Banks and Credit Unions: Competition Not Going Away

See end of article for a clarification on the tax treatment of Subchapter S corporations.

The U.S. financial system includes depository institutions small and large, some chartered by states and others by the federal government, some operated for profit and others not for profit, some operated by volunteers and others by the world's foremost financial professionals. Credit unions and commercial banks are important parts of this system—and aggressive competitors. Both types of institutions are chartered by the federal and state governments, often with the intent of fostering competition between the institutions. At the same time, a web of regulations seeks to maintain competitive balance between the institutions. In this essay, we examine aspects of these regulations and the competition between credit unions and banks since the 1998 Credit Union Membership Access Act (CUMAA) relaxed membership regulations for credit unions.

At the end of September 2012, approximately 2,710 credit unions were chartered by 47 states and Puerto Rico, and approximately 4,320 credit unions were chartered by the federal government. Each is a not-for-profit cooperative, democratically governed (with each member having one vote) and operated by a volunteer board of directors elected by the credit union's members. Credit unions had 96 million members, representing more than half of American families, and provided 16.7 percent of outstanding consumer credit.1 Credit unions have become important in home-mortgage and small-business lending, too.2

In the provision of financial services to households, credit unions and community banks continue to grow more similar, a trend that began with advances in technology during the mid-1970s and accelerated during the 1980s.3 Because most credit unions offer a full range of financial products and services (either directly or through third parties), a number of news articles have suggested that households consider larger credit unions as full-service alternatives to banks.4 Academic studies have confirmed that (1) rates on deposits at banks and credit unions move together, (2) credit union lending to small businesses partly displaces bank lending, and (3) credit union lending has been steadier through business cycles, including the recent financial crisis, than bank lending.5 Further, a series of studies have concluded that during 1989-2001 the presence of one or more credit unions in a county tended to reduce the number of banks and competition among the existing banks.

In any industry where firms compete, each asks if others have an unfair advantage. Banking industry supporters have long asserted that credit unions possess an advantage because they are exempt from federal income tax. State-chartered credit unions became exempt in 1917, federal credit unions in 1935. Although the exemption reduces credit unions' cost of capital by approximately 40 percent relative to a fully taxed environment, several thousand small and medium-size banks are organized for tax purposes as Subchapter S corporations and are similarly exempt from federal income taxes.6

Congress has been clear regarding the social purpose of the credit union exemption: "Credit unions are exempt from federal taxes because they are member-owned, democratically-operated, not-for-profit organizations generally managed by volunteer boards of directors and because they have the specified mission of meeting the credit and savings needs of consumers, especially persons of modest means." 7

The words "modest means," not defined by Congress, often have been interpreted as synonymous with lower- and middle-income wage earners. Banking industry supporters argue that banks serve larger numbers of low- and middle-income households and that the exemption is a taxpayer subsidy that encourages credit union expansion. Credit union advocates argue (1) that the banking industry serves more low-income customers because it is larger, (2) that credit unions should not turn away eligible higher-income persons who wish to be members, and (3) that banks can issue equity to raise capital, while credit unions cannot.

A 2006 study of 14 million credit union members concluded that the distribution of their incomes closely resembled the income distribution of the nation as a whole.8

When the dust settles, the core issue is whether the tax exemption tilts the competitive balance toward credit unions and away from community banks. The intensity of feeling is illustrated by the longevity of the issue. In 1997, the first vice president of the American Bankers Association (ABA), R. Scott Jones, testified at a House of Representatives hearing: "The fact is that the extension of a single common bond to multiple common bonds carries with it an extension of government benefits and special regulatory treatment, paid for by all taxpayers. In fact, if credit unions were not subsidized by the government, I doubt that we would be here this morning." In January 2013, the chairman of the ABA, Matt Williams, placed first on his 2013 "wish list" an end to the credit union federal tax exemption.

