Commercial Real Estate: A Drag for Some Banks but Maybe Not for U.S. Economy

The U.S. economy appears to be on the road to recovery following the deepest and longest recession in the post-World War II period. Despite this improvement, some analysts and policymakers are increasingly concerned about deteriorating conditions in the commercial real estate (CRE) sector. Defaults on CRE loans have contributed to the recent upsurge in bank failures and a sharp increase in nonperforming loans of banks. The Federal Open Market Committee noted at its Sept. 23, 2009, meeting that "many regional and small banks were vulnerable to the deteriorating performance of commercial real estate loans."1

How large is the commercial real estate exposure of banks, and what is the likelihood that problems in this sector will be severe enough to derail the U.S. economic recovery?

CRE Exposure

The CRE sector has faced sharp contraction over the past year, paralleling the bust that unfolded in the housing sector two years ago. For example, the value of private commercial and office (hereafter commercial) construction totaled a little less than $140 billion in 2008, about unchanged from the previous year.2 By September 2009, the nominal value of commercial construction had declined by roughly 35 percent to $90.2 billion.

Like residential housing, commercial construction depends heavily on mortgage financing—either directly from commercial banks and thrifts, indirectly through

investors in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) or through other conduits, such as private equity funds or life insurance companies. As of June 30, 2009, the size of the outstanding debt associated with the commercial real estate sector was $3.5 trillion.3 About half of this amount ($1.7 trillion) was held by banks and thrifts. Of the rest, half was held as collateral for CMBS, and the other half was held by investors.

When analyzing commercial banks' exposure to the downturn in the CRE market, it is helpful to first consider how the valuation of these loans can change over time. Like any asset, the market value of a commercial property depends on its expected rate of return over time. This return depends on both macroeconomic factors, such as the health of the economy (both nationally and locally), expected inflation and the market interest rate over the life of the loan. But the return also depends on microeconomic factors, such as vacancy rates, property taxes, land use regulations and the price of land.

As economic conditions deteriorated during the latest recession, the CRE market affected commercial banks, investors and other financial institutions in a couple of key ways. First, sales at businesses slowed sharply and then began to decline, causing some firms to go out of business, vacancy rates to rise and property prices (and rents) to fall. The downturn in commercial property prices during this cycle was particularly severe. By one measure, commercial property prices have declined by nearly 41 percent since their peak in October 2007.4

As CRE mortgage defaults and delinquency rates increased, banks naturally increased the level of their loan loss reserves, which adversely affected their earnings. Moreover, in this downturn, larger banks were also affected by a second

factor—the valuations of commercial mortgage-backed securities that are held on their balance sheets. As the value of the collateral that determines the price of the CMBS declined, commercial banks were forced to mark down the value of these assets on their balance sheets.5 To compensate, banks were forced to raise additional capital or suspend dividends.

Now, as the housing market appears to be stabilizing, the quality of banks' CRE loans is deteriorating. In the past year, average nonperforming CRE loans (loans that are 90 or more days past due or loans not accruing interest) as a percentage of risk-based capital has grown considerably, from 4.47 percent in September 2008 to 7.4 percent in September 2009. Within the banking industry, community banks (banks with assets less than $1 billion) have 30.7 percent of their loans in CRE compared with 12.1 percent for the largest banks (banks with assets greater than $100 billion).

