After the 500-Year Flood: An Early Look at the Return to Normalcy

"The costliest natural disaster in history" is how some have described the flooding of the upper Mississippi Valley this year. At this writing, it is still too early to validate this supposition. And although the water has receded below flood stage in many parts, forecasts of continuing rain cast doubt as to when the Midwest will fully dry out.

This flood has been dubbed a "500-year flood," not because it happens every 500 years, but because the chance of a flood of this magnitude occurring in any year is approximately one in 500. It is thus quite conceivable, although highly unlikely, that this could occur again next year.

Determining the total damage wrought by the flood will take some time: The water must recede enough to allow people to return to their homes and businesses before they can assess the damages. An eventual return to normalcy will require rebuilding what, for the most part, are uninsured losses. Government assistance through emergency programs is available, but such assistance is mostly through loans that usually do not cover all of the loss. In some cases, buyouts at pre-flood market values were offered to those with flood insurance and extensively damaged homes. Some without flood insurance have received some payment from their local governments, but these amounts have usually been nominal. In either case, transfer of the property's title to the government was usually a necessary condition for the payment.

Different estimates of the total damage have been floated, many based on assumptions that cannot easily be verified. In some respects, it is not difficult to claim that this natural disaster could be the costliest in history since damages are measured in current rather than inflation-adjusted dollars. One should therefore be careful to account for inflation when comparing a disaster in one year with a disaster in a prior year. Nonetheless, damage assessments for the flood that were current as of this writing indicate that final losses could reach historic proportions.

Some Preliminary Numbers

In early August, the State Emergency Management Agencies (SEMA) in Missouri and Illinois had estimated damages for their states of $2.7 billion and $930 million, respectively. These figures included damage to agriculture (more than one-half the totals), infrastructure, private housing and additional unemployment insurance claims. In Missouri, SEMA estimated that about 3,200 businesses suffered physical damage and that bridges, roadways and other public facilities suffered more than $120 million in damage. This public facilities figure, however, did not include any damage to Jackson County (Kansas City), St. Louis City or St. Louis County. In Illinois, most of the $930 million was divided between crop losses ($565 million) and infrastructure ($258 million), with the remainder for housing and unemployment.

The Army Corps of Engineers, a federal agency, estimated damages between $2.5 billion and $3 billion for its St. Louis District.1 This figure was attributable primarily to infrastructure damage, much of which will not become apparent until winter approaches and roadways begin to freeze and thaw. Even at this writing, though, the estimates from these three agencies were understated because they did not include the damage that occurred when the Monarch Levee in the western part of St. Louis County broke. This breach flooded many industrial parks, affecting about 300 businesses, closed the second-busiest airport in Missouri and forced the evacuation of a county jail. Early damage estimates were between $150 million and $200 million for this area alone. The appraised value of this flooded real estate, excluding personal property and exempt property such as the airport and jail, equals 65 percent of the total appraised value for all flooded land in St. Louis County. Accounting for this additional damage, the St. Louis Fed's estimate for total damage to Missouri and Illinois, at this writing, was between $2 billion and $3 billion.

The Accuracy of Early Estimates

To add perspective to these figures, a comparison with the 1973 flood is in order. Accurate damage figures for the 1973 flood are available, and they demonstrate well the difficulty in estimating final damages before complete assessments can be made.

In 1993 dollars (calculated using a GDP deflator), the initial estimate for damages from the 1973 flood in Missouri was $358 million. Missouri's final damage assessment was $396.91 million. This estimate was off by 11 percent. In Illinois, the initial damage estimate, in 1993 dollars, was $257.1 million, and the final figure was $768.29 million. This estimate was off by a whopping 199 percent. As it turned out, of the 16 states reporting damage in the 1973 flood, Illinois recorded the second-largest loss after Louisiana.2 In the more recent flood, Missouri's losses look to be the largest of the nine states reporting losses.3

Of course, the comparison between the two floods is not perfect. The 1973 flood was concentrated in the lower rather than the upper Mississippi Valley, it happened in the spring rather than in the summer, and its magnitude was much smaller than that of the recent flood. What's more, the 1973 flood lasted about one week, while the recent flood has lasted more than two months. Thus, many of the flooded structures have been submerged longer than ever before, leaving to speculation the extent of the water's destructive ability.

