The Pitfalls of Industrial Policy

"The problem is that in economics two wrongs do not make a right."

—Paul Krugman, Economist, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Krugman's observation about economics would ring true in any number of economic policy debates. But it is especially appropriate in the current debate on whether the United States needs an industrial policy. Faced with increasing global competition and government activism abroad, many U.S. business interests have been calling on the federal government to take a more active role in the U.S. economy. Right now, Washington seems inclined to listen.

While there is no formal definition of industrial policy, it usually refers to a set of policies designed to promote promising industries while propping up or easing the fall of declining industries. Defined that way, industrial policy is often described as the government picking winners and losers. Implicit in the argument for a U.S. industrial policy is the belief that market forces alone cannot or will not produce economic growth and rising living standards.

Proponents of industrial policy offer two propositions to support their cause. The first is that the United States is deindustrializing and becoming less competitive in world markets. They argue that the country has lost much of its manufacturing base and is no longer at the cutting edge in newer, high-technology industries. The government, proponents say, needs to step in and promote the development of new technology with commercial possibilities and retrain workers displaced in declining industries.

The second proposition is that other countries—especially Japan—have successfully enacted policies to promote new industries and protect older, less profitable, but essential industries. Thus, the United States is losing not only through its inaction but also as a result of successful market interventions by competing nations. The pervasive belief is that the United States must emulate these countries to maintain its economic superpower status.

Flawed Foundations

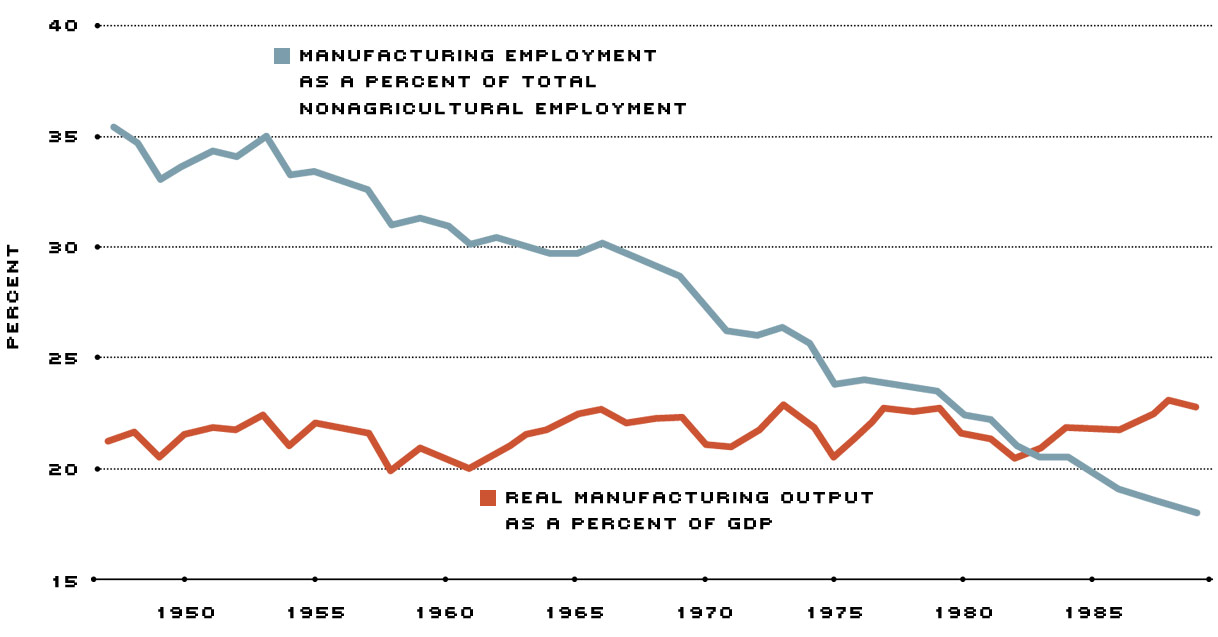

According to economist Charles Schultze, both propositions are flawed. First, he says, the United States is not deindustrializing. Those who make this argument point to the relative decline in U.S. manufacturing workers since World War II and the absolute decline in manufacturing workers during the 1980s; what they ignore is that manufacturing output as a percent of gross domestic product has remained relatively constant, as both have grown at roughly the same rates (see chart).

Manufacturing Productivity: Making More With Less

The portion of U.S. workers in manufacturing has steadily declined in the postwar era. Today, about one in five workers is employed in the manufacturing sector compared with one in three at the end of WWII. Despite this decline, manufacturing output as a share of total output has remained fairly constant, around 20 to 23 percent. What this demonstrates is a significant improvement in manufacturing productivity.

The bottom line is that the nation is producing more goods with fewer workers. During the 1980s, U.S. manufacturing productivity rose 2.9 percent per year. This is good news from an economic standpoint because it means resources are being freed up for other productive activities. While the adjustments of workers in old industries to new positions can be painful initially, increasing productivity benefits the economy as a whole, setting the stage for increased growth and efficiency.

