Female-Led Firms: Trends and Differences Relative to Male-Led Firms

KEY TAKEAWAYS

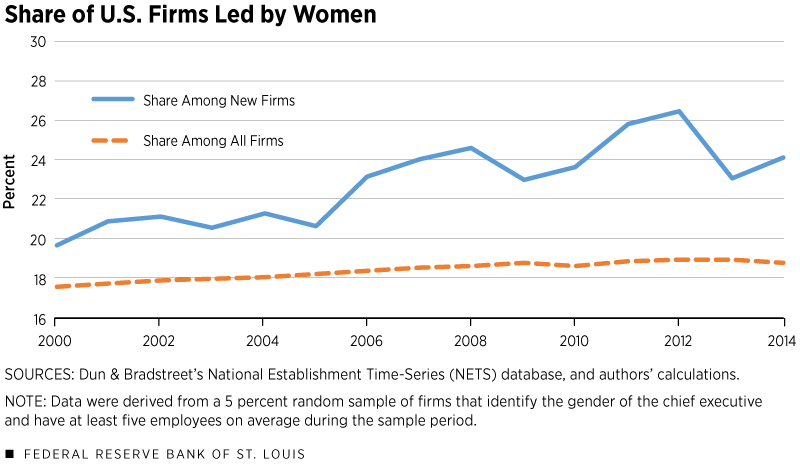

- Despite women’s growing role in the workforce, the share of firms led by women CEOs was only 18.8 percent in 2014, relatively stable from 17.6 percent in 2000.

- Regarding new firms, the share of firms with female CEOs was 24.1 percent in 2014, up from 19.7 percent in 2000.

- Female CEOs lead smaller and younger firms, with similar credit ratings as their male-led counterparts. Women are also more likely to lead nonprofits and proprietorships.

While much work has been done to improve our understanding of women in the workforce, much less is known about their roles as entrepreneurs and executives in the private sector. The goal of this article is to investigate the role played by women in leading firms in the U.S.

To do so, we used the National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) database collected by Dun & Bradstreet, which contains detailed information on the universe of firms in the U.S. over recent decades. Among many other variables that are available, the data set allows us to identify whether the firm’s CEO is a woman; we identify these firms as women-led firms.

The figure and table in this article were computed based on a 5 percent random sample of firms from the NETS database for the period 2000-2014; 2014 is the last year with available data. Given the database is at the establishment level, we analyzed firms by aggregating the database at the headquarters level.

We abstracted very small firms from our analysis by restricting attention to firms with at least five employees on average over the sample period. Additionally, we considered only firms for which the gender of the CEO is not missing.

Has the Share of Women-Led Firms Increased?

We began by investigating the extent to which the prevalence of women-led firms has increased over time. Figure 1 reports the share of firms led by women over time across all firms as well as across new firms.

The figure shows that the share of all firms with a female CEO was very stable over this period: The percentage of women-led firms rose gradually from 17.6 percent in 2000 to 18.8 percent in 2014. In contrast, the share of women-led firms across new firms increased at a faster rate: It rose from 19.7 percent to 24.1 percent over the same period. Despite the significant change in the share of new firms led by women, the small portion of new firms across all firms implies that the share of women-led firms among existing firms had increased very slowly over this time period.

These findings contrast markedly with the increased female labor force participation in the postwar era. While women are becoming increasingly integrated into the labor market, it seems that much progress remains to be done to increase female participation as business leaders and top executives.

Are Women-Led Firms Different?

We then investigated the extent to which women-led firms differ from their male-led counterparts. To do so, we used the data described above to summarize key characteristics of the firms.

