Why Are More Credit Unions Buying Community Banks?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Acquiring banks and thrifts has become another way for some credit unions to grow in size.

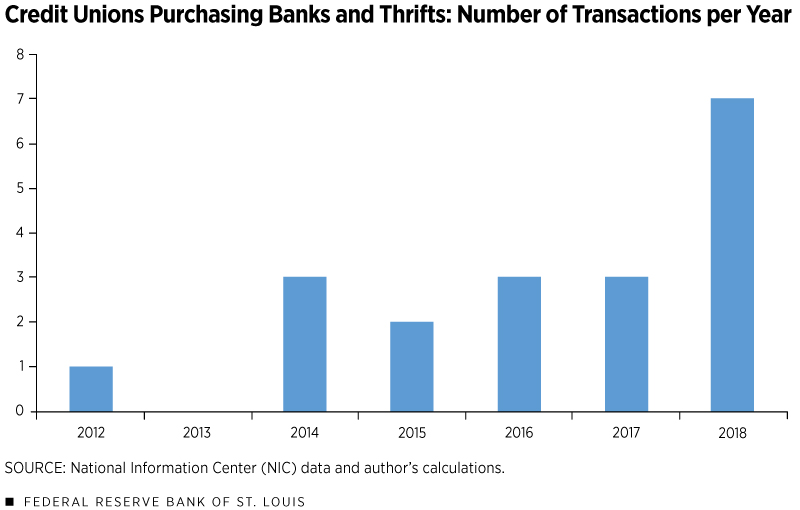

- This trend is growing but remains small - only seven deals in 2018 - because of regulatory and business-model challenges.

- Small banks with strong community ties and banks with different specialties, such as business lending, can be appealing to credit unions.

In the current banking environment, there is a strong perception that bigger is better. Although banks and thrifts (hereafter referred to as “banks”) have been consolidating for decades, the trend has accelerated in recent years. One factor driving this trend is regulatory compliance costs. Research using data from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS) 2018 National Survey of Community Banks has shown that the bigger the bank, the less it spends on regulatory compliance as a percentage of total noninterest expense.See Dahl et al.

Credit unions also face economies of scale.See Wheelock and Wilson. In addition to other constraints on their growth, they have field-of-membership requirements: a common bond, a multiple common bond or a community bond.See www.ncua.gov/support-services/credit-union-resources-expansion/field-membership-expansion for further details on the field of membership. State-chartered credit unions may have more or less restrictive membership criteria, depending on the state. Restrictions on their field of membership have relaxed over time, giving credit unions more options for growth than ever before.

One way to grow, of course, is organically—building new branches or obtaining new customers via advertising or through special deals. A much faster way to grow, however, is to purchase another financial institution and integrate it into existing operations. Historically, the vast majority of credit unions expanding via acquisition have done so by buying other credit unions. In the last few years, however, there has been an increase in the incidence of credit unions buying banks. Indeed, there was only one such transaction in 2012, but it had grown to seven transactions by 2018. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Acquiring a Bank vs. Another Credit Union

So what would entice a credit union to pursue a bank instead of another credit union? For one thing, it may be the fastest way to expand into new business lines that are more closely associated with banks (for example, business lending).See www.cuna.org/Advocacy/Priorities/Member-Business-Lending for details. The average ratio of business loans to total loans for the acquiring credit unions in the quarter before the transaction was 8.6 percent, whereas the average for the acquired banks was 33.8 percent. The acquisitions of the commercial banks raised the business-loans-to-total-loans ratio in the credit unions to 10.9 percent.Business lending for both types of institutions consists mainly of commercial and industrial loans, agricultural loans, construction and land development loans, loans secured by nonfarm nonresidential property, and loans secured by farmland.

Moreover, like credit unions, small community banks tend to have strong community ties and know their customers on a more personal level than their large-bank counterparts do. This strong community relationship can be an asset to the acquirer.

Field-of-Membership Issues

Of course, one potential roadblock is field of membership, and a credit union must plan for such considerations early in the process. For example, if a credit union’s membership is limited to employees of a particular corporation, it would be hard-pressed to find a commercial bank whose customer base covers only those same employees.