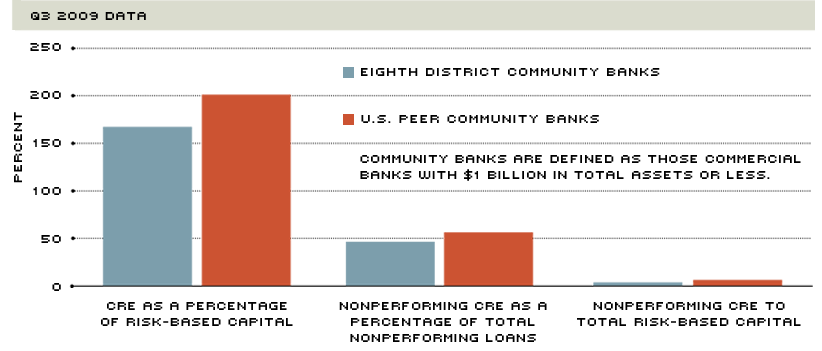

Although community banks are exposed to challenges in the CRE property markets, the accompanying chart indicates that community banks in the Eighth Federal Reserve District have relatively lower levels of CRE exposure than their national peers do. By nature of their business model, banks operate with relatively low levels of capital. As such, CRE loans often represent a multiple of capital. For Eighth District community banks, CRE comprises roughly 167 percent of risk-based capital, as opposed to 201 percent for peer banks. In addition, nonperforming CRE makes up roughly 47 percent of Eighth District community banks' nonperforming portfolio, while it makes up nearly 56 percent of nonperforming loans for peer banks. Most important, nonperforming CRE loans make up only 4 percent of Eighth District banks' risk-based capital, meaning that, as a group, these banks have an adequate buffer to handle CRE-related losses.

Eighth District Community Bank CRE Exposure versus National Peers

SOURCE: Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income for Banks (Call Reports)

Will CRE Derail the Economy?

The collapse in the CRE market during the late 1980s and early 1990s offers some guidance about the potential effects on the U.S. macroeconomy stemming from the current deterioration in CRE loan performance. During the economic boom that followed the deep recession in the early 1980s, many banking organizations weakened underwriting standards on CRE loans. By the late 1980s, the CRE market was experiencing tremendous stress, leading to a collapse in CRE market activity. The collapse in the CRE market caused considerable turmoil in the banking industry,

leading to tremendous losses and a large number of bank failures. From 1987 to 1992, a little more than 1,900 banks and thrifts failed, which cost the FDIC deposit insurance funds roughly $386 billion in real terms.6 And yet, while the economy experienced a recession from July 1990 to March 1991, it's not entirely clear that the CRE crisis was the major factor that caused the recession. However, the CRE collapse and its effect on construction activity and bank performance probably contributed to the relatively weak recovery.7

Today, similar concerns are being raised about the weakness in CRE. As the economy transitions from recession to recovery, the number of bank failures is rising: From January 2009 through early December, 130 commercial banks and thrifts failed, the largest number since 1992. What is not yet known at this point, though, is whether the likelihood of further CRE losses will threaten to further weaken the banking system, which is beginning to recover from the housing bust and the financial crisis. According to one estimate, almost $500 billion of CRE loans will be maturing over the next few years, a potentially significant default risk if these loans are not able to be refinanced.8 Despite these difficulties, most forecasters continue to see steady improvement in economic growth, rising employment and relatively low inflation in 2010 and 2011.

CRE loans may pose a significant risk for community banks in the year ahead. Just as in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it is possible that today's commercial real estate problems will produce adverse economic outcomes. However, the impact is most likely to be seen at the local level than at the national level.

Endnotes

- For minutes of the Sept. 23, 2009, FOMC meeting, see www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20090923.htm. [back to text]

- Private nonresidential construction totaled about $416 billion in 2008. [back to text]

- The commercial real estate total cited here includes outstanding debt on multifamily residential mortgages. In comparison, the outstanding debt associated with the residential sector totaled about $11 trillion. These data are published in the Federal Reserve's Flow of Funds report (Z.9, Table L.217). [back to text]

- See the Moodys/REAL Commercial Property Index at http://web.mit.edu/cre/research/credl/rca.html. [back to text]

- In general, community banks and regional banks have little or no exposure to CMBS compared with large banks' exposure. [back to text]

- See FDIC. [back to text]

- See American Economic Review. [back to text]

- See Greenlee. [back to text]

References

American Economic Review. May 1993. Vol. 83, No. 2. Three papers on the recession of 1990-91, originally presented at an American Economic Association conference in 1992.

Greenlee, Jon D. Testimony on residential and commercial real estate before the Subcommittee on Domestic Policy, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, U.S. House of Representatives, in Atlanta, Ga., on Nov. 2, 2009.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. History of the Eighties—Lessons for the Future. Vol 1: An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s. See especially Chapter 3. FDIC: 1997. Deposit insurance losses come from FDIC's Historical Statistics on Banking; see www2.fdic.gov/hsob/. Deposit insurance loss figure in September 2009 real dollars.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us