Health Insurance in America: Searching for a Cure

Fixing what ails the U.S. health care industry is consistently listed in national polls as one of America's major concerns. Escalating costs and a rising proportion of Americans without health insurance have propelled health care into a major economic, political and social issue. It's estimated that Americans will have allocated about 14 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) to health care in 1992—more than $800 billion—an almost three-fold increase from 1960. And despite the unparalleled range of public and private health insurance options available to help pay for this care, more than 35 million Americans, or 14 percent of the population, have no health insurance of any kind.

Proposed cures for these problems range from a government-run, national health care system like Canada's to market-based, private sector reforms. Any major reforms will likely involve both the government and the private sector. So far, the most interesting—and fruitful—reforms have been at the state level. During 1991, legislators in every state introduced some sort of health reform plan. These efforts have focused on reducing the costs of health insurance and increasing its availability.

The Drive to Self-Insurance

The move toward self-insurance has changed the way health insurance companies compute premiums, especially for small groups. This trend largely explains the rise in health insurance costs and the problems small firms encounter when they want to purchase policies for their employees.

Though it started in the 1950s, the trend toward self-insurance hit its stride in the 1970s. Because most private insurance companies were basing their premiums on the actual medical claims experience of the insured group (called the experience rating system), many large companies found it feasible to self-insure: Their work forces were large enough so that aggregate medical experience and expenses, except for medical price inflation, varied little from year to year. This made it cost-effective for large companies to assume the financial risks of illness and non-job-related injuries, instead of paying for the services of insurance companies.

Government regulation encouraged the move toward self-insurance. In most states, insurance companies were required to pay a premium tax, which they passed on to policyholders in the form of higher premiums. Self-insured companies could avoid this cost. Many states also began mandating that specific services—for example, substance abuse treatment—be included in health insurance policies, raising their cost. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, however, prohibited states from enforcing these mandates on self-insurance plans. These developments spurred a dramatic increase in the proportion of companies that self-insure; currently about 55 percent of the commercial health insurance business is accounted for by companies that assume all or part of the responsibility for paying medical claims.

Many early health insurance plans, including those of Blue Cross/Blue Shield, used the community rating system to compute premiums—everyone in a given area paid the same premium, regardless of health status. The move toward self-insurance, however, expanded the use of the experience rating system in setting premiums, a trend that partially explains the large proportion of Americans without health insurance. Low-risk groups have an incentive to leave the "community" to reduce their premiums because the community premium is based on both high- and low-risk members. To recoup the potential loss from low-risk people leaving the community and self-insuring, private insurers as well as nonprofit providers like Blue Cross/Blue Shield began to use the experience rating system to compute premiums.

The Situation Today

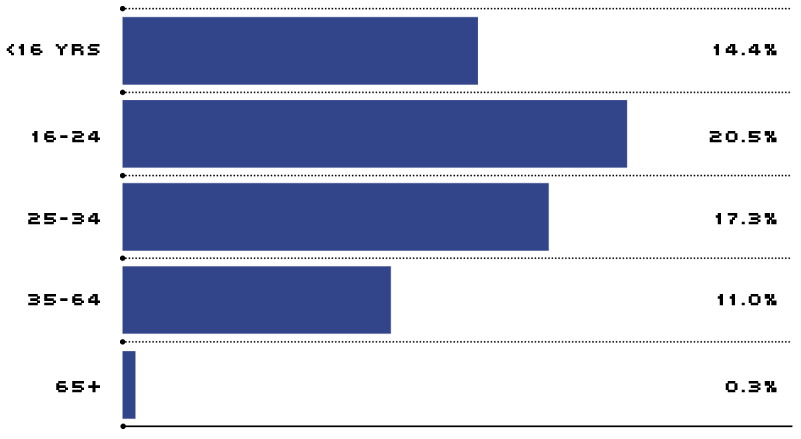

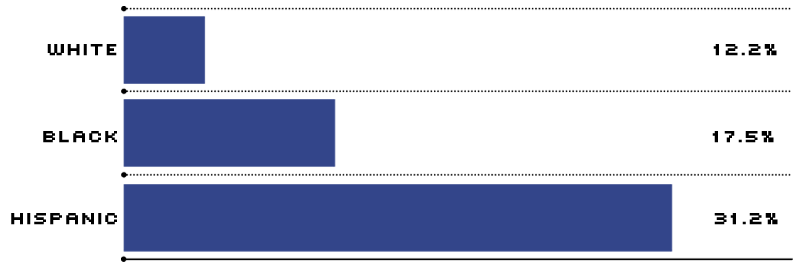

While the evolution in health care and health insurance benefits has resulted in tremendous variety and exhaustive coverage of most medical services, it has been at the expense of millions of Americans without insurance. In France, Germany, Japan and most industrialized countries, in contrast, nearly all citizens are guaranteed health insurance. As one might expect, while the uninsured in America come from all walks of life, minorities, the poor and the young are disproportionately represented (see below). Surprisingly, however, most uninsured Americans have full-time jobs.

