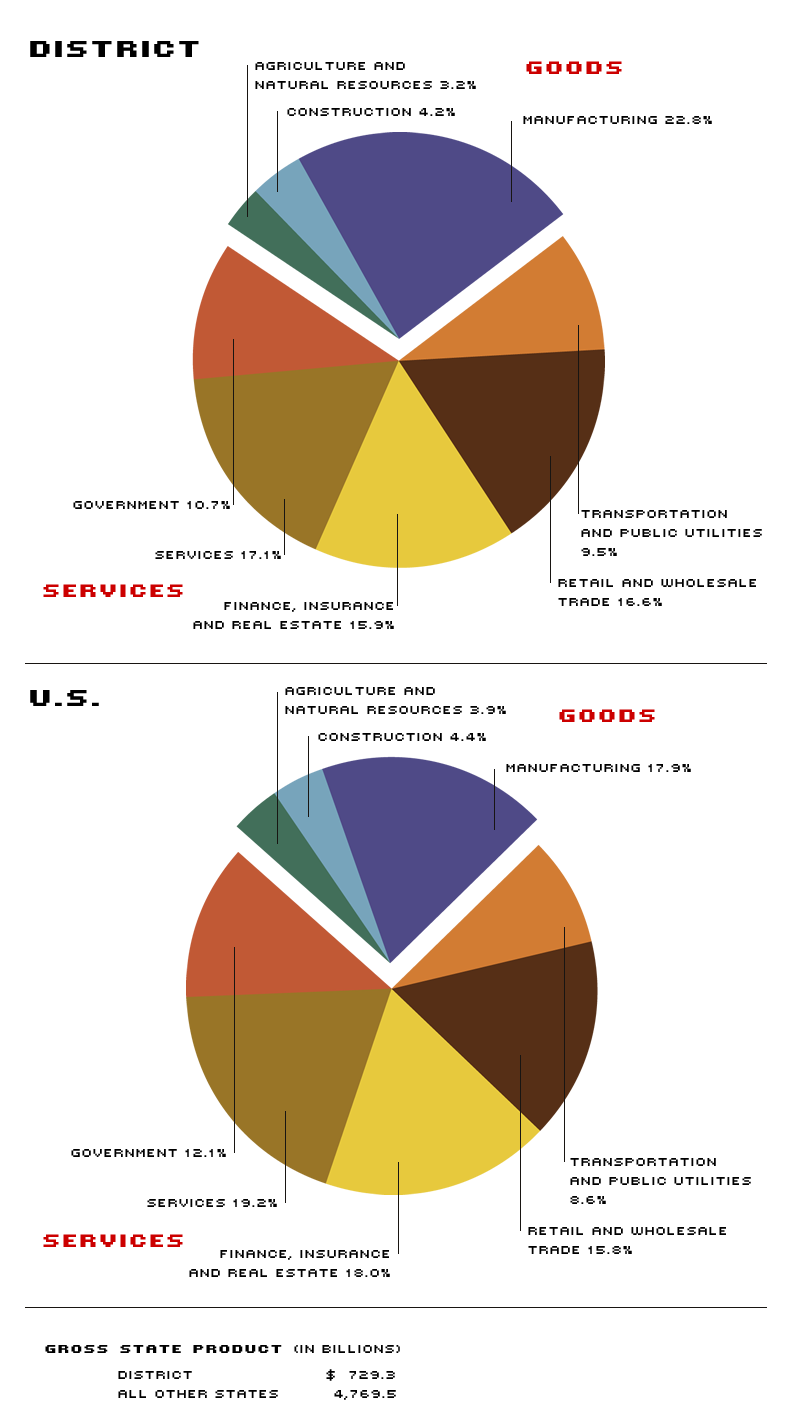

In 1990, the latest data available, the output of final goods and services—termed gross state product (GSP)—in the seven states of the Eighth Federal Reserve District totaled $729.3 billion (see pie charts).1 With output in all other states at just under $4.8 trillion, District output, broadly defined, was about 13.3 percent of the national total.2

The District economy, while diversified, is more manufacturing-intensive than the rest of the country. Manufacturing output, totaling nearly $167 billion in 1990, was almost 23 percent of GSP. In contrast, manufacturing output in all other states was only 17.9 percent of GSP. Indiana and Kentucky, both with important durable goods-producing industries like autos and household appliances, are the most manufacturing-intensive of the seven states, with Illinois the least manufacturing-intensive.

Like the U.S., the District has basically a service-based, or nonmanufacturing, economy, providing the services of everything from doctors and computer programmers to secretaries and teachers. But while nonmanufacturing output makes up nearly 70 percent of District GSP, that was somewhat less than the 74 percent for the rest of the United States. In particular, the financial services and government sectors do not have as strong a presence in our seven-state economy as they do in the rest of the country. On the other hand, retail and wholesale trade and transportation and public utilities are relatively more important to the District economy.

Industry Employment Trends

Because output data at the state level are computed with a substantial time lag, economists must look at other indicators to get a more up-to-date portrait of a state's economic well being. One important statewide indicator is payroll employment growth. In general, if an industry is expanding (if the level of output is increasing), employment will usually rise—at least in the short run. Over a longer horizon, this need not be the case. For example, the percentage of workers in the automobile manufacturing sector has declined steadily over time even as auto production increased. Why? Because technological gains over the years have enhanced worker productivity: it takes fewer workers today to build an automobile than it did, say, 25 years ago.

