Community Profile: Breaking Out—Success in Marion, Ill., Not Confined to Prison

Usually when people hear about Marion, Ill., it has less to do with good news and more to do with bad dudes. This town is, after all, home turf of the federal penitentiary that in 1963 replaced the notorious Alcatraz prison. Today, the Marion prison remains one of two super maximum facilities in the federal system.

But beyond the forbidding—and expanding—walls of the prison is a community that, thanks to several recent successes, is flush with confidence in what it can achieve. The town has carved out its own economic identity and become more than just the exit off Interstate 57 that Southern Illinois University students take on their way to Carbondale. If the new collaborative approach that area officials have taken continues to bear fruit, outsiders may have little reason to ask the kind of question once posed by a Canadian financier, who on a business trip here turned to a local developer and asked, “Could you please tell me where in the hell I am?”

“A Growth Industry”

The Marion penitentiary houses 484 inmates, with an additional 330 serving time at a minimum-security camp elsewhere on the grounds. More than 350 employees work at the prison, with an additional 70 expected to be hired by July, when an expansion to the maximum-security area is completed.

“It’s unfortunate, but this is a growth industry,” says Kevin Murphy, executive assistant at the prison. “It’s a sad commentary, but it’s a fact of life.”

|

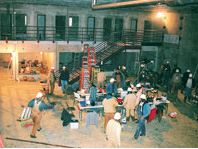

| The federal penitentiary in Marion is undergoing a $21 million expansion (above) that will add 252 cells by July. |

Inmates at Marion have committed serious crimes. They are sent here after exhibiting destructive behavior at other federal institutions. Prisoners are confined to their solitary cells for more than 20 hours each day and spend an average of three to five years in Marion. Before being allowed to transfer to another prison, they must display a pattern of good behavior.

As part of the $21 million expansion, 252 cells are under construction. Murphy says the new hires will add $3 million in payroll to the existing $25 million in staff salaries.

While studying the topic of prisons’ effects on communities, one local labor market economist learned that many small towns in southern Illinois have lobbied hard to attract state correctional facilities in recent years. Mike Vessell of the Illinois Department of Employment Security says that in counties south of Interstate 70, employment at prisons has increased by more than 2,200 over the past decade as civic leaders try to fill the gap caused by manufacturing slowdowns.

“The virtue of a prison or a university or a seat of government is that it generates employment with very little unemployment,” Vessell says. “Not many politicians get laid off, and not many prison guards get laid off. So what you have is a very stable workforce and a solid floor underneath your economy.”

Vessell adds that the jobs at prisons generally pay well and offer good benefit and retirement plans.

E.A. Stepp, warden at the Marion prison, says: “I think our economic impact to the community is huge. In addition, we make a concerted effort to do most of our purchasing for day-to-day operations from local businesses.”

If there are any drawbacks to having some of society’s most hardened criminals living in Marion, you won’t hear about them from the town’s longtime mayor, Robert L. Butler, who took office the year before the prison opened.

“I tell people that we’ve never had any negative aspects, even when we had John Gotti here,” Butler says. “People would call me and ask, ‘What do you think of having the Godfather there in your city?’ I’d tell them, ‘Look, he’s in a maximum-security operation. He’s not going anywhere.’”

Lucky 13

It’s not difficult to notice where the lion’s share of Marion’s growth is occurring—it’s along Route 13, particularly the stretch west of I-57 that ultimately connects to Carbondale 15 miles down the road.

|

| Marion’s landmark clock tower graces the center of downtown. |

“Virtually all of the significant expansion has been along this corridor because it really is the umbilical cord for the area,” says Dutch Doelitzsch, chairman and CEO of the Regional Economic Development Corp. (REDCO).

A drive down this main artery reveals the following:

- a new hospital, Heartland Regional Medical Center,which opened its doors in December;

- the Robert L. Butler Industrial Park, home of a 20-acre Circuit City distribution center, as well as two medical insurance processing centers, including a new Blue Cross/Blue Shield office that will open in March and employ about 500

- the new REDCO Industrial Park, whose first tenant—Aisin, a Japanese auto parts supplier—opened in July and employs 200;

- the Williamson County airport, which is currently undergoing a runway expansion;

- the 900,000 square-foot Illinois Centre Mall, built in the early 1990s; and • a new Home Depot, just opened in November.

Thomas Wimberly, executive director of REDCO, says the area’s ability to land Circuit City nearly two years ago was crucial: “It all started with Circuit City. When they plopped down a $34 million, 1 million square-foot facility in a southern Illinois cornfield, it gained a lot of attention.”

Formed nearly four years ago, REDCO represents all of Williamson County, which also includes the city of Herrin. Doelitzsch credits REDCO for channeling the interests of disparate groups into one united approach.

“We have a number of communities that for years competed with each other,” he says. “We have been able to put that aside and look at things with a broader focus. When we deal with an incoming industry considering us as a potential site, it comes across early and clearly that this is not a single-community effort; it’s a multi-community effort.”

Wimberly says: “Once you start the momentum in industrial growth, it feeds on itself. The minute you complete one project, you’ve got to start on another. You have to keep the momentum going or it will die on its feet.”

While some of the construction around here results from companies like Circuit City and Aisin coming to town, other structures, like the new hospital and Blue Cross building, provide homes for employers already part of Marion’s business landscape. Effort will be required to fill the vacancies at their old locations. The city owns the old hospital property near downtown, and Mayor Butler says he is exploring redevelopment opportunities.

Digging Up Coal

|

| When completed in mid-2003, the Southern Illinois Power Cooperative’s new bed boiler will enable the co-op to increase its consumption of Illinois coal by as much as 50 percent. |

There was a time when Williamson County residents were less concerned with what was on top of the ground than underneath it: coal. Vessell, of the Illinois employment department, reports that the number of coal miners in the county peaked at around 800 in the early 1980s. Today, that figure is down to about 50. And the number of coal mines operating in or near Marion has dropped from four to one small active strip mine.

Coal is plentiful throughout southern Illinois, but the area’s supply is high in sulfur, which is associated with acid rain. The high cost of removing sulfur in order to comply with environmental regulations has lowered demand. But a $103 million project by the Southern Illinois Power Cooperative (SIPC) at its Marion generating station will provide a boost to the state’s coal producers while also burning coal more cleanly.

SIPC, which supplies power to six other rural cooperatives for a total of 80,000 accounts, is in the final stages of completing a new fluidized bed boiler that will use the latest coal-cleaning technologies. The new boiler, which will be in operation by mid-year, will replace three older boilers at the plant.

The cooperative buys nearly all of its coal from mines within 50 miles of its plant. Dick Myott, Planning and Environmental Department manager at the plant, says the new boiler will increase SIPC’s consumption of Illinois coal by as much as 50 percent to 1.2 million tons annually.

“The biggest benefit,” Myott says, “is that we’re going to continue to have reliable, low-cost power for our members in the future. That allows industries to come in because they know that energy is going to be available.”

| Marion, Ill., By the Numbers |

|

|---|---|

| Population | 16,035 |

| Labor Force | 28,839 |

| Unemployment Rate | 4.3% |

| Per Capita Personal Income | $22,641 |

| Top Five Employers: | |

| School District | 750 |

| U.S. Veterans Administration | 583 |

| Marion Pepsi-Cola Bottling | 450 |

| General Dynamics | 420 |

| Verizon North | 400 |

NOTES: Statistics for labor force, unemployment rate and per capita personal income include all of Williamson County. Labor force is from 2001. Unemployment rate is from October 2002.

Per capita personal income is from 2000.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us