There is precedent for removal of a federal tax exemption: Mutual savings banks and savings and loan associations (similar to credit unions in being owned by their depositors but dissimilar in not being organized as cooperatives) were exempt from federal income taxes until 1952, when Congress ruled that the nature of their business had matured to the extent that they should be taxed in the same manner as commercial banks.

Credit Unions and the Banking Industry

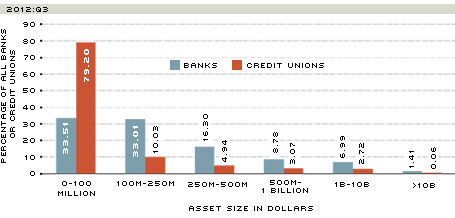

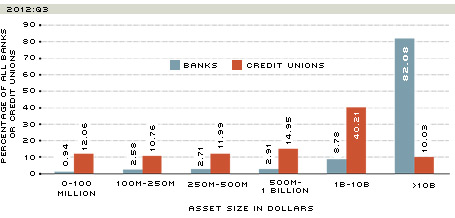

Credit unions compete primarily with community banks, those banks with assets of $10 billion or less. At the end of September 2012, although the nationwide numbers of credit unions and all commercial banks were approximately equal (7,030 for credit unions and 6,170 for all banks), credit unions in the aggregate held $1 trillion in assets and banks held $13 trillion. Most credit unions and banks are small: At the end of last September, 97 percent of credit unions and 91.5 percent of banks held less than $1 billion in assets (Figure 1). Further, about 50 percent of the credit union industry's assets but only 10 percent of the banking industry's assets were held by small institutions—those with less than $1 billion in assets.

Distribution of Number of Banks and Credit Unions, by Assets Held

SOURCES: Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., National Credit Union Administration, authors' calculations.

Distribution of Assets of Banks and Credit Unions, by Assets Held

SOURCES: Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., National Credit Union Administration, authors' calculations.

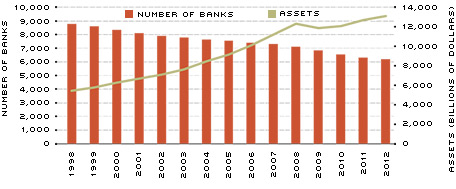

Commercial Banks: Number and Assets

SOURCE: Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

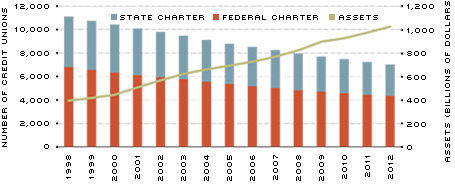

Credit Unions: Number and Assets

SOURCES: Credit Union National Association, National Credit Union Administration.

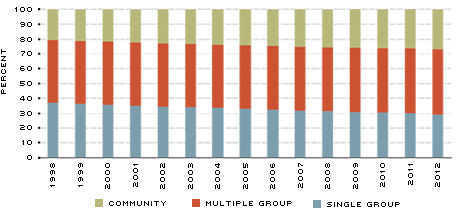

Share of Federally Chartered Credit Unions, by Charter Type

SOURCE: National Credit Union Administration.

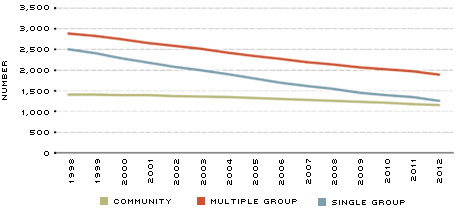

Number of Federally Chartered Credit Unions, by Charter Type

SOURCE: National Credit Union Administration.

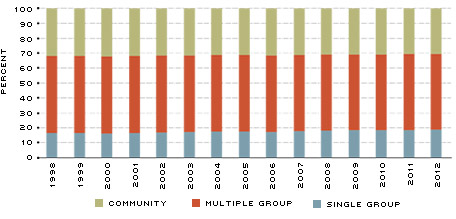

Share of Assets of Federally Chartered Credit Unions, by Charter Type

SOURCE: National Credit Union Administration.

