Pace of GDP Growth, Disinflation Key in U.S. Economic Outlook

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The outlook for U.S. real GDP growth has improved over the past three months on some stronger-than-expected data in January and February.

- Although CPI inflation increased by more than expected in January, inflation continues to slow modestly on a year-to-year basis since peaking at 8.9% in June 2022.

- The Federal Reserve has signaled that its target range for the federal funds rate—currently 4.5% to 4.75%—is likely to surpass 5% this year.

- The demand for labor remains strong. Job growth accelerated sharply in January, and the unemployment rate fell to a nearly 54-year low of 3.4%.

A Recap of 2022

U.S. economic growth, as measured by real gross domestic product (GDP), downshifted markedly in 2022, slowing from a 5.7% increase in 2021 to a 0.9% increase in 2022.Unless noted otherwise, annual growth rates are measured as percent changes from fourth quarter to fourth quarter for quarterly data (e.g., GDP) and from December to December for monthly data (e.g., consumer price index). Although the stepdown in growth was broad-based, growth slowed the most in personal consumption expenditures and residential fixed investment. In fact, the latter declined by 19% in 2022.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the federal funds rate target range by 425 basis points in 2022. These actions slowed activity in interest rate-sensitive sectors like housing, but also had the intended effect of slowing the rate of price inflation—though admittedly, the reversal of some temporary factors (e.g., supply-side disruptions) also mattered: Growth of the all-items (headline) consumer price index (CPI) declined from 7.2% in December 2021 to 6.4% in December 2022, while the growth of the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index slowed from 6% in December 2021 to 5.3% in December 2022.

Tighter monetary policy also affected financial market conditions: Stock prices (as measured by the S&P 500) fell by 19.4% in 2022, and the trade-weighted value of the dollar appreciated by 5.5%. However, the Federal Reserve’s actions had only a modest effect on the labor market, as job growth averaged a little more than 400,000 per month in 2022 and the unemployment rate fell modestly to 3.5%.

The Economic Outlook for 2023

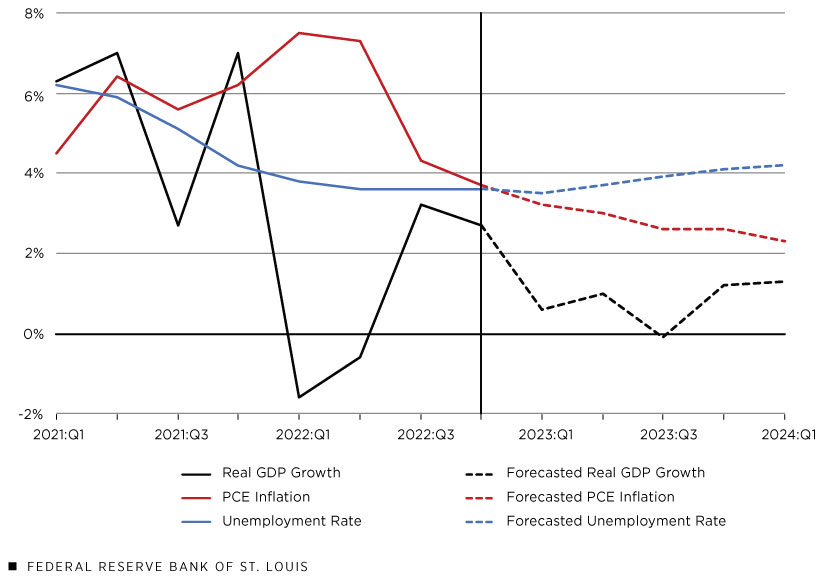

Most of the weakness in the broader economy occurred in the first half of 2022, when real GDP declined at annual rates of 1.6% and 0.6% in the first and second quarters, respectively. Real GDP growth then accelerated over the second half of the year, averaging 3%. Thus, the economy entered 2023 with a healthy amount of forward momentum in spending and income. This momentum, as seen in the figure below, is not expected to carry forward in 2023, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

Consensus Forecasts for Real GDP Growth, PCE Inflation and Unemployment in 2023

SOURCE: Survey of Professional Forecasters, February 2023.

NOTES: The figure shows quarterly percent changes at annual rates except for the unemployment rate, which is the average for the months of the quarter indicated. Data for the first quarter of 2023 to the first quarter of 2024 are forecasted.

The narrative surrounding the U.S. macroeconomic consensus forecast for 2023 can be summarized in a few key points:

- Disinflation: Forecasters predict that PCE inflation will steadily decline to under 3% in the second half of 2023, but it is expected to remain above the FOMC’s 2% target and sit at 2.3% in the first quarter of 2024.