Moreover, the notion that industrial policy is primarily responsible for economic success in Japan is disputable. While Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) does direct investment to certain sectors and industries, these investments do not always pay off. Steel and oil—two of the many industries that have received financial support from MITI—are largely viewed as a drag on the Japanese economy. Some of MITI's past initiatives, had they been successful, would have proved very foolish for Japan: MITI actively discouraged Honda from getting into the automobile business and Sony from getting into the consumer electronics business.

If industrial policy was not responsible for Japan's economic strength in the postwar period, what was? Much of Japan's early postwar growth was simply recovery from near total destruction. After that, the evidence points to Japan's macroeconomic policies and business practices. In the 1960s and 1970s, Japanese economic policies encouraged private savings, which were channeled into investment equivalent to 30 to 35 percent of Japan's national output; the U.S. figure was about half that. At the same time, the Japanese developed cooperative relationships between labor and management that encouraged high-quality work and rapid productivity growth. Finally, they took existing technologies, in consumer electronics, for example, and produced higher-quality goods at lower costs than their foreign competitors.

Practical Problems

Even if these propositions were true and a U.S. industrial policy could be rationalized, the impediments to implementing a successful policy would be formidable. First, what criteria should be used to decide which industries are worthy of support? One commonly suggested criterion today—one that can be justified on economic grounds—is to subsidize high-tech industries that generate positive spillovers in other parts of the economy. A technical innovation by one firm, for example, made possible by government subsidies, could be incorporated by other firms, producing a boost for the economy that exceeds the cost of the subsidy.

The transition from theory to the real world is a good deal more complicated, however. To work, the benefits and the costs of any policy must be identified and measured correctly. Each subsidy given to an industry or firm generates an opportunity cost: the cost of foregone alternatives. In other words, to correctly evaluate a policy, you need to know not only what you're getting, but also what you're giving up. Based on industrial policy experiments in several countries, most economists have little confidence in the government's ability to measure these benefits and costs properly.

Another criterion for picking winners would be based on comparative advantage. In simple terms, a country has a comparative advantage in producing goods that require a larger share of its abundant (and, hence, least costly) resource. While other factors are important too, this basic proposition indicates that a nation should produce and export goods that are relatively inexpensive (in terms of resource use) and import goods that are relatively expensive to produce domestically. The United States has relatively more technology, capital and high-skill labor than low-skill labor, and therefore, all else equal, should concentrate in producing high-tech, capital-intensive goods that require an educated work force.

This very general proposition does not help determine, however, which industries in which countries will succeed. We know that advanced countries import and export a wide range of goods within the same industry, like automobiles. These goods share similar broad characteristics, but have other special qualities that set them apart. Because industrial specialization is determined by factors other than resource endowments, however, economists are wary of any attempt to target very specific industry sectors for assistance. The knowledge necessary to determine in advance what will be successful simply does not exist. Individual entrepreneurship and initiative, as shown by Henry Ford in the development of the automobile, for example, are key components in the specialization process and cannot be anticipated by government planners. The government can best help this specialization process by Manufacturing Productivity: Making More With Less creating a sound economic environment, one that is free of distortionary fiscal, monetary and regulatory policies.

The criteria offered for choosing which declining industries to support are even weaker. Some suggest that the federal government assist older and troubled industries on the grounds that other governments are heavily subsidizing them in their countries; the steel industry is a good example of this. That would mean, however, supporting industries that have low or negative investment returns and excess capacity. Instead of encouraging the private sector to devote resources to unprofitable industries that other countries are subsidizing, it makes more sense to take advantage of that foreign subsidy by buying the cheaper foreign goods.

The American political system presents a final challenge to successfully implementing any industrial policy. Given the power of interest groups in our political system, it is likely that government support of an industry would be based more on political considerations than economic merits. It's also likely that every industry would demand (and get) a share of the pie, thus diluting the effects of any targeted policy. And there is the further problem of withdrawing support when it is no longer needed or when it is clear the policy has failed. To paraphrase economist Milton Friedman, there is nothing more permanent than a temporary government program.

Increasing investment in high-tech industries and retraining workers in declining industries—two of the major goals of today's industrial policy advocates—are worthy goals. When a government directs resources toward some industries, however, it effectively takes them away from others. Economic theory and practical experience teach us that individual entrepreneurs and firms are better equipped to make these choices. The portion of U.S. workers in manufacturing has steadily declined in the postwar era. Today, about one in five workers is employed in the manufacturing sector compared with one in three at the end of WWII. Despite this decline, manufacturing output as a share of total output has remained fairly constant, around 20 to 23 percent. What this demonstrates is a significant improvement in manufacturing productivity.

References

Richard N. Cooper. "Industrial Policy and Trade Distortion: A Policy Perspective," in A. Michael Spence and Heather A. Hazard, eds., International Competitiveness (1988).

Paul R. Krugman. "Targeted Industrial Policies: Theory and Evidence," in Industrial Change and Public Policy, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (August 1983).

Assar Lindbeck. "Industrial Policy as an Issue in the Economic Environment," The World Economy (December 1981).

Charles L. Schultze. "Industrial Policy: A Dissent," The Brookings Review (Fall 1983).

Laura D'Andrea Tyson. Who's Bashing Whom? Trade Conflict in High-Technology Industries, Institute for International Economics (November 1992).

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us