The Trade Collapse: Lining Up the Suspects

Along with the spread of the financial crisis that began in 2007, the world experienced the largest recession since the Great Depression. According to the International Monetary Fund, world GDP fell by 0.8 percent in 2009, while advanced economies experienced a contraction of 3.2 percent, the largest decline in the past 50 years. Exports from the advanced economies fell even more, by a staggering 12.3 percent, about four times as much as the drop in GDP and approximately as much as exports to the advanced economies.

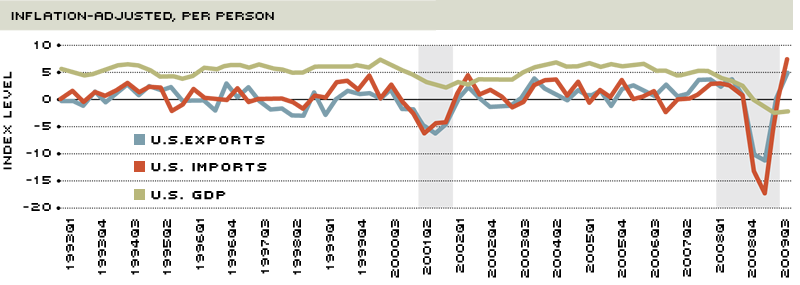

The figure shows the rate of growth of U.S. GDP, imports and exports, as well as a pattern that was common to many other countries during the crisis: The imports and exports of advanced, emerging and developing economies fell by similar percentages, ranging from a minimum of 11.7 percent to a maximum of 13.5 percent. Similarly, the rebound of U.S. trade flows that appears in the figure at the end of 2009 was observed in other countries.

The larger-than-expected drop in trade has puzzled economists and commentators throughout the current recession. A number of trade scholars are looking into potential culprits.

The suspect that can be easily discarded is trade restrictions. Unlike during other recessions and the Great Depression, countries have not used trade measures—such as tariffs, quotas or anti-dumping measures—during this recession to restrict imports. One reason is the World Trade Organization forbids these measures; another reason is we now understand that trade restrictions worsened the Great Depression.

The remaining causes for the plummet in exports are more difficult to discard: the collapse of trade finance, the increase in vertical specialization and the composition of trade flows. Traditional textbook analysis of trade dynamics during recessions attributes trade decline to lower demand for final good imports in the country experiencing a contraction. However, the changes in the way trade is financed and organized, along with a better understanding of the international economy, induced economists to focus on the three elements we discuss here.

First Suspect: Finance

Various studies have documented the importance of finance for international trade transactions, as financial institutions are key suppliers of services such as the evaluation of counterparty default risk and the provision of payment insurance and guarantees to exporters. Economist Marc Auboin estimated that about 90 percent of international trade transactions rely on one form or another of trade finance.

Therefore, the conjecture is that the credit crunch may have caused the large decline in world trade by reducing firms' access to finance. A study by economists Mary Amiti and David Weinstein has shown that a similar mechanism was at work during the Japanese crisis of the late 1990s and early 2000s. They found that lack of financing accounted for nearly one-third of the plunge in Japanese exports during the 1990s.

Fresh evidence for the current recession is hard to come by and to date exists only for exports to the U.S. Economists Davin Chor and Kalina Manova found that countries with tighter credit availability during the crisis exported less to the U.S. Moreover, exports to the U.S. contracted more in sectors that other research has shown to be more heavily dependent on extensive external financing. This early evidence suggests that the trade finance nexus seems to be one of the explanations of the trade contraction during the current crisis, at least for the U.S.

Second Suspect: Vertical Fragmentation

The second suspect is vertical fragmentation, a form of international trade that has been growing exponentially with the spread of globalization in the past 20 years. We normally think of international trade as being dominated by final goods, those that do not need further processing. On the contrary, the data show that international trade in industrialized countries is dominated by capital goods (such as machinery) and other types of intermediate goods (such as steel) that are normally used for the production of consumer goods. In the case of the U.S., these intermediate goods account for nearly three-fourths of total imports and exports.

As massive freighters have minimized the cost of transport, international sharing of production has increased. Goods are increasingly manufactured in stages in different countries. Before a product is completed and shipped to its final destination, its components have often crossed borders several times.

Consider the example of the iPhone. Its CPU and video processing are made in Singapore. Its digital camera, circuit boards and metal casings are made in Taiwan. Its touch-screen controllers are made in the U.S. From these countries, all components are then shipped and assembled in Shenzhen, China, before being delivered to final consumers in various countries. Complete iPhones arrive to American consumers after the phones' components have crossed at least four borders, including the U.S. border twice.