In fact, more than 75 percent of the uninsured in America are workers or their dependents. Employers cite the high cost of premiums relative to employee wages and company profits when choosing not to offer health insurance benefits. Because most health insurance in America is employer-provided and most uninsured Americans are employed, reform efforts have centered on improvements in insurance at the nation's businesses.

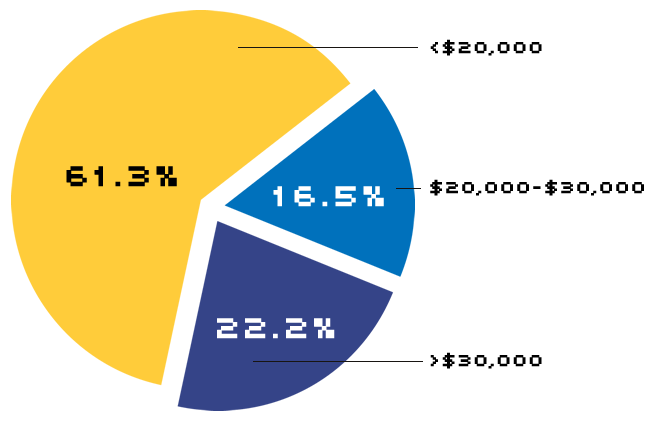

About 20 million workers lack health insurance. The majority of these own their own businesses or work for small companies (see Chart 1). According to General Accounting Office (GAO) surveys, many small business owners believe the primary responsibility for health insurance coverage lies with the employee, not the employer or the government. Others maintain they don't need health insurance to attract and keep good employees.

Workers without Health Insurance

Almost 20 million workers lack health insurance. Including self-employed workers, about two-thirds of the nation's uninsured workers are employed by small companies (less than 100 employees).

In addition, a substantial portion of small-firm workers earn relatively low wages; at an average cost of $3,465 per worker, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, health insurance for these workers represents a high share of total employee compensation. Such employees typically are in no position to turn down cash compensation for health insurance coverage. Most important of all, however, is simply the high cost of health insurance for small firms: At small firms, the fixed costs and risk of providing coverage are spread among fewer enrollees. In addition to the cost factor, increased competition in the health insurance industry has led insurers to move toward practices that further diminish the ability of small firms to gain access to the health insurance market. Among these are stricter medical underwriting practices, preexisting condition exclusions, industry screening and durational ratings.

In one of these, industry screening or redlining, an insurer rejects entire employee groups or charges extremely high premiums based on the high-risk characteristics of that industry. A March 1992 study by the University of Michigan School of Public Health showed that about 15 percent of the nation's small businesses are on the "blackball" list. These businesses are excluded because of high employee turnover, frequent claims submission, a high proportion of older workers on the payroll and hazardous working conditions. Law firms (too litigious) and physician groups (frequent users) are most often denied coverage; others that have trouble are those with transient work forces (hair salons, bars, taxi companies) and those involved in dangerous work (logging, mining).

Another industry practice that limits small business participation, durational rating, is a pricing practice by which early premiums are discounted to reflect the insurer's savings from underwriting and preexisting condition clauses; premiums are raised sharply as the policies age and the insurer expects to pay more in benefits. This pricing policy can lead to the rapid turnover of policies by small firms—which subjects employees to repeated limitations on coverage.

Reform Efforts

While health insurance reform is still being debated in Washington, most states have embarked on reforms of their own. By September 1991, 43 states had adopted some sort of health reform. The general goal of these efforts has been to make insurance coverage more available and more affordable, while minimizing the direct expenditure of state funds. While these efforts vary substantially, most reforms seek to ensure availability by guaranteeing renewal of policies and continuity of policy coverage when employers change insurers, employees change jobs, insurers withdraw coverage or insurers leave the market.

States have also attempted to limit policy prices or price increases. Seventeen states have enacted legislation to limit the range of premium prices insurers may charge small businesses, and many have also limited the amount of annual price increases. From an economic standpoint, however, price restrictions may do more harm than good. Many insurance firms simply will not offer coverage to small companies if such coverage is unprofitable. Among insurers that do continue to offer it, premium prices will likely rise, as they attempt to shift costs to other policyholders to maintain profitability.

