Laissez le Bon Temps Roulette: Letting the Good Times Roll on Riverboat Casinos

Until 1990, casino gambling was legal only in Nevada and Atlantic City, N.J. Since then, it has been authorized in 23 states, including four in the Eighth Federal Reserve District. In a quest to raise revenues without imposing additional taxes on the populace, these states have approved casino gambling, touting that new jobs will be created and additional monies will be made available for education.

Iowa, which was the first Midwestern state to approve riverboat gambling, found it to be quite successful. Illinois, Missouri, Indiana and Mississippi have now followed Iowa's lead and passed riverboat gambling initiatives. The degree of success of these operations varies by state and depends on the concentration of nearby competition. Because gambling is too new in Indiana and Missouri, riverboats in Illinois and Mississippi are the centerpieces for our District. Arkansas, Kentucky and Tennessee have not yet tackled the issue, either in an election or in the legislature.

Illinois

Illinois' first boat opened in September 1991. During its first week of operation, which was only five days long, 7,130 people attended, and adjusted gross receipts—after payouts for winnings—were about $296,000. Of this total, about $73,500 was paid in state and local taxes: Illinois requires two dollars of the admission fee go to the state and locality (one dollar to each) and imposes a wagering tax—15 percent to the state, 5 percent to the locality—on the adjusted gross receipts.

At the end of 1991, with two riverboats operating, adjusted gross revenues in Illinois were almost $15 million, with more than $3.5 million in taxes going to government agencies. By 1993, Illinois had 10 riverboats, with revenues of almost $606 million. During the first quarter of 1994, 12 riverboats produced revenues of slightly more than $217 million, about $10 million less than receipts for all of 1992, and logged more than four million visitors. If attendance and revenues continue on this path for the remainder of the year, the state can expect to collect wagering taxes of almost $175 million and admissions taxes of about $34 million.

Illinois law does not allow dockside gambling, unless circumstances prevent the boats from cruising, nor does it include a loss-limit—the maximum amount an individual can lose during a gambling excursion. This certainly gives its casinos an advantage over those that are subject to a loss-limit in neighboring states, like Missouri.

Missouri

Voters approved Missouri's riverboat gambling referendum in November 1992, and plans were immediately hatched to place riverboats in the St. Louis and Kansas City metropolitan areas. Opponents of gambling, however, filed suit, questioning whether games of chance—slot machines, craps, roulette, etc.—were constitutional in the state. The state Supreme Court said no, thereby requiring a constitutional amendment to allow such games on the boats. In April 1994, the amendment failed by the narrowest margin in state history. A recount was requested by the pro-gambling campaign, but the outcome was a wider margin of defeat for the amendment. In response, the state legislature legally redefined games of skill to include craps, video poker and video blackjack. This law is expected to face a court challenge, but, until then, riverboats have opened to offer games of skill.

Missouri imposes admission and wagering taxes similar to Illinois'. The state receives 18 percent and the locality receives 2 percent of adjusted gross revenues; two dollars of the admission fee are turned over to the state gaming commission, which keeps one and gives one to the locality. Also like Illinois, Missouri does not allow dockside gambling.1 It does, however, impose a loss-limit of $500 per excursion on individuals. This provision superficially appears to handicap Missouri casinos against their counterparts in neighboring states where loss-limits do not exist. The provision's effectiveness is blunted, though, because it applies only to a single excursion: Individuals need only pay an additional admission fee for further excursions to continue playing. What this will mean for revenues remains to be seen, particularly because many of the plans, especially in St. Louis, call for extensive land-based building—for example, hotels—in conjunction with the riverboats, which will raise other revenues for the state.