- Below-trend output growth: Forecasters expect real GDP growth to average less than 1% in 2023, with growth slipping below zero (-0.1%) in the third quarter. According to the SPF, the U.S. economy’s projected long-term real GDP growth is 2%.

- Modestly higher unemployment: The civilian unemployment rate is projected to drift higher in 2023 and into early 2024, from 3.6% in the fourth quarter of 2022 to 4.2% in the first quarter of 2024.

The outlook for the real economy (income, expenditures and employment) in 2023 has improved since the SPF was published and comes in response to some better-than-expected data measuring economic activity in January and February. Here are some of the key data and their implications for the near-term outlook:

- The January employment report showed that labor market conditions remained exceptional at the beginning of the year. Nonfarm payroll employment rose by 517,000—more than double expectations—and aggregate hours worked jumped by 1.2%. The unemployment rate fell one-tenth of a percentage point to 3.4%, its lowest level since May 1969. Initial weekly claims for state unemployment insurance benefits remained near historic lows in the first two weeks of February.

- Retail sales were also much stronger than expected in January, rising 3% (versus an expected 1.6%). Sales of domestically produced passenger cars and light trucks were also exceptionally strong, rising 18.8% in January.

- Manufacturing production rose 1% in January after falling 1.8% in December 2022 and 0.8% in November 2022. Motor vehicle assemblies also rose in January (1.2%) after falling by 10.2% over the last two months of 2022. S&P Global’s manufacturing and services purchasing managers’ indexes were stronger than expected in February.

- Housing remains the soft spot in the economy. In January, total private housing starts fell 4.5% to 1.31 million units at an annual rate, and existing home sales fell to their lowest level since October 2010. However, sentiment among homebuilders is improving, as the National Association of Home Builders Housing Market Index rose for the second straight month in February, posting its highest level since September 2022.

On balance, key January and February data on employment, expenditures and output suggest that the economy is beginning the year with a healthy pace of growth. In response, some forecasters have raised their estimate for first quarter real GDP growth and lowered their estimate of the probability of a recession in 2023.

Caveats and Risks to the Economic Outlook

The old adage about one month of economic data not making a trend applies in nearly all circumstances when it comes to forecasting and tracking the U.S. economy. Weekly chain store sales data suggest that retail sales could be much weaker in February. Moreover, the pace of job growth in February will probably fall far short of January’s outsized gain. Regardless, the economy appeared to carry its momentum forward into early 2023—and that is a positive development. If the real side of the economy was the end of the story, the outlook would be pretty good. Alas, that is not case.

Higher-than-desired inflation remains a key downside risk. The path to durable disinflation was more evident in the fourth quarter of 2022, when both the CPI and the PCE price index increased at annual rates (4.2% and 3.7%, respectively) that were less than half those registered over the first half of 2022. But the low headline inflation numbers seen in November 2022 and December 2022 reversed in January, as both the headline and core CPI and PCE price index rose sharply—the headline PCE price index by 0.6% and the core by 0.6% as well. Similarly, the producer price index for January also showed higher-than-expected gains in its headline and core numbers.

Through mid-February, crude oil and gasoline prices were modestly higher than their January averages, so the headline CPI could post another sizable gain in February. Indeed, the possibility of rising energy and commodity prices poses a risk to the near-term inflation outlook. In a February report, the International Energy Agency forecasted that China’s post-COVID-19 “reopening” will help spur a record level of oil demand this year. On the supply side, sanctions against Russia and the country’s subsequent announcement that it intends to reduce production this year enhances uncertainty.

FOMC members have repeatedly communicated to the public and financial market participants that continued high inflation is a clear and present danger to the U.S. economy. Certainly, strong data in January assuage some of the recession fears that gripped financial markets at the end of 2022 and into early 2023. But easing recession fears can be a two-edged sword for policymakers, because the combination of stronger-than-expected income, expenditures and inflation data raises the probability that disinflation may be a longer and bumpier path than expected. Markets are also aware of this scenario, which is probably why market-based expectations for inflation over the next five years rebounded in February, and why financial market participants no longer expect the FOMC to begin reducing the federal funds rate target range in 2023, as was priced into the markets earlier this year.

Recession Probabilities Decline, but Uncertainty Remains High

Key data in January suggest that the economy began 2023 on solid footing, although there are some inklings that the pace of retail sales could be slower in February. Continued high inflation rates and a rebound in market-based measures of inflation expectations indicate that downside risks to the economy remain elevated. For these reasons, uncertainty about both the pace of economic growth and the degree of disinflation over the near term—as reflected in the consensus forecasts—remains extraordinarily high.

Notes

- Unless noted otherwise, annual growth rates are measured as percent changes from fourth quarter to fourth quarter for quarterly data (e.g., GDP) and from December to December for monthly data (e.g., consumer price index).

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us