The results are presented in the accompanying table, where we contrast salient features of the firms—including size, credit rating and the form of organization—between those with female CEOs and their counterparts with male CEOs.

| Female CEO | Male CEO | |

|---|---|---|

| Firm Size | ||

| Average Sales (Millions of Dollars) | 2.07 | 5.19 |

| Average Number of Employees | 23.40 | 35.30 |

| Average Firm Age | 26.31 | 31.18 |

| Credit Rating | ||

| Average Paydex Credit Score | 71.61 | 71.60 |

| Average Credit Appraisal | 2.48 | 2.50 |

| Public Versus Private | ||

| Public Firms | 0.05% | 0.25% |

| Private Firms | 99.95% | >99.75% |

| Type of Organization | ||

| Nonprofit | 9.26% | 4.45% |

| Proprietorship | 18.36% | 13.73% |

| Partnership | 10.73% | 13.09% |

| Corporation | 61.66% | 68.77% |

| Type of Vendor | ||

| Government Contractor | 2.75% | 3.86% |

SOURCES: Dun & Bradstreet’s National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) database, and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Values for firm size and credit rating are average values in 2014; values for other characteristics are average values from the period 2012-2014. For the distribution of firm organization, the data were adjusted to add up to 100 percent by removing firms that did not report an organization type.

Size. The data set provides two key variables to examine the relationship between the gender of the CEO and firm size: the number of employees and the firm’s annual sales. We found that the size difference between the two types of firms is striking: Compared with firms led by male CEOs, women-led firms have, on average, less than half the sales and about two-thirds of the number of workers. Note that firms led by male CEOs are also older than those with female CEOs, which may account for part of the size difference.

Credit ratings. One of the unique features of the NETS database is that it provides detailed information on firms’ credit scores: the Paydex credit score and a credit appraisal rating. The Paydex credit score is a rating from zero to 100 that rates the timeliness of payments across establishments, with 100 being the highest credit score; it is similar to the FICO credit score for individuals. The credit appraisal rating is available for firms with enough information on various statistics, such as revenue and net worth; the rating ranges from 1 to 4, with 4 being the highest credit appraisal score.

We found that the average credit measures across the two groups of firms are nearly identical. On average, we found that women-led firms have a slightly higher Paydex and a slightly lower credit appraisal than male-led firms; however, the differences are minor. Thus, we conclude that firm creditworthiness does not differ materially between the two groups.

Firm type. The data set also contains information that allows us to examine the relationship between gender and the composition of firms across (1) public versus private, (2) types of organization (i.e., nonprofits, proprietorships, partnerships and corporations), and (3) type of vendor (i.e., government contractor). First, we found that 0.05 percent of firms with female CEOs were public firms, compared with 0.25 percent of firms with male CEOs. Second, we found that female CEOs are more likely to work for nonprofits and proprietorships than their male counterparts, while the latter are more likely to work for partnerships and corporations. Finally, we found that male CEOs are more likely to work for firms that are government contractors.

Conclusion

Our findings show that women are significantly less likely to lead U.S. businesses than men and that this share has remained surprisingly unchanged over the period 2000-2014. Moreover, conditional on leading a business, women are likely to be CEOs of smaller and younger firms. Yet, the creditworthiness of female-led firms is on par with that of their male-led counterparts. Finally, we found that women are more likely to lead nonprofits and proprietorships than men, while men-led firms are more likely to be partnerships, corporations and government contractors.

These findings suggest that more work needs to be done to integrate women into the labor force. In particular, the findings suggest that despite the significant increase in female labor force participation in the postwar era, this does not appear to have led to greater participation of women in the highest executive position at the organizations where they work.

While these findings describe salient differences between firms led by male and female CEOs, they do not explain the causes behind these features. Further research needs to be conducted to identify the forces underlying the observed differences between firms led by male and female CEOs, and potential policies that might help to address these disparities.A recent study that addresses some of these questions is Gayle et al.; see references therein for other related studies.

Endnote

- A recent study that addresses some of these questions is Gayle et al.; see references therein for other related studies.

Reference

Gayle, George-Levi; Golan, Limor; and Miller, Robert A. "Gender Differences in Executive Compensation and Job Mobility." Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 30, No. 4, October 2012, pp. 829-71.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us