Is the Era of Overdraft Fees Over?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Overdraft fees are a significant source of revenue for U.S. banks. However, banks’ overdraft and nonsufficient funds fee revenue has fallen sharply since peaking in 2019.

- Banks, particularly large banks, are beginning to cut back on overdraft fees and offer lower-cost alternatives like small-dollar loans in response to competitive and regulatory pressure.

- The speed at which banks continue modifying overdraft services will depend largely on whether they are able to compensate elsewhere for lower overdraft fee revenue.

Banks launched overdraft services for account holders in the 1990s, selling them as a convenience for customers. In exchange for a fee, banks would cover customers’ overdrawn checks—those written for an amount greater than the balance in the account—instead of allowing them to bounce. Similarly, for a fee, banks would honor debit card transactions or electronic payments made without sufficient funds in the account rather than declining them. Collecting overdraft fees has proved very profitable for banks. In recent years, several of the nation’s largest banks have reported more than $1 billion annually in overdraft fee income, while some smaller banks have recorded overdraft fee income exceeding 20% of earnings.See the Nov. 7, 2022, Brookings report Getting Over Overdraft.

A relatively small proportion of bank customers account for the lion’s share of overdraft fees. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), people who frequently overdraft their accounts represented just 9% of bank customers but generated almost 80% of overdraft and nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees in 2017.See the August 2017 CFPB report Data Point: Frequent Overdrafters (PDF). A bank may charge overdraft fees if the customer does not have enough funds in the account for a transaction and the bank covers it on the customer’s behalf. A bank may charge NSF fees if the customer’s account is overdrawn and the bank declines the transaction. Consulting firm Oliver Wyman estimates that customers who heavily use overdraft services generate, on average, more than $700 in profit for the bank per year on a basic bank account; customers who don’t use overdraft services produce an average of $57 in profit for the bank per year.See the 2020 Oliver Wyman report Beyond Overdraft: A Path to Replacing Unsustainable Revenue (PDF).

Despite the fees, overdraft protection remains popular. According to research by Curinos, a global data intelligence firm, more than 60% of overdrafts come from consumers who intend to use the service. Two-thirds of the consumers that Curinos surveyed indicated they did not want to see access to the service reduced, despite the expense.See the Dec. 1, 2021, Curinos report Competition Drives Overdraft Disruption.

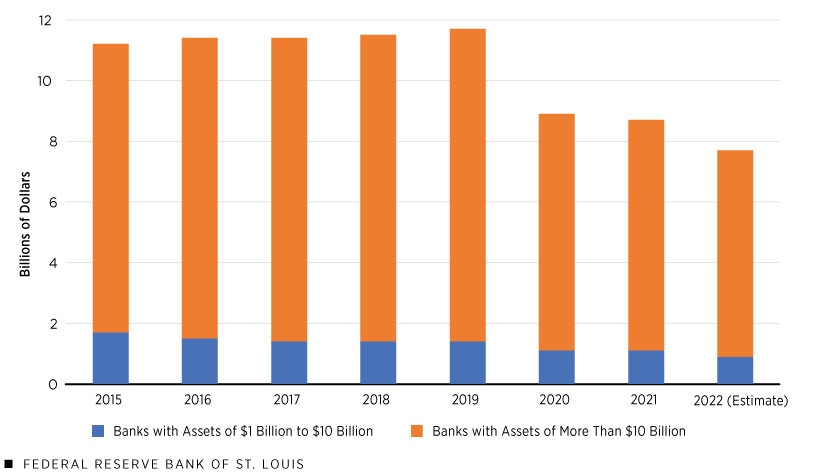

As the figure below illustrates, overdraft and NSF fee revenue at U.S. banks has fallen sharply since peaking at $11.7 billion in 2019.This number excludes overdraft and NSF fee revenue at banks with assets of less than $1 billion because they are not required to report that information. A CFPB estimate that included smaller banks and credit unions put the industry’s 2019 overdraft and NSF fee revenue at $15.5 billion. For a more detailed description of the CFPB’s methodology, see their December 2021 report Data Point: Overdraft/NSF Fee Reliance Since 2015–Evidence from Bank Call Reports (PDF). Several developments explain this decline. Decreased consumer spending and an influx of government stimulus funds during the pandemic increased bank customers’ deposit balances, lessening the demand for overdraft. At the same time, consumer backlash, scrutiny from Congress and regulators, and increased competition from nonbank providers have prompted banks—especially large ones—to change or eliminate their overdraft programs. A growing number of banks are offering lower-cost alternatives to overdraft services that can cover the account deficit and help customers fulfill other goals, such as building credit.