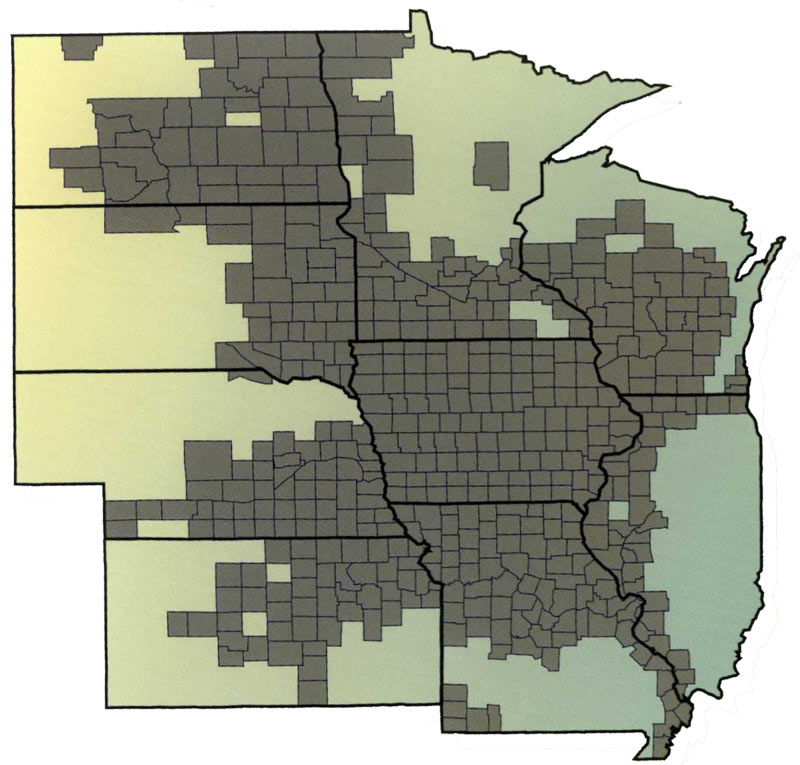

Counties Declared Federal Disaster Areas (as of August 20, 1993)

Counties in nine states were declared disaster areas. Of these, only Missouri and Illinois are in the Eighth Federal Reserve District

The Effects on Agriculture, Business and Banking

In addition to figures for total damage, estimates for the amount of acreage damaged by this year's flooding were also reported. According to the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) in Missouri, about three million acres were damaged by flooding. This damage figure represents approximately 7 percent of Missouri's land mass. The ASCS in Illinois reported that about 874,000 acres were damaged by flooding, approximately 2.5 percent of Illinois' land mass. Most of the acreage in both states is used for corn and soybean production.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, in its September Crop Production Highlights report, projected corn production in Missouri and Illinois to be lower for this year than last: Missouri's corn production in 1993 is projected to be 42 percent less than 1992's crop and 11 percent less than 1991's. Interestingly, Illinois' 1993 corn production forecast is for a crop 15 percent smaller than last year's, but 19 percent larger than 199l's crop. The forecasts for soybeans follow a similar pattern: In Missouri, 1993's output should be 22 percent less than 1992's and 7 percent less than 199l's; in Illinois, this year's soybean output should be 6 percent less than last year's but still 12 percent more than 1991's.

In industrial areas, many businesses had to suspend operations because of direct flooding in their facilities or transportation troubles related to the flooding. These suspensions affected numerous employees who were shut out of their workplaces. According to the Missouri Department of Employment Security, about 31,500 workers statewide were displaced at the peak of the crisis because of flooding. As of mid-August, approximately 11,000 were still out of work. The flooding also increased applications for unemployment insurance benefits by 10,900. Illinois reported about 500 nonagricultural workers displaced because of flooding,with about 200 still out of work by late August. This figure did not include workers who were shut out of their workplaces but still received vacation pay and were therefore considered still employed.

A survey of Eighth District banks in the affected areas revealed that operations continued as usual in most cases. Some banks did have to move their operations to different locations, but were able to conduct their normal daily business with minimal inconvenience. About 10 percent of the surveyed banks reported significant (more than 10 percent) effects on their portfolios, mostly because of agricultural loans.4

In mid-August, predictions were that regular traffic would resume along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers by mid-September at the earliest. In late August, the Missouri River was reopened, and trial barge movements along the Mississippi River had begun. Before the Mississippi reopens fully, however, the Coast Guard will probably have to rechart it to determine how the channel might have shifted below the swiftly moving water. Delays in reopening the river will most likely translate into greater strain on the alternative transportation systems, especially trucking, and higher transportation costs for firms. Nevertheless, once the river is reopened, regular flows of goods will resume, bringing us one step closer to normalcy.

Endnotes

- The St. Louis District comprises those counties on the Missouri and Illinois sides of the Mississippi River from Cairo, Ill., north to Quincy, Ill., including the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. It does not include the areas surrounding the Missouri River. In some cases, the district is more than 200 miles wide. [back to text]

- The 16 states were Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. [back to text]

- The nine states were Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. [back to text]

- The survey excluded banks from St. Louis City and St. Louis County. [back to text]

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us