Community Profile: Image Makeover—Starkville Shows There's a Place for High Tech in Mississippi

|

|

|

Starkville, Miss., |

|

| Population | 21,869 |

| Labor Force | 21,692 |

| Unemployment Rate | 3.5% |

| Per Capita Income | $18,799 |

| Top Five Employers | |

| Mississippi State University | 4,200 |

| Service Zone (customer relationship management) | 650 |

| School District | 600 |

| Wal-Mart | 480 |

| Gulf States Manufacturers Inc. (fabricated metal products) | 400 |

| NOTES: Population and per capita personal income are from 2000. Other data is from October 2002. Labor force, unemployment rate and per capita personal income numbers pertain to all of Oktibbeha County. | |

“I don’t want to become Mississippi.”

This jab at the Magnolia State was spoken by Texas Gov. Rick Perry as he addressed reporters in January about his state’s tight budget conditions.

Frequently maligned for ranking at or near the bottom in areas like education, transportation and job growth, Mississippi has grown accustomed to disparaging comments such as Perry’s. For years, states coping with their own problems have taken comfort in the words: “It could be worse. We could be Mississippi.” But there are plenty of residents who no longer wish to put up with the put-downs. Many of them live in Starkville, where the assets of Mississippi State University (MSU) are helping to bury common stereotypes.

“There is often a negative image of Mississippi,” says David Thornell, president and CEO of the Greater Starkville Development Partnership. “Around here, we have to prove that it’s just an image. It’s not reality. We do have a progressive community that would be a good home for progressive businesses.”

Adds Starkville Mayor Mack Rutledge, “We feel that our future is in high technology, which would grow out of the expertise at MSU.”

Progress at the Park

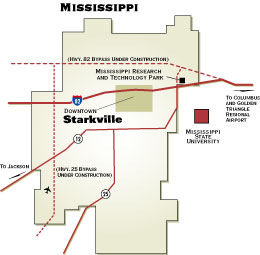

Reasons for the mayor’s optimism are easily traced to the Mississippi Research and Technology Park. Situated on 220 acres near the university, the park is a joint venture of the city of Starkville, Oktibbeha County and the university. Ground has been broken or will soon be broken for three critical projects at the park:

1. The Ralph E. Powe Center for Innovative Technology: When this 25,000 square-foot small-business incubator is completed this November, it will replace the 3,000 square-foot Golden Triangle Enterprise Center, also located in the park.

“The current incubator is 95 percent filled, and we keep getting requests for space that we don’t have,” says Marc McGee, vice president of property development and research at the Development Partnership.

The anchor tenant in the Powe Center will be SemiSouth Laboratories, a maker of silicon carbide chips. The company will operate in what’s called a clean room, an area that filters out airborne particles so that lab specimens can be kept in a sterile environment.

Another high-tech company, MPI Software Technology Inc., was one of the first businesses to move into the incubator in 1996. A developer of software for high performance computing, MPI outgrew the incubator in 1999 and bought a former bank building on Main Street downtown. The company employs 25 people locally.

MPI began as a spin-off of research at MSU by Anthony Skjellum, who still teaches computer science at the university. He and his wife, Jennifer, run the company, which has won several awards, including the Small Business Administration’s Roland Tibbetts Award for technology excellence. The Skjellums credit the incubator program with helping them survive the start-up years before they were able to graduate from the facility.

Among MPI’s clients today is the MSU Engineering Research Center (ERC), also located at the technology park. The center is home to one of the top 20 academic supercomputing clusters in the United States. Research at the ERC is supported by many agencies, including the National Science Foundation, NASA, the Department of Defense and the Department of Transportation.

2. The Center for Advanced Vehicular Systems (CAVS): This center is one of six research organizations at the ERC, but the only one that will have its own building when completed this fall. Using resources from the university’s industrial and mechanical engineering departments, CAVS will work closely, though not exclusively, with Nissan to perform automotive tests through the use of computer models. The Japanese automaker is opening a production plant in Canton, Miss., this year. By eliminating the need to build full-scale models for testing, automakers like Nissan will be able to shorten the process from conception to production.