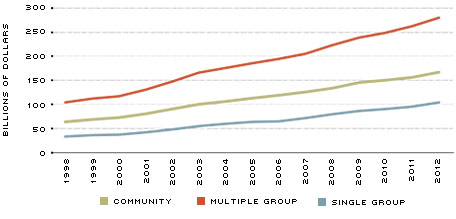

Amount of Assets of Federally Chartered Credit Unions, by Charter Type

SOURCE: National Credit Union Administration.

During the past 15 years, the banking and credit union industries have experienced remarkably similar trends (Figure 2). For example, the number of banks has decreased 30 percent, while total assets have increased 140 percent. The number of credit unions has decreased 36 percent, while total assets have increased 160 percent.

Field of Membership and the Common Bond

Membership in a credit union is governed by its "field of membership" (FOM). Each FOM is composed of one or more groups of persons who share a "common bond." Examples include an occupational bond (the same employer), an associational bond (membership in the same organization or association) and a community bond (residence in the same neighborhood, community or rural district).9 Although statutes vary, most state credit unions operate with multiple-group FOMs. Prior to 1982, federal regulations permitted only single-group FOMs for federally chartered credit unions. In 1982, federal regulators first allowed FOMs that included more than a single occupational or associational group; in 1983, they permitted FOMs for individual credit unions that included both occupational and associational groups.10 More recently, in circumstances where a solvent credit union has acquired an insolvent one, federal regulators have permitted FOMs that include mixtures of groups with occupational, associational and community bonds.

In 1990, the American Bankers Association and its supporters sued federal regulators, asserting that federal law did not permit multiple-group FOMs. Although the plaintiffs prevailed in the Supreme Court on Feb. 25, 1998, Congress quickly vacated the court's action: On Aug. 7, 1998, President Clinton signed the Credit Union Membership Access Act, which amended federal law to explicitly permit multigroup FOMs. But the law had a number of caveats. First, only groups with fewer than 3,000 members would be allowed to join existing credit unions (except when regulators certified that the group was unlikely to form a viable separate credit union). Second, community charters were restricted to a "well-defined local community, neighborhood or rural district." Third, a credit union's commercial lending could not exceed 12.25 percent of its assets.

On Jan. 8, 1999, the ABA again sued federal regulators, alleging that their rules with respect to occupational and associational groups did not reflect Congress' intent.

The suit was dismissed by the U.S. Court of Appeals.

Later litigation challenged the community bond. In March 2003, federal regulators approved a community charter in Utah that included six counties, two metropolitan statistical areas (Salt Lake City and Ogden) and, as noted by the court, two mountain ranges. The ABA sued the next year. The District Court vacated approval of the community charter for lack of adequate procedure but not because of the merits. The community charters were revised and approved.

As of 2012, there were three criteria for a federal community FOM. First, the area must have clear geographic boundaries, such as a city, township, county or counties, or school district; entire states and congressional districts are not permitted. Second, there must be interaction among the residents, such as a single political/governmental jurisdiction or designation of the area by the federal Office of Management and Budget as a Core Based Statistical Area (or a Metropolitan Division within a Core Based Statistical Area). Third, the area must have a population of no more than 2.5 million people.11 State criteria for community charters may differ.

See Figure 3 for more data on credit unions with federal charters.

Credit Union Expansion

Since January 1999, multiple-group federal credit unions have added 151,000 groups that contained 29 million persons at the time they were approved. Of the 151,000 groups, 89 percent contained 200 or fewer people, while 806 groups contained at least 3,000 people.

The largest groups were large indeed. In 2005, the Georgia United Federal Credit Union added the 367,000 employees of the Catholic archdiocese of Atlanta. In 2006, South Florida Educational Federal Credit Union added the 370,000 students attending Miami-Dade public schools. In 2007, the Pentagon Federal Credit Union added the 300,000 persons in the Military Officers Association of America. In 2012, Logix Federal Credit Union (Los Angeles) added 325,000 members of the California Teachers Association.