On the other hand, if a credit union’s field of membership covers all residents of a particular state, it would not be difficult to find a small community bank that serves only that state or a small portion of that state. If that portion is located somewhere other than where the majority of the purchaser’s existing members are located, there is an added bonus of geographic diversification along with some new employees who are familiar with the new area.

It is possible to petition one’s regulator to change the field-of-membership constraint, but there is no guarantee of success, and such a move would need to take place well in advance of any purchase discussions.See Emmons and Schmid.

Other Regulatory Issues

Once a merger has been consummated, the former commercial bank no longer exists as a legal entity, and the acquiring credit union may not use the word “bank” on any of its signage or literature. It must also make clear to depositors that they are no longer under the protection of the FDIC Deposit Insurance Fund, but rather the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund.See Hui. Of course, banks that switch from a national charter to a state charter, or vice versa, also face regulatory issues.

The Bank’s Decision to Sell

The decision to sell a bank is never an easy one. The banks in Table 1 (see below) that have engaged in these transactions are quite small, all well under the $500 million mark. If a bank is struggling to maintain profitability only because of its small size, then a wide variety of financial institutions would likely be able to benefit from the purchase. If the problems are more complex than a mere inability to take advantage of scale economies, however, there are reasons to believe that a credit union might be a preferable suitor.

First, credit unions do not necessarily have the same pressure to generate a return on investment for their shareholders.In this way, they are similar to family-owned or otherwise closely held banks, but these small banks often lack the resources to make acquisitions. Rather, credit unions need only cover their operating costs, provide satisfactory member services and maintain an adequate regulatory capital base. Thus, if a target bank’s profitability is under pressure, a credit union buyer might be more willing to take a chance on the purchase. For the 19 banks listed in Table 1, six of them had a negative return on assets (ROA) as of the quarter before the transaction, and the average ROA was only 0.08 percent.For comparison, the weighted average ROA for all banks under $1 billion in assets from 2012 to 2018 was 1.01 percent.

Second, credit unions might be willing to pay a higher price because of their favorable tax treatment. Unlike commercial banks, credit unions are not subject to profit taxes. If a bank is organized as a C corporation, its profits are taxed once at the corporate level and then taxed again at the individual level when they are distributed to shareholders as dividends. If a bank has fewer than 100 shareholders and satisfies some other size and complexity criteria, it can organize itself as a Subchapter S corporation. For these banks, profits are not taxed at the corporate level, but they are still taxed at the individual level when they are passed through to the shareholders. Credit unions, in contrast, do not pay any taxes at the corporate level, nor do they pass any tax liability to the owners of the organization, namely the members of the credit union. This favorable treatment may make it more likely for a credit union than a commercial bank to purchase a marginally profitable community bank.

Finally, as noted above, small community banks tend to have deep ties to their customers and take pride in fostering their communities’ growth and financial security. Other things equal, the owners of these banks might prefer to sell to an organization that has similar customer-oriented values. That is, they might feel that they have more in common with the culture at a neighborhood credit union than with the culture of a distant large bank.

Conclusion

Only time will tell whether credit unions will continue to buy banks at an increasing rate. Because of all the regulatory and business-model barriers involved, it will likely never be a dominant transaction type, but there are clearly times when it makes business sense.

Other credit unions will likely study the financial performance of these “early adopters” to determine whether to pursue their own bank deals. If the acquiring credit unions can successfully navigate the different cultures, regulations and business models, and if they can retain enough of the employees and customers, these transactions have the potential to be a win for all the stakeholders involved.