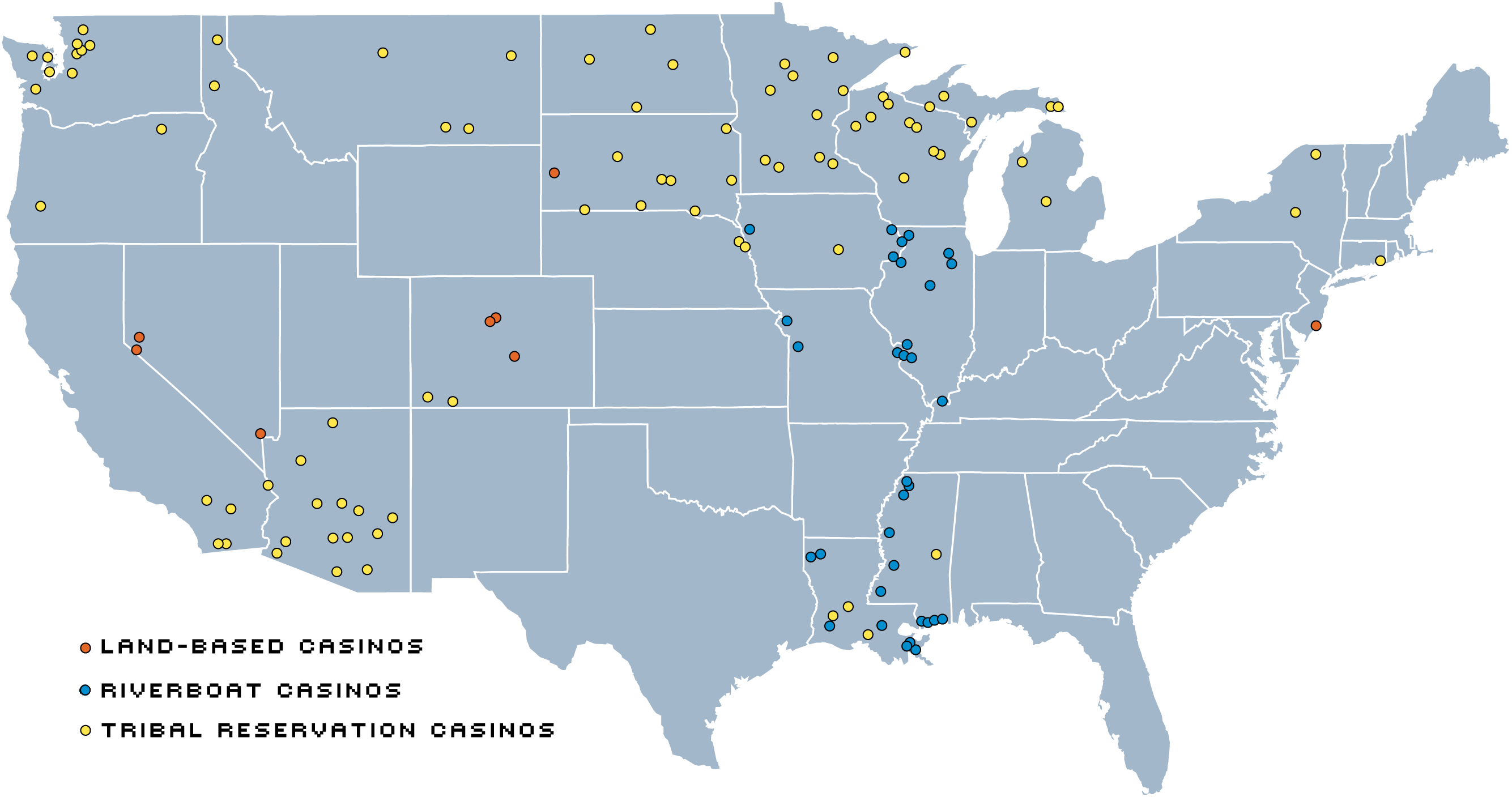

Casino Gambling in the United States

NOTES: Nevada has about 2,200 gambling establishments in all counties. The three major sites are "pinned" on the map. Alaska and Hawaii currently do not have casino gambling. Tribal reservation information is current through May 2, 1994. Land-based and riverboat casino information is current through June 24, 1994.

SOURCES: Land-based and riverboat casinos: State departments of gaming or state gaming commissions. Tribal reservation casinos: National Indian Gaming Commission.

Indiana

Indiana enacted its gambling law in July 1993, allowing individual counties and municipalities to ask voters if they want riverboats in their area. Currently, the Indiana Gaming Commission has only five licenses to grant to Ohio River communities; six counties, across the river from Cincinnati and Louisville, have already passed referendums. The first boat is expected to open by the end of this year. As in the other states, Indiana will impose admission and wagering taxes on the casinos. The state retains 15 percent of adjusted gross revenues, and the local and county governments each get 2 ½ percent. Of the $2.50 admission tax, one dollar each goes to each the local and county governments, and 50 cents goes to the state. Unlike Missouri, Indiana does not have a loss-limit provision. As in Illinois and Missouri, dockside gambling is allowed at the boat captain's discretion for safety. This allowance for dockside gambling, though, is still more restrictive than that in other states, for example, Mississippi.

Mississippi

Mississippi's first boat opened in August 1992 in Biloxi. By the end of 1992, five boats had opened, four on the Gulf Coast and one on the Mississippi River in Tunica County. In 1993, another 12 boats opened for business, four of them in Tunica. This year, nine more boats opened by June, three in Tunica. Mississippi is now second to Las Vegas in total square footage of gaming space. By July 1995, the state predicts there will be more than 40 riverboats operating in the state. Tunica County alone has at least five more casinos slated to open this year and has transformed itself from one of the poorest counties in the nation to one of the fastest growing.

Unlike other states, Mississippi allows dockside gambling. Thus, operating costs for the riverboats are dramatically reduced because they do not incur the costs of cruising on the river. Many boats, in fact, do not even have engines or wheelhouses. In addition, Mississippi does not impose a loss-limit on individuals. This has led to Mississippi raising more gambling revenues than any other state except Nevada and New Jersey. For example, in 1993, with 17 boats operating by the end of the year, Mississippi boats' adjusted gross revenues were about $790 million. In Illinois, 10 boats in 1993 had adjusted gross revenues of about $606 million.

Mississippi also has a more complex taxing scheme—it imposes a progressive rather than a flat wagering tax. Essentially, the state collects an increasing percentage of monthly adjusted gross revenues: 4 percent on the first $50,000, 6 percent on the next $84,000, and 8 percent on anything above $134,000. Local taxes follow the same scheme with much lower rates, and individual counties and cities make different provisions.

Much of this fanfare may cool because of the riverboat casinos in Louisiana, especially those in the New Orleans area. On top of this, a land-based casino, which is a greater revenue generator than a riverboat, will soon open in New Orleans. Direct competition with these facilities, however, will affect the Gulf Coast boats before it reaches those up north. New Orleans' greater ability to attract visitors because of convention and sporting facilities, as well as the city's well-known appeal as a tourist destination, will hurt Mississippi, but the extent of the effect remains to be seen. Until then, Mississippi has a head start and the experience its competition does not.

Endnotes

- There is one exception in St. Louis for a boat that does not move under its own power. [back to text]

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us