Bourbon and Whiskey Distillers Face Rosy Tourism, Vexing Tariffs

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Bourbon and other American whiskeys have become targets of retaliatory tariffs amid global trade disputes.

- Distilling whiskey is an important source of economic activity for Kentucky and Tennessee.

- Tourism related to whiskey has provided another way to tap growth from regional distilleries.

For many American whiskey producers, the summer season has traditionally been a time when production is slowed down to allow for annual distillery maintenance, thereby providing producers with the opportunity to plan for the next round of distilling, mixing, storing and bottling that typically begins in the fall. An expected surge in global demand has become a vital part of their planning.

This past summer, however, producers—both large and small—found it much more difficult to plan for the future as they tried to gauge the impact of retaliatory tariffs on American whiskey imposed by U.S. trading partners. First imposed in late June and early July, stiff tariffs have remained in place in key export markets like the European Union (EU).

For the Eighth Federal Reserve District states of Kentucky and Tennessee,Headquartered in St. Louis, the Eighth Federal Reserve District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. This article uses state-level data for Kentucky and Tennessee. the economic and cultural significance of whiskey production makes the current trade situation especially poignant. Kentucky produces about 95 percent of the world’s bourbon, and Tennessee is the home of Jack Daniel’s—the world’s most popular Tennessee whiskey.

The Whiskey Boom

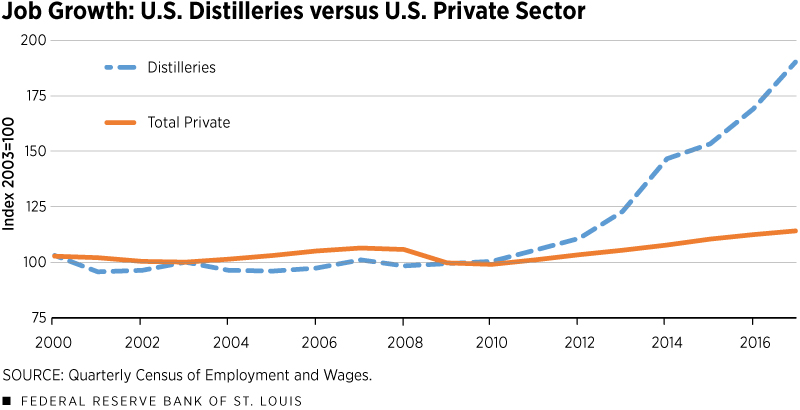

Domestic and foreign demand for U.S. whiskeys has surged in recent years, thanks to improved economic conditions worldwide and a growing taste for premium and craft whiskey products. In the U.S., employment at distilleries (which produce all types of spirits) has almost doubled since 2003, from just over 7,200 jobs to 13,700 in 2017.*

In 2017, combined U.S. revenues for bourbon and other American-style whiskeys like Tennessee and rye hit $3.4 billion, up 8.1 percent from the previous year and up about 160 percent since 2003, according to the Distilled Spirits Council. Of this amount, exports reached $1.13 billion in 2017, an increase of more than 75 percent over the past two decades; 2017 was also the sixth year in a row that exports topped $1 billion. While this represents less than 0.1 percent of total U.S. exports, whiskey makes up 64 percent of the country’s distilled spirit exports.

Kentucky Bourbon

In 1964, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution declaring bourbon a “distinctive product” that can be produced only in the United States.See Bourbon Whiskey Designated As Distinctive Product of U.S. Concurrent Resolutions—April 21, 1964. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-78/pdf/STATUTE-78-Pg1208.pdf Thanks to a combination of climate and other factors, close to 95 percent of all bourbon comes from the state of Kentucky, according to the Kentucky Distillers’ Association (KDA).

Since 2003, the number of distilleries in Kentucky has more than tripled—from 14 to 48 in 2017—and more are being planned for construction or expansion. While the data do not identify the types of spirits produced in these distilleries, it is primarily Kentucky bourbon. Distilleries employ about 4,600 people in Kentucky, which is about one-third of total distillery employment in the U.S. but only 0.3 percent of that state’s total workforce.

While it is difficult to measure the economic impact of the bourbon industry on the state, estimates can be produced. Disentangling the actual production of spirits from other activities, such as inputs in the supply chain and associated tourism, is important for understanding how the industry is being measured. The following steps produce an estimate of the value added from production.

Kentucky is about a $203 billion economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) for the state. The food, beverage and tobacco (FBT) manufacturing industry, a broader sector that includes distilleries, produces about $7.5 billion, or 3.7 percent of state output. Distilleries employ about 15 percent of all FBT workers and pay these workers about 29 percent of all FBT earnings. Using either the employment share or earnings share implies that GDP from distilleries is between $1.1 billion and $2.2 billion per year, respectively, or up to about 1 percent of the state’s economy.

Yet Kentucky’s bourbon industry reaches far beyond the production of spirits. The Kentucky bourbon business generated more than $8.5 billion in annual revenues in 2017, according to a report produced by the University of Louisville’s Urban Studies Institute and the KDA.

The report estimated that bourbon manufacturing had the state’s second-largest job multiplier effect, at around 3.0; that is, every one distillery job results in three additional jobs beyond manufacturing. These estimates could imply that the bourbon industry contributes far more than 1 percent to the state’s economy but likely somewhere around 3 percent.