Carrots Rather than Sticks

More than 20 states have opted for the carrot rather than the stick approach to health insurance reform, waiving mandates and offering tax incentives to private insurers who provide low-cost, basic benefit plans to small companies. In the Eighth Federal Reserve District, all states except Indiana and Mississippi have adopted or proposed state-mandated benefit waivers and lower-cost plans for small employers. Cost savings can be achieved by excluding services for certain treatments (such as alcoholism/drug abuse) or certain providers (such as chiropractors and psychologists), limiting the number of hospital days allowed in a year, increasing the amount of out-of-pocket expenses borne by the insured or placing caps on annual reimbursements. These plans are usually available only to companies with fewer than 25 employees that do not currently offer health coverage (to avoid the substitution of higher-cost for lower-cost plans). Eligible employers usually have to be without coverage for a year or more before signing up.

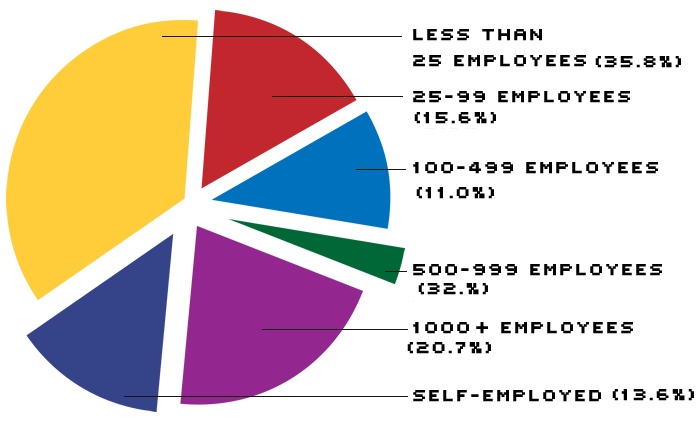

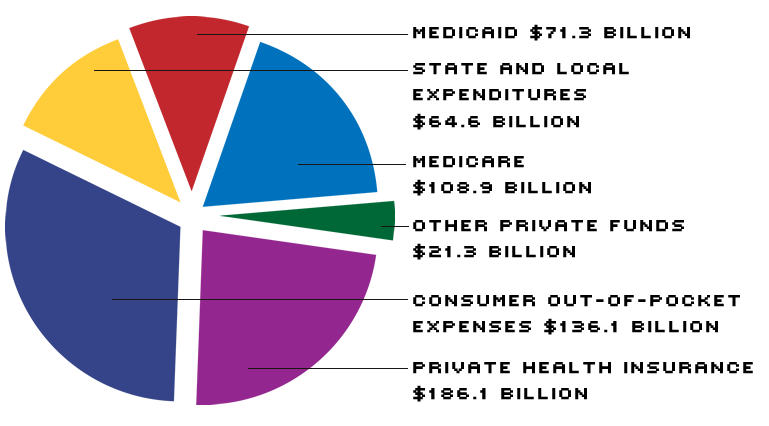

U.S. Personal Health Care Expenditures: Who Pays?

In 1990, the U.S. spent about $588 billion on personal health care. The bill was roughly split between consumers (about 58 percent) and government (about 42 percent). The tab comes to $666.2 billion when you add program administration, the net cost of private health insurance, government public health activities, research and construction.

Thus far, basic benefit plans through Blue Cross/Blue Shield have been marketed in fewer than 10 states, and the results have been modest. Many small business owners say that they are unaware of the plans or that the premiums for these plans are still too expensive. The GAO estimates that eliminating mandates reduces premiums by an average of only 20 percent.

Private insurers, despite the support of their national trade association, have generally not offered these plans; they cite a lack of compatibility between the state laws allowing these plans and standard private insurance practice as a reason for staying on the sidelines. One of the major roadblocks is the requirement in many states that insurers use community rating rather than experience rating in setting premiums. Basic benefit plan advocates say the plans will succeed if they incorporate more managed care options (like health maintenance organizations and preferred provider organizations) and are directly marketed to small businesses.

Sharing the Risks

Another type of reform effort that aims to increase access and affordability is "pooling." When individual firms band together, they can often negotiate premiums comparable to those paid by large, self-insured firms. By September 1991, private small-employer pools had been established in 45 state-controlled all Eighth District states but Arkansas. In Memphis, a program called Tennessee MedTrust provides insurance for about 860 persons employed by small area companies. The program receives no public subsidy but is able to offer premium rates that average 45 percent less than market rates because of discounts it receives from three participating hospitals. There are similar programs for both large and small employers across the District.

