Multinationals from Emerging Economies: Growing but Little Understood

Multinational companies from the emerging world are a relatively new phenomenon. A decade ago, 20 companies on the Fortune Global 500 list were based in emerging economies; three years ago, 70 were. In all, emerging economies are home to an estimated 21,500 multinationals.

Emerging Markets Multinationals (EM-MNCs) have become important in almost every industry. India's Infosys and TCS have become two of the world's leading information technology companies. China's Haier is the fourth-largest maker of home appliances in the world, and its ZTE is on its way to becoming one of the world's top five manufacturers of telecommunications equipment and systems.

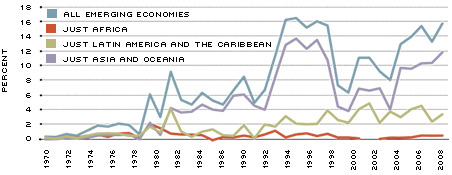

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), multinationals in emerging economies accounted for only 0.4 percent of world outward foreign direct investment (FDI) in 1970. That share grew to 15.8 percent by 2008. Figure 1 illustrates the growth in outward FDI from emerging economies. Alone, emerging nations in Asia and Oceania accounted for 11.9 percent of world outward FDI in 2008; among these nations, China has seen the most dramatic and continuous growth.1

Emerging Economies' Share of Global Foreign Direct Investment Outflows

SOURCE: Authors' calculations based on data from the UNCTAD.

Click to enlarge

Economists are studying these firms in order to understand the business philosophies that could have led to such growth trajectories and the possible impact their presence will have on the international economy.2

How Multinationals Start

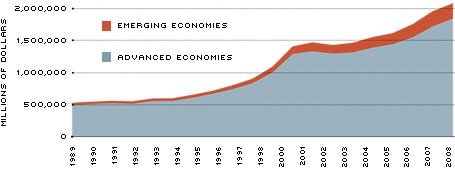

Firms tend to locate where barriers are easier to overcome. For firms in emerging countries, this initially meant locating in nearby countries with regional, cultural or language ties (so-called South-South FDI). This trend seems to be changing, however, as firms from emerging economies gain prominence: Not only has the share of FDI from the emerging world grown over time, but so has the amount of FDI from the emerging world that is directed into advanced countries (so-called South-North FDI). Figure 2 illustrates the change in the amount of FDI invested in the United States from emerging economies and advanced economies. In 1989, FDI from emerging economies made up 7.2 percent of the total amount of FDI invested in the United States. By 2007, that share had grown to 12.1 percent.3

Figure 2

Distribution of FDI into the United States, 1989-2008

SOURCE: Authors' calculations based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data are normalized and represent the position on a historical-cost basis.

Click to enlarge [back to text]

Why Become Multinational?

The traditional explanation for multinational activity is a version of a theory called "the O.L.I. paradigm." Multinationals exploit three sets of advantages: (1) Ownership advantages encompass the development and ownership of proprietary technology or widely recognized brands that other competitors cannot use. Empirical analysis shows that multinationals are often technological leaders that invest heavily in developing new products, processes and brands, which are then kept confidential and are protected by intellectual property rights. (2) Localization advantages refer to the benefits that come from locating near the final buyers or closer to more abundant and cheaper production factors, such as expert engineering or raw materials (important to agrifood multinationals, for example). (3) Finally, multinationals internalize the benefits from owning a particular technology, brand, expertise or patent that they find too risky or unprofitable to rent or license to other firms due to the difficulties of enforcing international contracts.

Still a Black Box

These explanations of multinational activity apply in the case of multinationals from advanced economies, but are less likely to explain the recent trend of multinationals from emerging countries. The 2006 World Investment Report by the UNCTAD shows that firms from emerging countries are very heterogeneous in terms of their origin, maturity, position in the value chain and strategy. This suggests a variety of drivers for internationalization. Such huge heterogeneity makes it difficult to generalize about how EM-MNCs are similar or dissimilar to more traditional multinationals. In fact, there are essentially no theories; the little empirical research available consists mostly of case studies.