Table 1

| Transaction Date | Buyer | Credit Union Type | Credit Union Assets (in millions) | Name of Acquired Bank | Acquired Entity’s Primary Regulator | Acquired Entity’s Assets (in millions) | Size Ratio of Seller to Buyer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/1/2012 | United FCU | Federal | $1,344.3 | Griffith Savings Bank | FDIC | $85.2 | 6.34% |

| 3/1/2014 | Landmark CU | State | $2,308.8 | Hartford Savings Bank | FDIC | $175.4 | 7.60% |

| 4/1/2014 | Municipal Employees’ CU of Baltimore | State | $1,242.6 | Advance Bank | OCC | $54.2 | 4.36% |

| 6/1/2014 | Five Star CU | State | $258.9 | Flint River NB | OCC | $19.2 | 7.41% |

| 11/1/2015 | Five Star CU | State | $323.9 | Farmers State Bank | FDIC | $44.7 | 13.81% |

| 12/1/2015 | Achieva CU | State | $1,195.2 | Calusa Bank | FRB | $167.3 | 13.99% |

| 5/1/2016 | Avadian CU | State | $645.4 | American Bank of Huntsville | OCC | $107.1 | 16.59% |

| 8/1/2016 | Advia CU | State | $1,218.2 | Mid America Bank | FDIC | $81.3 | 6.68% |

| 8/27/2016 | Royal CU | State | $1,855.6 | Capital Bank | FDIC | $35.4 | 1.91% |

| 3/3/2017 | Family Security CU | State | $587.8 | Bank of Pine Hill | FDIC | $20.1 | 3.42% |

| 6/1/2017 | IBM Southeast Employees’ CU | State | $979.3 | Mackinac Savings Bank FSB | OCC | $111.5 | 11.39% |

| 9/1/2017 | Advia CU | State | $1,437.7 | Peoples Bank | FDIC | $226.6 | 15.76% |

| 4/21/2018 | Lake Michigan CU | State | $5,461.2 | Encore Bank | FDIC | $391.6 | 7.17% |

| 6/15/2018 | Mid Oregon FCU | Federal | $289.1 | High Desert Bank | OCC | $20.3 | 7.03% |

| 8/1/2018 | Georgia’s Own CU | State | $2,342.7 | State Bank of Georgia | FDIC | $96.2 | 4.10% |

| 9/1/2018 | Superior Choice CU | State | $417.5 | Dairyland State Bank | FDIC | $79.8 | 19.11% |

| 9/29/2018 | LGE Community CU | State | $1,296.2 | Georgia Heritage Bank | FDIC | $94.3 | 7.28% |

| 10/1/2018 | Achieva CU | State | $1,743.4 | Preferred Community Bank | FDIC | $115.9 | 6.65% |

| 11/1/2018 | Evansville Teachers FCU | Federal | $1,568.8 | American Founders Bank | FDIC | $88.3 | 5.63% |

SOURCES: The National Information Center (NIC), Reports of Condition and Income for credit unions produced by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), Reports of Condition and Income for insured U.S. banks and thrifts produced by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) and author’s calculations.

NOTE: FDIC, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.; OCC, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; and FRB, Federal Reserve Bank.

Endnotes

- See Dahl et al.

- See Wheelock and Wilson.

- See www.ncua.gov/support-services/credit-union-resources-expansion/field-membership-expansion for further details on the field of membership.

- See www.cuna.org/Advocacy/Priorities/Member-Business-Lending for details.

- Business lending for both types of institutions consists mainly of commercial and industrial loans, agricultural loans, construction and land development loans, loans secured by nonfarm nonresidential property, and loans secured by farmland.

- See Emmons and Schmid.

- See Hui.

- In this way, they are similar to family-owned or otherwise closely held banks, but these small banks often lack the resources to make acquisitions.

- For comparison, the weighted average ROA for all banks under $1 billion in assets from 2012 to 2018 was 1.01 percent.

References

Dahl, Drew; Fuchs, James; Meyer, Andrew; and Neely, Michelle. “Compliance Costs, Economies of Scale and Compliance Performance: Evidence from a Survey of Community Banks.” Working Paper, April 2018. See www.communitybanking.org/~/media/files/compliance%20costs%20economies%20of%20scale%20and%20compliance%20performance.pdf.

Emmons, William; and Schmid, Frank. “Credit Unions and the Common Bond.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Review, September/October 1999, Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 41-64.

Hui, Vincent. “Buying a Bank Is in Line With Growth.” CU Management, March 2018, Vol. 41, No. 3.

Wheelock, David; and Wilson, Paul. “Are Credit Unions Too Small?” Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2011, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 1343-59.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us