Two other types of pools have been established in a number of states. State-sponsored high-risk pools have been set up in 26 states to provide insurance to individuals who are considered high-risk or uninsurable because of current health status, poor health history or hazardous employment. High-risk pools have been adopted or proposed in all seven District states. Covered individuals pay on average about 60 percent of the cost of the plan through premiums; the difference between claims and premium receipts is usually borne by participating insurers, who are assessed an amount proportional to their share of the private market. In some states, the difference is funded by state appropriations, tax surcharges or general revenues. One of the goals of high-risk pools is to eliminate "job lock," whereby people stay in jobs they would otherwise leave because they are afraid of losing health insurance coverage.

Reinsurance pools, which have been adopted in only a few states, allow individual insurers to group high-risk people and their excess medical expenses in a separate pool in which the risks are spread across a larger number of insurers. Most large insurers surveyed by the GAO indicated that the establishment of a reinsurance mechanism in their states would make them more willing to accept other market reforms, such as renewal of all small-group policies, regardless of claim experience. Insurers are split, however, about whether participation in reinsurance pools should be voluntary.

What's Ahead?

Many analysts expect some type of national health care policy to be enacted over the next several years, but they differ on the extent to which the federal and state governments will be involved. Congress has been particularly active on this issue in recent years; during the 1992 session, almost 30 bills related to health insurance were introduced in the House or Senate. The new Clinton Administration has already outlined the bare bones of a reform plan. Many of the specific reforms detailed in the Clinton proposal are already in effect in some states; they include prohibiting insurance companies from excluding persons with preexisting conditions, requiring insurance companies to use community rather than experience rating in setting premiums and setting up purchasing networks for companies and individuals to buy insurance at cheaper group rates. Meanwhile, analysts expect continued activity at the state and local leveling an emphasis on providing insurance to the uninsured. As budgets shrink, many states can ill afford to keep picking up the tab for the uninsured who end up in community hospitals and clinics. There is no miracle cure for the nation's health insurance woes, but a continuation of cooperative efforts among the nation's businesses will no doubt hasten the recovery.

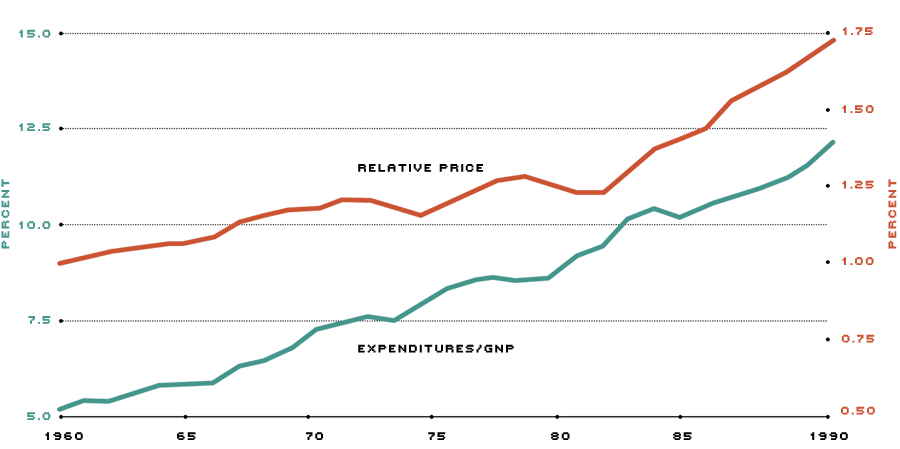

National Health Expenditures as a Percent of GNP and the Relative Price of Health Care

The relative price of health care is calculated as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for medical expenses divided by the CPI less medical expenses, indexed so that 1960=1.

The U.S. spends an ever-increasing portion of its national income on health care (green line). Much of the increase in this proportion is the result of medical price inflation (red line).

References

By the General Accounting Office:

- Health Care Spending Control: The Experience of France, Germany, and Japan, November 1991.

- Access to Health Insurance: State Efforts to Assist Small Businesses, May 1992.

- Access to Health Care: States Respond to Growing Crisis, June 1992.

Health Insurance Association of America. Source Book of Health Insurance Data, 1991.

Schroeder, Michael. "How Are Hair Salons Like Law Offices?" Business Week, October 19, 1992.

Thompson, Roger. "States Take Lead in Health Reform," Nation's Business, April 1992.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us