Overdraft and NSF Fee Revenue at U.S. Commercial Banks, 2015-2022

SOURCE: Reports of Condition and Income for U.S. commercial banks.

NOTE: The data exclude banks with assets of less than $1 billion because those banks are not required to report overdraft and NSF fee revenue.

Bank Overdraft Fees under Pressure

Backlash against overdraft fees has waxed and waned over time. Stories of $5 cups of coffee turning into overdraft charges of $35 or more still appear regularly in media reports.See, for example, the June 22, 2021, New York Times article “Banks Slowly Offer Alternatives to Overdraft Fees, a Bane of Struggling Spenders.” New regulations have quelled some of the negative sentiment, however. For example, banks are no longer permitted to automatically enroll customers in overdraft protection programs; customers must opt in.This requirement came from a 2010 change to Regulation E, which governs electronic fund transfers. The prohibition applies to one-time debit card transactions and ATM withdrawals. Overdraft fees can be charged, however, when a check or a recurring electronic payment would overdraw an account. Banks may still charge NSF fees when presented a check or automated clearinghouse transaction for an account with insufficient funds to cover the payment. See this article from the CFPB on rules around overdraft fees for more information.

Regulators—including the CFPB, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and several state banking agencies—have pressed banks to cut back on overdraft fees and improve disclosures. In recent years, overdrafts have been the subject of congressional hearings and proposed legislation that would mandate certain disclosures and alter some overhead-related bank practices, such as placing a limit on the number of overdrafts permitted in a given time period.In 2022, for example, the U.S. House Financial Services Committee passed the Overdraft Protection Act and the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee held a subcommittee hearing entitled “Examining Overdraft Fees and Their Effects on Working Families.”

Competition—from other banks and nonbank providers such as fintech firms—arguably has affected overdraft practices more than anything else. The growth of online and mobile banking has given customers more choices, and those wishing to avoid overdraft fees are voting with their feet by switching to competitors. In addition to introducing low or no overdraft charges, some fintech firms have created financial management tools for account holders. The digital banking platform Dave, for example, created a bank account in partnership with Evolve Bank & Trust that has no minimum balance or overdraft fees, real-time spend alerts and early access to paycheck deposits.

Overdraft Program Changes

Banks have modified their overdraft programs in response to these factors, with large banks taking the lead. These changes include:

- Lowering the overdraft fee (from $35 to $10, for example)

- Increasing the trigger value (charging a fee only when the overdraft exceeds a given amount)

- Curing (adding a grace period to allow customers to cover the shortfall)

- Reducing the daily maximum number of overdraft fees charged (the average is four to eight)

- No longer charging fees to cover transactions that overdraw linked accounts

- Giving customers early access to their direct deposits

Some banks are giving customers notice of low balances and offering them a choice to stop or delay automatic payments that would trigger an overdraft; customers must then decide between paying an overdraft fee to the bank or a late payment fee to a creditor, such as a credit card company.

The research arm of Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that these changes will save customers of large and regional banks more than $4 billion a year in overdraft fees; the CFPB projects half those savings will come from three institutions: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo.See the June 21, 2022, Pew article “Large Banks Improve Overdraft Policies and Cut Fees” and the Dec. 1, 2021, CFPB press release “CFPB Research Shows Banks’ Deep Dependence on Overdraft Fees.” Citigroup, the nation’s third-largest bank, has eliminated overdraft fees altogether. By August 2022, 13 of the country’s 20 largest banks had stopped charging NSF fees as part of their overdraft programs, and four more were scheduled to do so by the end of 2022.See the Dec. 19, 2022, American Banker article “How 2022 Hastened the Decline of Overdraft Fees.” This represents a dramatic change from a year earlier, when 18 of the 20 largest U.S. banks charged NSF fees.

