Community Profile: Stayed in America: Manufacturing Jobs Aren't Leaving Seymour, Ind.

Photo Gallery | Article

Photo Gallery - Seymour, Ind.

A major expansion is under way at the Cummins plant after it was chosen over plants in Europe and India to build a new line of engines. Employment at the Seymour plant is expected to more than double by 2015. Photo Susan C. Thomson

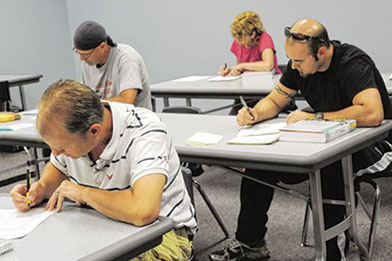

Industry and other community leaders have emphasized postsecondary education to ensure a trained workforce in the Seymour area. At the Jackson County Learning Center, which opened in 2010 at a cost of $2.4 million, adult students can take classes in job-related skills and toward high school diplomas and college degrees. © Photo courtesy of The Tribune newspaper (Seymour, Ind.)

At auto parts maker Aisin U.S.A. Manufacturing, employee Gordon Bell works on a seat adjuster. Aisin is the largest employer in town. It was the first North American plant for its parent company, Aisin Seiki Co. Ltd. of Japan. Photo courtesy of Aisin U.S.A. Manufacturing

The 94-bed Schneck Medical Center helps Seymour attract new industries and residents. Photo by Susan C. Thomson

Officials say the city’s most critical need is more and newer housing. Blocks of small houses like these, dating from the mid-20th century, surround downtown. Photo by Susan C. Thomson

Income from a tax increment financing district is paying for some cosmetic improvements to buildings downtown, which has lost retail business to the road to Interstate 65. Photo by Susan C. Thomson

Hundreds of skilled manufacturing jobs that were at risk for leaving this country are bound instead for Seymour, Ind. A plant in the city won them by outbidding two sister factories overseas for the opportunity to build a new line of sophisticated high-horsepower engines for power plants and other heavy industries.

"The competition was Europe and India," but the local plant prevailed on its record of safety, quality and profitability, says Darren Wildman, manager of the Seymour location of Cummins, an international company based in Columbus, Ind.

On the basis of that 2010 decision, the plant has embarked on a $219 million expansion that will roughly double factory space and add an office building and warehouses. The new jobs have begun arriving, boosting employment at the plant by about 200 since then. Wildman estimates that when the project wraps up in 2015, Cummins will employ about 1,200 people in town, many of them engineers and other professionals at an average wage of $38 an hour.

Along with those jobs, the area stands to gain up to $5 million from a special Indiana state tax incentive that the plant won for being a growing high-technology business. The proceeds from the tax incentive will be turned over to the community to support its ongoing workforce training.

That has been a priority since local leaders realized several years ago that postsecondary education "was not at a level that it needed to be" for purposes of economic development, says C.W. "Bud" Walther, president of the Community Foundation of Jackson County, where Seymour is located. The result was the Jackson County Education Coalition. The group's several initiatives came to major fruition in 2010 with the opening of the $2.4 million Jackson County Learning Center, a one-stop location for two- and four-year college classes, GED preparation and job-related short courses.

To Dan Hodge, executive director of the coalition, its overarching purpose is clear. "We have to do a better job to prepare people for some of these new high-tech jobs," which especially require a more rigorous math and science background than the factory jobs of the past, he says.

Such a philosophy is consistent with that of the Cummins plant, Wildman says. The plant has its own in-house continuing education programs. "We want to drive improvement in our employees' knowledge," he says.

The Cummins project represents "the largest investment at any one time in Seymour," says Jim Plump, executive director of the Jackson County Industrial Development Corp. Add the company's $5 million investment in workforce education, and the benefits will accrue "for many years to come."

Cummins was but one contributor to the 500 jobs Plump calculates Seymour gained in 2012, a banner year by that measure. By fall, the city's unemployment rate had dropped to 6.4 percent—a far cry from the city's spike above 12 percent in June 2009.

Dependence on Auto Industry

That roller-coaster rate is, to a great extent, a barometer of the global auto industry and Seymour's dependence on it by way of its top two employers, parts makers Valeo Sylvania and Aisin U.S.A. Manufacturing.

Valeo Sylvania has deep roots in Seymour, where it began in the 1970s as GTE Sylvania. It is now a joint German-French venture, making headlamps and other automotive lighting products. Its long-term record has been one of "consistent expansion" and "good-paying technical kinds of jobs," says David Geis, president and chief executive of Jackson County Bank.