If the demand for final goods declines, the first effect is that the demand for intermediate goods suffers in each of the countries in which production takes place. At the same time, international trade also appears to suffer more than GDP because at each border crossing the full value of the partly assembled good is recorded as trade, while GDP measures only value added. In order to understand the difference, consider a simple good like a pencil, made of two components, wood and graphite, assembled using labor. When the pencil is produced entirely in the U.S., its contribution to U.S. GDP is the final price to consumers (say $1) net of the cost of its components (80 cents); therefore, 20 cents of value has been added. When the pencil is only assembled in the U.S. but its components are imported from Canada, for example, and demand for pencils in the U.S. falls by one unit, U.S. GDP falls by 20 cents, but U.S. imports from Canada fall by 80 cents, four times as much! This happens because GDP is a value-added measure while trade is a gross measure.

Economist Caroline Freund estimates that when world income increases by 1 percent these days, trade increases, on average, by 3.5 percent. In the 1960s, the impact of an equivalent change in income on trade was only 2 percent. This is likely related to the increase in vertical specialization. Various other economists have provided evidence that the recent decline in trade is stronger in sectors that make intense use of intermediate inputs.

Third Suspect: Compositional Effect

During recessions, consumers and firms demand fewer goods; however, the decline in demand is less than equal across all industries because some sectors are more impacted than others. When households and firms adjust their spending downward, the demand for both domestic and imported goods falls. Now, if international trade is concentrated in the sectors that are most impacted by the negative economic shock, then overall trade should experience a greater fall than GDP. For example, consider the case in which overall U.S. GDP declines by 2 percent, but the agricultural component of GDP falls by, say, 7 percent. If trade is particularly concentrated in agriculture, then we would observe a drop in trade larger than the drop in overall GDP.

The composition of the decline in demand may affect the magnitude of the decline in trade simply because there may be more trade in the sectors that were hit the hardest. Economists Andrei Levchenko, Logan Lewis and Linda Tesar show that this is exactly what happened to the U.S. during the current recession; the largest declines in trade are recorded for those sectors that had the largest drops in output (industrial supplies and materials, computers, peripherals and parts, automotive vehicles, engines and parts). This may also explain why international trade in services other than finance, transport and tourism fell by much less than overall trade, as the service component of GDP fell much less than overall GDP during the crisis.

A One-Time Thing?

The international economy operates as a network in which the line between producer and consumer continues to zig-zag and blur. In such a world, it is key to recognize those factors that have the most influence on international trade. Economists have identified three main suspects as the leading causes of declining trade volumes during the current recession and, by lining up the suspects, they have been able to analyze the causes' individual contributions to the trade collapse, at least for the U.S. As new data from the current crisis become available, other countries will be studied in order to help us understand whether the large drop in trade is specific to this recession or will likely reappear in future recessions. In the meantime, most projections for this year indicate a recovery in world GDP (3.9 percent in the World Economic Outlook of the International Monetary Fund) and in world trade (a robust 5.8 percent increase).

Growth Rates

SOURCE: Authors' calculations based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

References

Auboin, Marc. "Boosting Trade Finance in Developing Countries: What Link with the WTO?" Working Paper ERSD-2007-04, World Trade Organization, November 2007.

Amiti, Mary; and Weinstein, David. "Exports and Financial Shocks." Working Paper 15556, National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2009.

Borchert, Ingo; and Mattoo, Aaditya. "The Crisis-Resilience of Services Trade." Working Paper 4917, the World Bank, April 2009.

Chor, Davin; and Manova, Kalina. "Off the Cliff and Back: Credit Conditions and International Trade during the Global Financial Crisis." Stanford University Manuscript, December 2009.

Coughlin, Cletus. "World Trade: Pirated by the Downturn." Federal Reserve Bank of

St. Louis International Economic Trends, August 2009.

Economist, The. "The Collapse of Manufacturing." Feb. 21-27, 2009, p. 9.

Freund, Caroline. "Demystifying the Collapse in Trade." VoxEU.org, July 3, 2009.

See www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/3731

Levchenko, Andrei; Lewis, Logan; and Tesar, Linda. "The Collapse of U.S. Trade: In Search of the Smoking Gun." VoxEU.org, November 27, 2009. See www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/4280

World Trade Organization. "WTO Sees 9% Global Trade Decline in 2009 as Recession Strikes." (Press release from March 24, 2009.) See www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres09_e/pr554_e.htm

Yi, Kei-Mu. "The Collapse of Global Trade: The Role of Vertical Specialisation," in Richard Baldwin and Simon Evenett, eds., The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis: Recommendations for the G20. Pp. 45-48. An e-book from VoxEU.org, March 2009. See www.voxeu.org/

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us