Small-Dollar Loans: An Overdraft Alternative

Several banks have taken a further step, turning account deficits into small-dollar loans that will cost the customer less than a series of overdrafts. A negative balance can be turned into an installment loan with a fixed rate or a charge based on the amount borrowed, rather than on the number of transactions that overdrew the account. Customers then make regular payments on these loans, allowing them both to avoid overdrafts and build credit.

The move toward small-dollar loans as alternatives to overdrafts received a boost in 2020 when federal banking regulators issued guidance encouraging financial institutions to offer such loans to both consumers and small businesses.Specifically, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the FDIC, the National Credit Union Administration and the OCC issued the guidelines. See the May 2020 press release “Interagency Lending Principles for Offering Responsible Small-Dollar Loans” (PDF). As of January 2023, six of the eight largest U.S. banks, ranked by number of branches, offered small-dollar loans.See the Jan. 24, 2023, Pew article “Six of the Eight Largest Banks Now Offer Affordable Small Loans.” In addition to substituting for overdrafts, small-dollar loans are being touted by consumer groups as less costly alternatives to payday loans, auto-title loans and rent-to-own agreements. Pew estimates that small-dollar loans at four of these large banks—Bank of America, Huntington Bank, U.S. Bank and Wells Fargo—are priced at least 15 times lower than the average payday loan.

Looking Ahead

Banks have responded to consumer, competitive and regulatory pressures to overhaul their overdraft programs, and that trend is expected to continue. Most of the action to date has occurred at very large institutions; the vast majority of the nation’s banks (and credit unions) have yet to make changes. Financial institutions, like other firms, must operate in the black. As a result, the speed at which they make changes will depend largely on the relative importance of overdraft and NSF fee income to their bottom lines and on whether banks can compensate elsewhere for lower overdraft fee revenue.

Notes

- See the Nov. 7, 2022, Brookings report Getting Over Overdraft.

- See the August 2017 CFPB report Data Point: Frequent Overdrafters (PDF). A bank may charge overdraft fees if the customer does not have enough funds in the account for a transaction and the bank covers it on the customer’s behalf. A bank may charge NSF fees if the customer’s account is overdrawn and the bank declines the transaction.

- See the 2020 Oliver Wyman report Beyond Overdraft: A Path to Replacing Unsustainable Revenue (PDF).

- See the Dec. 1, 2021, Curinos report Competition Drives Overdraft Disruption.

- This number excludes overdraft and NSF fee revenue at banks with assets of less than $1 billion because they are not required to report that information. A CFPB estimate that included smaller banks and credit unions put the industry’s 2019 overdraft and NSF fee revenue at $15.5 billion. For a more detailed description of the CFPB’s methodology, see their December 2021 report Data Point: Overdraft/NSF Fee Reliance Since 2015–Evidence from Bank Call Reports (PDF).

- See, for example, the June 22, 2021, New York Times article “Banks Slowly Offer Alternatives to Overdraft Fees, a Bane of Struggling Spenders.”

- This requirement came from a 2010 change to Regulation E, which governs electronic fund transfers. The prohibition applies to one-time debit card transactions and ATM withdrawals. Overdraft fees can be charged, however, when a check or a recurring electronic payment would overdraw an account. Banks may still charge NSF fees when presented a check or automated clearinghouse transaction for an account with insufficient funds to cover the payment. See this article from the CFPB on rules around overdraft fees for more information.

- In 2022, for example, the U.S. House Financial Services Committee passed the Overdraft Protection Act and the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee held a subcommittee hearing entitled “Examining Overdraft Fees and Their Effects on Working Families.”

- See the June 21, 2022, Pew article “Large Banks Improve Overdraft Policies and Cut Fees” and the Dec. 1, 2021, CFPB press release “CFPB Research Shows Banks’ Deep Dependence on Overdraft Fees.”

- See the Dec. 19, 2022, American Banker article “How 2022 Hastened the Decline of Overdraft Fees.”

- Specifically, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the FDIC, the National Credit Union Administration and the OCC issued the guidelines. See the May 2020 press release “Interagency Lending Principles for Offering Responsible Small-Dollar Loans” (PDF).

- See the Jan. 24, 2023, Pew article “Six of the Eight Largest Banks Now Offer Affordable Small Loans.”

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us