In addition, Kentucky distillers pay an ad valorem state tax per barrel for every year a barrel ages. Revenues from this tax are used to fund education, public safety, public health and other needs. In 2017, distillers paid close to $18 million in ad valorem barrel taxes.

Tennessee Whiskey

Compared with Kentucky bourbon, there are fewer producers of Tennessee whiskey, in part due to the statewide prohibition that had for many years limited the distillation of drinkable spirits to just three of Tennessee’s 95 counties (Lincoln, Moore and Coffee). This prohibition was lifted in 2009. There are now more than 30 distilleries across the state, with more being planned. Tennessee whiskey can be produced only in the state and following specific processes per various federal and state legislation.

In 2017, Tennessee whiskey was the state’s eighth-largest export, valued at $665 million, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.See State Exports from Tennessee. U.S. Census Bureau. www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/state/data/tn.html There are currently two major producers of Tennessee whiskey: Brown-Forman’s Jack Daniel Distillery, based in Lynchburg, and Cascade Hollow Distilling, which is based in Tullahoma and owned by the U.K.’s Diageo.

Jack Daniel’s is the top-selling American whiskey in the world, accounting for about 70 percent of all U.S. whiskey exports. Foreign sales represent about half of Brown-Forman’s overall sales.

Retaliatory Tariff

In late June and early July, the European Union, Canada, Mexico, Turkey and China responded to aluminum and steel tariffs imposed by the U.S. with tariffs of their own on a variety of U.S. products, including whiskey. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

2018 Tariffs on U.S. Bourbon and Whiskeys

| Country | EU | Canada | Turkey | Mexico | China |

| 2018 Tariff | 25% | 10% | 40% | 25% | 25% |

| 2017 Export Value | $667 million | $48.7 million | $20.2 million | $13.4 million | $8.9 million |

NOTE: Tariff rates as of Oct. 1.

SOURCE: Distilled Spirits Council.

The day Mexico announced its tariff, share prices of major U.S. distillers tumbled on concern that the trade war could escalate. In the EU, which accounts for about a quarter of U.S. whiskey exports, major distributors were expected to raise prices on American whiskey and bourbon brands that they sell in this region. Companies also reportedly built stockpiles in Europe to mitigate the impact of the tariff. For smaller producers, who have indicated they cannot absorb similar price increases, they are considering a price cut in order to maintain market share. Concerns remain that excess supplies of major brands meant for export will weigh on smaller nonexporting U.S. producers.

While the direct impact of the tariff is measured by a percentage increase in prices, a greater concern is the potential loss of foreign markets. Whiskey is a quintessential American product, and producers believe changes in sentiment toward the U.S. will negatively impact the demand for their product. Moreover, unlike other iconic American products like Harley-Davidson motorcycles that have been subject to tariffs, federal law requires that bourbon be produced in the U.S., limiting a distiller’s ability to shift production overseas to offset costs if tariffs remain in place for an extended period.

Tourism—A Bright Spot

Tourism has grown to be a very powerful component to the economics of whiskey in Kentucky and Tennessee. The KDA launched the Kentucky Bourbon Trail in 1999, followed by the Kentucky Bourbon Craft Trail in 2012. In 2017, there were 23 distilleries that participated in the trails, drawing close to 1.2 million visitors. As a comparison, wine-growing Napa Valley in California— a region adjacent to the San Francisco metropolitan area, with a population of over 4.3 million—welcomed 3.5 million visitors in 2016.

A 2014 report by the Urban Studies Institute examined the economic impact of bourbon tourism, finding that whiskey tourists tend to be “relatively affluent” visitors who make “multi-night hotel stays in Kentucky.” The report estimated the economic impact of bourbon tourists on Jefferson County alone equaled $2.5 million per year.

The Tennessee Whiskey Trail, modeled after the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, launched in June 2017. It is an initiative of the Tennessee Distillers Guild and currently features about 25 stops.

Conclusion

A growing U.S. appetite for distilled spirits has fueled rapid growth for distillers of bourbon and other American whiskeys. Amid a solid labor market, U.S. consumers are also more willing to spend on high-end brands. Meanwhile, foreign consumers continue to embrace these spirits as consumable symbols of America.

Foreign sales have been a particular sweet spot for distillers, though recent trade disputes may slow export growth to the EU and other trading partners and weaken the profitability of this business. Despite the new challenge abroad, interest in not only the beverage but the mystique of distilling—as evidenced by whiskey-related tourism—should buffer any international slowdown.

*A previous version of the chart showing job growth at U.S. distilleries relative to that of the U.S. private sector had a mislabeled index year. The chart has been amended.

Endnotes

- Headquartered in St. Louis, the Eighth Federal Reserve District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. This article uses state-level data for Kentucky and Tennessee.

- See Bourbon Whiskey Designated As Distinctive Product of U.S. Concurrent Resolutions—April 21, 1964.

- See State Exports from Tennessee. U.S. Census Bureau.

References

Urban Studies Institute. The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of the Distilling Industry in Kentucky. Report prepared for the Kentucky Distillers’ Association and the Kentucky Agricultural Development Fund, October 2014.

Urban Studies Institute. The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of the Distilling Industry in Kentucky. Report prepared for the Kentucky Distillers’ Association, January 2017.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us