The data tables in this publication report nonagricultural (excluding agriculture and natural resources) payroll employment growth for the United States and each of the seven District states by industry. As is evident from these pages, U.S. payroll employment growth was quite strong in the second quarter, expanding at a 3.7 percent annual rate. This gain was up substantially from the 2.2 percent rate of gain in the previous quarter and was the fastest rate of growth since late 1987. More important, the sectoral gains were rather broad-based, occurring in construction (12.6 percent rate), services (6.1 percent rate) and wholesale and retail trade (4 percent rate). Even manufacturing employment rebounded in the second quarter (up at a 1.1 percent annual rate), after falling throughout most of 1993.

In the District, on the other hand, payroll employment growth appears to have ebbed over the past two quarters. After registering a robust 3.1 percent growth rate in fourth quarter 1993, payroll employment growth has slowed from a 1.9 percent annual rate in the first quarter to a 1.5 percent annual rate in the second quarter, its slowest pace since early 1992. With declines in manufacturing employment in Illinois, Mississippi and Missouri, District goods-producing employment (manufacturing and construction) retreated considerably from its strong pace in the first quarter, falling at a 0.4 percent annual rate—the first decline in more than two years. By contrast, goods-producing employment growth remained strong in Arkansas.

Some modest slowing was also evident in District service-producing industries. Since fourth quarter 1993, when employment in service-producing industries rose at a 3.6 percent rate, employment growth has slowed markedly, falling to a 2.4 percent rate of increase in I/1994 and to a 1.4 percent rate of increase registered in II/1994. Some of this slowing can be attributed to the Teamsters strike this past April, which caused temporary employment declines in the transportation and public utilities sector. In general, though, slow or slowing employment growth is evident in other service-producing sectors, like finance and real estate and wholesale and retail trade.

Perhaps this pattern of moderating employment growth over the past two quarters is a transitory development, given the high degree of volatility of state employment data. For example, measured on a four-quarter basis (II/93 to II/94), District payroll employment growth has remained at 2 percent or more for seven consecutive quarters. On the other hand, while year-over-year payroll employment growth has increased for nine consecutive quarters for the United States, it has declined slightly for two consecutive quarters for the District. By no means an ominous development, this slowing does bear watching.

Other Indicators

Additional indicators can give us a clearer picture of the District's economic well being. One such indicator is the number of business failures. One can perhaps view business failures as a lagging indicator because they typically pick up after the onset of slow growth, not before. By this rule of thumb, the District economy still appears to be expanding: the number of business failures in the District declined 3.6 percent in the second quarter this year to 1,468, following a 1.6 percent rise in the first quarter. State by state, the number of business failures shows a mixed pattern. The number of business failures have increased for two consecutive quarters in Arkansas and Kentucky, but have fallen for three consecutive quarters in Illinois and four consecutive quarters in Indiana. Measured from four quarters earlier, though, District business failures are off 17.2 percent and are down in all states except Arkansas.

Although just over 4 percent of total District output, the construction industry is sometimes viewed as a bellwether for future economic growth. If true, then we perhaps should be concerned about our future prospects. Construction employment growth was flat in the second quarter, after rising strongly over the previous two quarters. District housing starts in the second quarter totaled nearly 194,000 (annualized), down 7.8 percent from their first-quarter average of just over 210,000 and down 12.6 percent from the nearly 222,000 in fourth quarter 1993. Housing starts in the second quarter were off from their first-quarter level in all states except Kentucky and Tennessee, where they rose 9.4 percent and 1.7 percent, respectively, and remain below their fourth quarter 1993 levels in all states except in Arkansas.

A final indicator is retail sales (for example, sales of clothing, food and automobiles). Because consumer spending is the largest sector of the economy, the retail sales sector is watched closely. In the second quarter this year, District retail sales rose at a 1.7 percent annual rate, following a 3.3 percent annual rate of increase in the first quarter.3 Over the past two quarters, retail sales have risen at a 0.2 percent rate in Illinois, a 0.7 percent rate in Indiana, a 1.8 percent rate in Missouri and a 10.7 percent rate in Tennessee. When inflation is factored in, however, retail sales have actually declined in three of the four District states over the past two quarters. Nevertheless, measured from four quarters earlier, retail sales are up 6 percent for the four states.

One important caveat: trends at the state level are sometimes hard to gauge in as short a time as a few quarters. Thus, the weakness that is apparent in some indicators over the past two quarters may be temporary. A strengthening U.S. economy, along with a rebounding world economy, could perhaps reverse these trends. Further, state data is exceedingly volatile and subject to considerable revision. As a result, only time will tell whether this pattern is real or simply a statistical anomaly.

Endnotes

- The seven-state area comprises Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. [back to text]

- This share has fallen over time. In 1980, District output measured 16.5 percent of all other U.S. output; in 1985, this share fell to 15.6 percent. [back to text]

- Retail sales only includes data from Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Tennessee, and it is not adjusted for inflation. [back to text]

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us