Because some multiple-group associational credit unions include in their FOM certain professional, social and civic associations that accept anyone as a member, the number of their potential members is limited only by the U.S. population. The Pentagon Federal Credit Union, for example, includes several associations that offer membership to anyone for a nominal fee.12 At New Jersey's Affinity Federal Credit Union, for a one-time $25 fee, any resident of New York, New Jersey or Pennsylvania can join the New Jersey Coalition for Financial Education and become a member of the credit union.13 Utah's HeritageWest Credit Union offers membership to all people who contribute $10 or more to the We Promise Foundation of its parent, the Chartway Federal Credit Union, based in Virginia Beach, Va.

Perhaps the most-recent creative example of FOM expansion is the decision in 2012 by Thrivent Financial for Lutherans, a Minnesota financial holding company, to split its Thrivent Financial Bank into two parts: an associational federal credit union and a trust company, the latter to remain a subsidiary of the holding company. A writer in the Credit Union Times noted that offering loan products and other retail banking services through the tax-exempt credit union would allow Thrivent to reduce prices while continuing to offer investment products through its sister trust company. But what of the common bond? Membership in the credit union is open to members of Thrivent Financial for Lutherans, a mutual organization. As of this writing, Thrivent Financial for Lutherans' web page offers for $19.95 an "associate" membership to any person who "provides support for strengthening the membership efforts of Thrivent Financial for Lutherans." The membership requires no purchase of products or services—but the web page notes, "The $19.95 annual membership fee may be waived when you purchase a product from a Thrivent Financial affiliate or subsidiary, such as a Thrivent mutual fund product or Thrivent Federal Credit Union product." With the waiver, this credit union is, perhaps, the lowest-cost open-to-anyone associational credit union in the United States.

In addition, some federal credit unions operate in multiple states. Noteworthy are the $6.9 billion Security Service Federal Credit Union, San Antonio, Texas, with 70 locations in three states, and the aforementioned Chartway, with 64 offices in 10 states. These credit unions, with complex FOMs, were created when federal regulators used broad emergency authority to enable the purchase and assumption of an insolvent credit union by a solvent one. Under this authority, the acquirer and acquired credit unions may be in different states, and the acquirer may retain the FOMs of the acquired in addition to its own.

Finally, we note that three federal credit unions bought assets from banks during 2012. One of the more closely watched was the purchase by GFA Federal Credit Union (a community charter) in Gardner, Mass., of Monadnock Community Bank in Peterborough, N.H., a shareholder-owned savings bank.14 At the outset, some analysts believed that it would be difficult for a credit union with a federal community charter to purchase a bank 25 miles away. That difficulty seems to have been resolved—but perhaps at the expense of credit unions further resembling banks.

Summary

Have the combined effects of the exemption from federal income taxes plus the multigroup expansion possibilities permitted by the CUMAA tilted the competitive balance away from banks and toward credit unions? The evidence does not permit any sharp conclusions. Despite the often-heated rhetoric of competing advocates, both industries have experienced similar trend growth since 1998. Further, the relative proportions of assets held by federally chartered single, multiple and community bond credit unions have changed little. The only safe prediction is that, in the future, credit unions and community banks will continue to grow more similar.

Editor's Note, posted on July 19, 2013:

We received comments from several readers regarding a statement appearing in this article. The article states that credit unions and Subchapter S corporations are "similarly exempt" from federal income taxes. We asked Julie L. Stackhouse, senior vice president of the St. Louis Fed's Banking Supervision and Regulation division, to clarify the tax treatment of Subchapter S corporations. Her comments are below:

A Subchapter S corporation is a corporation that has between one and 100 shareholders and that passes through net income or losses to shareholders in accordance with Internal Revenue Code, Chapter 1, Subchapter S. Subchapter S election is subject to criteria beyond restrictions on number of shareholders, including limitations on the class of permissible stock (only one class is allowed) and on who may be an eligible shareholder. There is no guarantee of dividends from the Subchapter S corporation to its shareholders for purposes of paying tax liability.