EM-MNCs do not usually possess strong global brands or cutting-edge technologies

that place them close to the technology frontier.4 Rather, they often acquire established brands to become well-known—such as the Tata Group of India, which acquired the automobile manufacturers Jaguar and Land Rover—or acquire firms that already developed proprietary technology.

However, this does not mean that they do not possess ownership advantages. One view is that EM-MNCs expand to other countries in order to obtain new advantages to serve as a further springboard for internationalization. One of these advantages is the ability to adapt products developed elsewhere to domestic markets, gaining greater production efficiency by using inputs more efficiently or by using more labor and less capital, or by reducing overhead costs. Some EM-MNCs have advantageous access to resources and markets, and also have "adversity advantages," that is, the ability to survive poor infrastructure, corrupt bureaucracies, regulatory uncertainties and weak educational institutions—all of which hamper multinationals from advanced economies that operate within emerging economies.

Consequences for Developed Countries

Evaluating the consequences for developed countries is difficult because data are very limited, which makes empirical research challenging. The immediate effect of entry in advanced economies is the introduction of greater competition in input and product markets. Because many EM-MNCs are active in mature products industries, they could encourage less dynamic sectors to become more innovative within host economies and could introduce a reallocation of resources, such as capital and labor, from less efficient to more efficient firms. Consider, for example, the "white goods" industry. Haier, which is partly owned by the Chinese government, opened a factory in South Carolina in 1999, shook up the dormitory refrigerator industry with new types of refrigerators and then expanded into other niches.

If EM-MNCs expand their production into advanced economies by opening new plants or expanding old ones, they may contribute positively to the host country's employment situation. The Haier web site says that more than 95 percent of Haier America's employees in the U.S. are Americans.

Finally, the regulatory frameworks that allow FDI into advanced economies may need revisions in order to balance the protection of national interests, such as national security, defense and access to key resources, without alienating foreign companies.5

Endnotes

- The reader should be careful when considering outward FDI statistics of certain countries. According to UNCTAD, emerging market statistics on FDI may be biased due to an issue of "round-tripping," which can inflate FDI flows. Round-tripping is caused by differential treatment of foreign and domestic investors, which could lead to double counting of funds by allowing a country to both channel funds out of and into the country through FDI. [back to text]

- International business scholar Ravi Ramamurti points out that it took many years of research to identify firm-specific advantages of Western multinationals. Understanding the advantages and effects of emerging market multinationals may take just as long. [back to text]

- Calculated based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis' Country of Ultimate Beneficial Owner tables. See www.bea.gov/international/di1fdibal.htm [back to text]

- One such exception is Brazil's Petrobras, which is the world leader in the development of advanced technology from deep-water and ultra-deep water oil production. [back to text]

- One example of such changes in the U.S. is the latest installment of FDI regulation, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007, which establishes a framework for the review of foreign acquisitions of U.S. assets by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). The reform of the CFIUS had gained impetus after the sale of port management businesses in six major U.S. seaports to a company based in the United Arab Emirates. [back to text]

References

Aykut, Dilek; and Goldstein, Andrea. "Developing Country Multinationals: South-South Investment Comes of Age." Working Paper No. 257, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, December 2006.

Goldstein, Andrea. Multinational Companies from Emerging Economies: Composition, Conceptualization and Direction in the Global Economy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Goldstein, Andrea; and Pusterla, Fazia. "Emerging Economies' Multinationals: General Features and Specificities of the Brazilian and Chinese Cases." Working Paper No. 223, CESPRI (Centro di Ricerca sui Processi di Innovazione e Internazionalizzazione), October 2008.

Luo, Yadong; and Tung, Rosalie L. "International Expansion of Emerging Market Enterprises: A Springboard Perspective." Journal of International Business Studies, July 2007,

Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 481-98.

Ramamurti, Ravi. "What Have We Learned About Emerging-Market MNEs? Insights from a Multi-Country Research Project." Presented at the Copenhagen Business School conference Emerging Multinationals: Outward FDI from Emerging and Developing Economies, Copenhagen, Denmark, Oct. 9-10, 2008.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. "Rising FDI into China: The Facts behind the Numbers," 2007.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. "World Investment Report," 2006.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us