“Doing all that work computationally saves a lot of time and money,” says Wayne Bennett, dean of engineering at MSU.

3. Viking Range facility: Greenwood, Miss., 85 miles west of Starkville, is the headquarters for Viking Range, a leading manufacturer of kitchen appliances. The company will begin construction this spring on a product development and research facility. Viking Range expects to employ 35 people at the site upon its completion in 2004.

“For Viking Range, we’re able to locate our facility close to a university with a great engineering school,” says Dale Persons, a spokesman for the company. “For the university, it will allow a place where professors can do hands-on research and students can do co-ops in a real business world atmosphere.”

|

| Students and faculty at Mississippi State University's Engineering research Center perform research and develop applications for both government and industry. |

|

| Mississippi State University is Starkville's leading employer and home to more than 16,000 students. |

Engineering a Bright Future

A running theme in all of these projects is MSU’s engineering school. Make that the just-renamed James Worth Bagley College of Engineering— emphasis on “Worth.” Bagley last year presented his alma mater with a $25 million endowment, the largest gift in Mississippi State’s history. Bennett says Bagley’s gift will “provide the resources needed to take our college to national prominence.”

Bennett points out that one out of every eight students at Mississippi State is an engineering student. He adds that in 2002 the college enjoyed a 26.5 percent increase in research expenditures, which he expects will move the school into the top 30 in research out of 322 engineering schools nationwide. These statistics, combined with the lure of the engineering school’s resources to prospective businesses, leads Bennett to declare: “We play a key role in the economic development of this region and the entire state.”

The momentum at both the technology park and the engineering school should counter the region’s problems with “brain drain,” as explained by Melvin Ray, special assistant to the university president: “We educate students; they’re technology savvy; and then they’re recruited to other states that end up competing against us. But now, we should be able to keep more of those bright young students here as employees with high-paying jobs.”

Bennett agrees: “We’re stemming the brain-drain tide. One of the first things a technology-based company looks for in an area is whether it can get the technical manpower it needs.”

Choppers Ahead

Starkville and the rest of the Golden Triangle region—which includes the cities of West Point and Columbus—landed an important chunk of business last year when American Eurocopter Corp. announced it will build a 100,000 square-foot helicopter assembly and manufacturing plant. A subsidiary of Eurocopter, the largest helicopter manufacturer in the world, American Eurocopter will build on 40 acres at the Golden Triangle Regional Airport.

Airport Executive Director Nick Ardillo led the multicommunity effort to bring American Eurocopter to the area. The company, he says, picked the Golden Triangle from an original list of 25 Mississippi communities.

“We had lost several low-tech manufacturing plants over the past couple years,” says Ardillo. “So the region really needed this positive hit.”

Ardillo says a key factor in the area’s bid was the aeronautical engineering expertise at the Raspet Flight Research Lab at MSU. American Eurocopter will employ about 100 in the beginning.

Mayor Rutledge says: “One of the things that makes our eyes light up is the possibility that they may expand. That’s what makes us feel that this was such a significant coup.”

Attracting more retail dollars to Starkville would be another coup, Rutledge says. “Sales tax is our main source of revenue, and that’s something that we’re trying to grow, but it’s not growing fast enough. We haven’t yet become recognized as a regional shopping center.”

Rutledge cites surrounding communities in the state like Tupelo, Columbus and Meridian that offer more attractive retail opportunities. He believes that help is coming in the form of a series of road construction projects underway. These include a State Road 25 bypass, to be completed this spring, and a U.S. 82 bypass and State Road 12 extension, each scheduled to be completed in spring 2004.

If the economy improves once these roads are all completed, Rutledge expects a major upswing in Starkville’s commercial and industrial growth.

“It’s going to be like a rocket around here because we’ll be better situated to capitalize,” he says.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us