Because of these limitations, most commercial banks are organized as typical C corporations. Earnings of a C corporation are first taxed at the corporate level and then again at the shareholder level when dividends are paid on those earnings.

Credit unions, in contrast, do not pay taxes at the corporate level, nor do they have an outstanding tax liability that is passed through to their members.

In summary, Subchapter S corporations avoid the double taxation experienced by C corporations and their shareholders. However, these advantages do not amount to an exemption from federal taxation.

Endnotes

- Federal Reserve System, Flow of Funds data and authors' calculation. [back to text]

- See Smith and Woodbury; Wilcox; Smith. [back to text]

- See Feinberg and Rahman. [back to text]

- For example, Browning, Lieber and Prevost. [back to text]

- See Burger and Dacin; Smith and Woodbury; Smith. [back to text]

- See Credit Union National Association. [back to text]

- See U.S. 105th Congress. [back to text]

- See National Association of State Credit Union Supervisors. [back to text]

- See Emmons and Schmid (1999 and 2003). [back to text]

- See Burger and Dacin. [back to text]

- See National Credit Union Administration. [back to text]

- See Lieber. [back to text]

- See Browning. [back to text]

- See Silver-Greenberg. [back to text]

References

Browning, Lynnley. "Credit Unions Expand Their Clientele." The New York Times, Sept. 24, 2010.

Burger, Albert E.; and Dacin, Tina. "Field of Membership: An Evolving Concept." Filene Research Institute, Madison, Wis., 1992.

Credit Union National Association. CUNA Issue Summary: Subchapter S Corporation Bank, February 2013.

Emmons, William R.; and Schmid, Frank A. "Credit Unions and the Common Bond." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' Review, September/October 1999, Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 41-64.

Emmons, William R.; and Schmid, Frank A. "Credit Unions Make Friends—but Not with Bankers." The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' The Regional Economist, October 2003, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 4-9.

Feinberg, Robert M.; and Rahman, A.F.M. Ataur. "Are Credit Unions Just Small Banks? Determinants of Loan Rates in Local Consumer Lending Markets." Eastern Economic Journal, Fall 2006, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 647-59.

Lieber, Ron. "Credit Unions Are Beckoning with Open Arms." The New York Times. June 18, 2010.

Morrison, David. "Thrivent Switches to Credit Union Charter." Credit Union Times, Dec. 5, 2012.

National Association of State Credit Union Supervisors. NASCUS Survey of the State Credit Union System. (Arlington, Va.). 2007.

Prevost, Lisa. "The Credit Union Alternative." The New York Times, Dec. 13, 2012.

Silver-Greenberg, Jessica. "Small Banks Shift Charters To Avoid U.S. as Regulator." The New York Times, April 2, 2012.

Smith, David M. "Commercial Lending during the Crisis: Credit Unions vs. Banks." Filene Research Institute, Madison, Wis., 2012.

Smith, David M.; and Woodbury, Stephen A. "Withstanding a Financial Firestorm: Credit Unions vs. Banks." Filene Research Institute, Madison, Wis., 2010.

U.S. 105th Congress. Bill H.R. 1151 (Credit Union Membership Access Act), March 30, 1998.

Wheelock, David C.; and Wilson, Paul W. "Are Credit Unions Too Small?" Review of Economics and Statistics, 2011, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 1,343-59.

Wilcox, James A. The Increasing Importance of Credit Unions in Small Business Lending. Small Business Administration. Office of Advocacy. Washington, D.C., September 2011.

Williams, Matt. "A Banker's Thoughts on New Year's Resolutions." ABA Banking Journal, January 2013, Vol. 105, No. 1, p. 4.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us