Aisin is the newer arrival, the first North American plant for its parent, Aisin Seiki Co. Ltd. of Japan. The Seymour plant makes door frames, latching systems, trim molding and other auto parts. It began small, with about 100 people, in the mid-1980s, which was about the same time that its first client, the Toyota plant 120 miles away in Georgetown, Ky., opened for business. Other customers, foreign and domestic, quickly followed, and the plant grew exponentially.

Seymour lies on Interstate 65, roughly halfway between Louisville, Ky., and Indianapolis, Ind. The town is also a two- to three-hour interstate drive away from several auto plants. Given the geography, it makes sense to Plump that the city should have become a center of auto parts making.

Seymour's growing dependence on that sector became evident during the recession, when, according to Plump, both parts companies were "very hard hit." They weren't alone, however. "Hundreds of jobs were lost across the board, even at the Walmart distribution center," he adds.

At Aisin during that tough time, employees "had to make a lot of sacrifices," recalls Shawn Deppen, general manager–corporate production department. Salaried staff took pay cuts, hourly workers' pay was frozen and retirement incentives were offered, he says. Then, when the industry came back, "it came back strong," bringing Aisin along with it.

By 2012, Valeo Sylvania also was back on what Geis describes as "a good path." The year found both suppliers in "fast forward" gear again, announcing plant additions and winning state tax credits tied to the creation of 300 jobs between them. Both were also granted 10-year phase-ins of their incremental local real estate and personal property taxes. The deals are typical of those the Industrial Development Corp. puts together for companies relocating to or expanding in Seymour. Cummins, in addition to its special high-tech award, previously received a similar package of state and local incentives.

So did Pet Supplies Plus. The expanding chain of more than 250 stores in 23 states closed two existing distribution centers in Michigan and consolidated those operations in Seymour in 2012, hiring more than 200 people, including temporaries and part-timers.

Although small by Seymour standards, the company brought what Plump sees as a welcome element of needed diversification to an automotive-dominated economic base. Toward that end as well, he views Kremers Urban Pharmaceuticals as coming on promisingly strong. The fast-growing maker of generic drugs, once a small Seymour start-up, was acquired in 2006 by Belgium-based UCB. The company hires, among others, chemists and physicists, including Ph.D.s, for "excellent high-paying jobs," he says.

Luring New Talent to Town

These are not the kinds of employees readily available in such a small town, nor are the professionals Cummins will continue to hire. Carolyn Ruml, human resources manager at the new Pet Supplies Plus distribution center, says she had to look elsewhere for managers and supervisors. The same goes for physicians, says Gary Meyer, president and chief executive of Jackson County-owned Schneck Medical Center.

The 94-bed center, which underwent $60 million in renovations and additions between 2006 and 2009, is "a big, big selling point" for Seymour, Plump says.

The same can't be said for downtown. Mayor Craig Luedeman concedes it has seen more vibrant days. Those were before the mom-and-pop stores began losing business to the chain restaurants, stores, gas stations and motels that now line the two-mile stretch of Highway 50 leading into town from the interstate.

However, with income from a citywide tax increment financing district, some downtown storefronts are being upgraded, Luedeman says. Those measures will still leave the downtown ringed with blocks and blocks of tiny homes dating to the mid-1900s, evidence of what he and others agree is Seymour's biggest shortcoming when it comes to attracting residents.

"We need higher-end apartments and houses," the mayor says. "Our industries tell us that."

As they hire more new employees from out of town, the overriding question on many local minds is where these people are going to live. Newer, larger, more-attractive houses can be found on the fringes of town, but new construction has recently been limited, says banker Geis. In his view, the more pressing need is upscale apartments "with nice amenities" like swimming pools. Newcomers will likely be happy to rent for a couple of years before they buy, he theorizes.

An immediate alternative is Columbus, Cummins' headquarters city, 20 miles north on Interstate 65, where Wildman, for instance, chooses to live. It's also not unheard of for workers to commute to Seymour from Indianapolis or Louisville.

Bardstown/Nelson County, Ky., by the numbers

| POPULATION FOR CITY/COUNTY |

18,283 (1) / 42,966 (1)

|

| LABOR FORCE |

NA / 21,.441 (2)

|

| UNEMPLOYMENT RATE |

6.4% (1) / 6.5% (2)

|

| PER CAPITA PERSONAL INCOME |

NA / $32,941 (3)

|

| (1) U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 estimate. | |

| (2) BLS/Haver, October 2012, seasonally adjusted. | |

| (3) BEA/Haver, 2011. | |

| Largest Employers | |

| Aisin U.S.A. Manufacturing Inc. |

1,777

|

| Valeo Sylvania |

1,250

|

| Walmart Distribution and Transportation |

1,105

|

| Schneck Medical Center |

862

|

| Cummins |

515

|

| Kremers Urban Pharmaceuticals |

511

|

| SOURCE: Jackson County Industrial Development Corp. | |

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us