Many Countries Sink or Swim on Commodity Prices—and on Orders from China

Many emerging economies—and also those of some developed countries, such as Australia, Canada and Norway—rely heavily on the production of commodities and their sale to global markets. For example, more than 10 percent of Canada's and Chile's output in 2013 could be attributed to the export of commodities, as can be seen in Figure 1. The equivalent share is much higher for Venezuela and other oil-producing countries. The figure also shows the diversity in the mix of commodities produced and exported, as well as some diversity in the ratio of commodities exported as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) across these countries.

In this article, we examine the extent to which the business cycles in emerging countries are highly dependent on fluctuations in the global prices of commodities. As a corollary, we show that the prospects of expansions and contractions for emerging countries are closely linked with the outlook for the countries importing commodities. Additionally, we show how the changing composition of buyers of commodities has made emerging markets increasingly susceptible to the whims of a single buyer: China. Indeed, the recent decline in commodity prices and the slowdown of growth in China go a long way in explaining the recent recessions in Brazil and Canada and may portend further turmoil in many emerging markets.

Commodity Prices and the Business Cycle

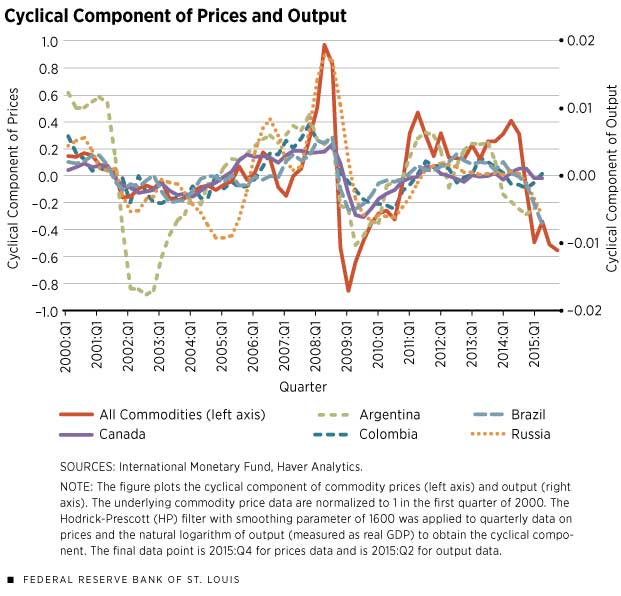

Figure 2 shows the deviations from trend of a weighted index of commodity prices and log output for Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia and Russia for all quarters between 2000 and 2016. This cyclical component of prices and output is obtained by estimating and removing the trend component of each variable.1 The red line shows the cyclical behavior of global commodity prices (left axis). The figure shows that commodity prices exhibited significant volatility over the past 16 years. In particular, between 2000 and 2006, commodity prices were trending upward (not shown in figure) with frequent fluctuations around this trend. The year leading up to the Great Recession saw a dramatic increase in the price of all commodities, led largely by increases in energy prices and in the prices for food and beverages. The global recession saw a sharp decline in all prices, only to display an equally sharp recovery by early 2009. The causes of the dramatic recovery in commodity prices are debatable, but by 2011 they had recovered or exceeded prerecession levels.2 Between 2011 and 2014, commodity prices remained relatively stable in trend with small deviations.

Since the summer of 2014, there has been a sustained drop in commodity prices, most noticeably in energy. Some of the decline in energy prices can be attributed to supply-side factors. In particular, the newfound abundance of energy in the U.S. and resulting fight for market share by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries have led to plentiful supply and falling prices. There is no such obvious supply-side factor that can explain the drop in all other commodity prices, which has attracted much less attention.

The right axis of Figure 2 displays the deviations of output, measured as GDP, from its trend for four emerging market economies and Canada. The figure shows that the cyclical components of output and commodity prices are highly correlated with each other.3 Indeed, the dramatic, fast and sustained recovery in commodity prices must be credited as a major source of the relatively stronger, faster and sustained recovery of emerging markets following the recession, relative to the recoveries in the U.S., Europe, Japan and other major economies.4 Both Figure 1 and 2 make a compelling case for the interlinkages between emerging markets and the prices of commodities: One or two years after the collapse in 2009, a tidal wave in rising commodities prices pushed emerging economies to quickly recover and grow. Nowadays, the tidal wave has receded, and many emerging markets are in danger of capsizing.

The Impact of China

From colonial times a few centuries ago, commodity prices have been driving fluctuations of commodity-exporting economies. What is interesting in this last cycle is the emerging role of China, an emerging economy itself. Strikingly, China—and to a lesser extent India—has surged as an importer of commodities over the past two decades. In 1990, China accounted for only 2 percent of all commodities traded, while the U.S. and Japan accounted for about 15 percent each. By 2013, China was the leading commodity importer, at 15 percent of global trade, while the U.S. and Japan had fallen to 10 percent each. A similar trend holds if we consider only the market for energy commodities, e.g., oil, natural gas and coal. (India displays similar trends, although starting much later: In 2005, India accounted for 1 percent of all global imports of commodities; in 2013, it accounted for 5 percent.)

Some of the rise of China as the top importer of commodities is due to a global shift in manufacturing, which also has manifested in a decline in energy imports into the U.S. and slow growth in Japan. Moreover, since the early 2000s, the U.S. has increasingly relied on domestic energy sources, lowering its need for energy imports, while Japan's "lost decade" led to a decline in trade. However, China's annual GDP growth rate averaged about 10 percent between 1990 and 2013, and this high growth rate was accompanied by an ever-growing demand for industrial inputs. Indeed, China's growth was shared by many emerging economies as they provided the exports to sustain China's surge. But these same economies must also share in China's slow-growth periods. Recently, China's growth rate has fallen to about 6 or 7 percent (still high compared with that of the U.S. and other developed countries today), and the uncertainty around Chinese growth has increased. All of these factors are behind the recent collapse in commodities prices.

Conclusion

It is striking how strongly commodities prices drive the overall economic fluctuations of emerging countries despite remarkable differences in their composition of commodities for export and their total export shares as a percentage of their GDP. Yet, for these countries a salient common factor emerges: the importance of China and its growth prospects.

Endnotes

- These deviations are computed using the Hodrick-Prescott filter, the most common method to separate business cycle components from long-run trends. [back to text]

- See Fawley and Juvenal. [back to text]

- The values for the coefficient of correlation of output and prices for all the emerging economies are positive and above 0.50, ranging from 0.51 for Argentina to 0.80 for Brazil. [back to text]

- See Helbling. [back to text]

References

Fawley, Brett; and Juvenal, Luciana. "Commodity Price Gains: Speculation vs. Fundamentals." The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' The Regional Economist, July 2011, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 4-9.

Helbling, Thomas. "Commodities in Boom." International Monetary Fund's Finance and Development, June 2012, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 30-31.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us