Economic Improvements Anticipated in the Months Ahead

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Although 2020 closed with mixed signals, much stronger GDP and job growth are expected in 2021.

- Several key economic indicators—manufacturers’ orders for core capital goods, industrial production and others—were strong in Q4 2020.

- Inflation remains below the Federal Open Market Committee’s 2% target and rising federal debt has not led to a spike in interest rates.

As 2021 unfolds, the consensus of private-sector forecasters and Federal Reserve policymakers is that the U.S. economy will register strong real gross domestic product (GDP) growth this year and next, with further declines in the unemployment rate.

Robust economic performance would be a welcome development for a nation still recovering from a pandemic that triggered an extraordinarily deep recession. Certainly, some industries have fully recovered and others have thrived during the pandemic, but many have not, and labor markets continue to be impaired. It remains to be seen whether the combination of faster growth and highly stimulative monetary and fiscal policies will begin to lift inflation and inflation expectations.

Mixed Signals Close Out 2020

Although no official pronouncement has been made, the 2020 recession probably ended sometime in late spring or early summer. The economy saw a record decrease and increase in real GDP in the second and third quarters, respectively, but more moderate growth in the fourth quarter. For the year, real GDP fell 2.5%.For the latest on GDP and other key economic indicators, see Economy at a Glance, which is powered by FRED, the St. Louis Fed’s signature economic database.

It’s notable that during the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, forecasters were expecting real GDP to fall by nearly 6% in 2020. Thus, the economy rallied more than expected over the second half of the year. Labor market conditions also continued to improve over the second half of 2020: The unemployment rate fell from 11.1% in June to 6.7% in December.

The fourth-quarter increase in real GDP masked some loss in momentum during the last two months of 2020. A key driver of this weakness was a resurgence in COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths during the fall that spurred many states and localities to strengthen or reinstitute virus containment measures such as lockdowns and social-distancing protocols.

These measures were significant enough to produce a decline in nonfarm payrolls in December. In particular, job cuts in the leisure and hospitality industries were extraordinarily large (-536,000). The containment measures and loss of labor market strength helped trigger declines in personal consumption expenditures (PCE) of 0.7% in November and 0.6% in December.

But other economywide indicators strengthened over the last few months of 2020. First, industrial production rose sharply in December and manufacturers’ new orders for core capital goods—an important barometer for business fixed investment—were at an all-time high in the fourth quarter. Second, housing construction (starts) and total home sales in the fourth quarter of 2020 were at their highest levels since 2005. Third, stock prices finished the year up by more than 16%, and financial market stress remains below average.

A Bullish Narrative for 2021

Although employment growth turned positive in January, payrolls rose by only 49,000, as gains in several services-providing industries remained muted. Still, there are several reasons the economy and labor markets should register much stronger growth in 2021.

As noted above, several key industries ended the year with solid growth. Second, the deployment of several vaccines should reduce containment measures that have hampered spending and employment gains. Third, household spending on leisure, hospitality, dining and travel—services most adversely affected by the pandemic—should rebound strongly as the pandemic begins to fade. And the rebound in spending will be boosted by unusually high levels of household savings because many people reduced their spending on discretionary items during the pandemic.

Fourth, the jolt from increased spending on services will benefit the broader economy because increased incomes of people who work in service-intensive industries will likely lead to increased expenditures on big-ticket items such as autos, appliances and furniture. Fifth, retail inventories are at exceptionally low levels. Thus, stronger consumer spending means that manufacturers will need to boost production to restock retailers’ shelves. Finally, fiscal and monetary policy remain highly accommodative.

Risks to the Outlook

What are some of the threats—termed “downside risks”—to this bullish narrative? One potential risk is that consumers might be reluctant to draw down their savings balances to increase spending. Another potential risk is that vaccines may prove to be less potent than initially thought—particularly against the new variants of COVID-19.

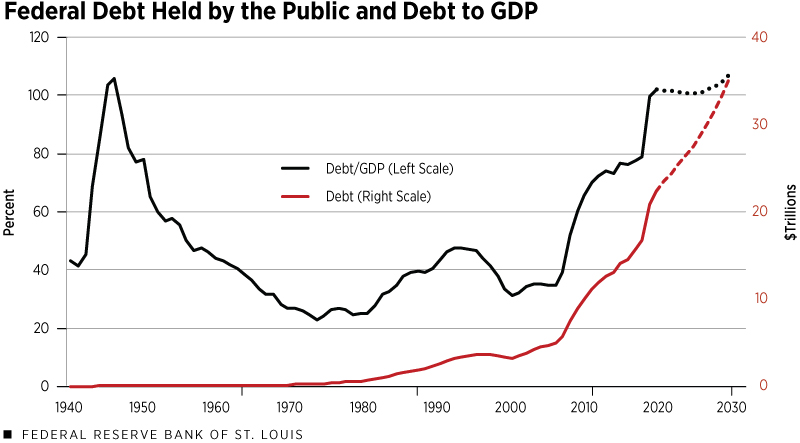

Yet another risk is the worrisome erosion in federal finances. As shown in the figure below, the Congressional Budget Office projects that federal debt held by the public will total more than $35 trillion in 2031, a little more than 107% of GDP. Although rising federal debt levels have not yet led to a meaningful rise in interest rates, history suggests that sharply larger federal budget deficits and rising debt-to-GDP levels could raise interest rates more than expected. With all else being equal, this could dampen spending on interest-sensitive goods and services and, perhaps, lead to lower stock prices.

Another potential downside risk is that rising debt levels and a strong rebound in incomes and spending could trigger rising inflation and inflation expectations. However, inflation was only 1.2% in 2020, and it has mostly remained below the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC’s) 2% inflation target since 2012.

So, there seem to be forces at work that have kept inflation low for a long time. But the Fed’s new monetary policy framework is actively striving to weaken these disinflationary forces. Indeed, the FOMC has signaled that it will no longer “preemptively” tighten monetary policy before inflation reaches the 2% target.

Instead, the new policy will not begin tightening until inflation “moderately” exceeds 2% on a sustained basis. In short, many of the ingredients for higher inflation are there. At this point, though, the majority of forecasters and financial market participants still expect inflation of about 2% in 2021 and 2022.

Kathryn Bokun, a research associate at the Bank, provided research assistance.

- For the latest on GDP and other key economic indicators, see Economy at a Glance, which is powered by FRED, the St. Louis Fed’s signature economic database.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us