Is Monetary Policy Sufficiently Restrictive?

Since mid-2021, inflation has been running well above the 2% target set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).The FOMC’s 2% target is based on the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. In an effort to put downward pressure on inflation, in March 2022 the FOMC began a series of increases to the federal funds rate (i.e., the policy rate), with the aim of making monetary policy “sufficiently restrictive” to return inflation to 2% over time, as noted in several of the committee’s post-meeting statements since November.

The current range for the federal funds rate stands at 5%-5.25% following the increase at the May FOMC meeting. How can we know if the policy rate is at a level that could be considered sufficiently restrictive? In a recent presentation, I used monetary policy rules to examine this question.See my presentation at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on May 12, 2023, “The Monetary-Fiscal Policy Mix and Central Bank Strategy.” For an earlier analysis, see my presentation in Louisville, Ky., on Nov. 17, 2022, “Getting into the Zone.”

Monetary Policy Rules as a Guidepost

Monetary policy rules provide explicit recommendations for the level of the policy rate given macroeconomic conditions, which then serve as a guidepost for where policy should be. One of the most famous monetary policy rules is the “Taylor rule,” which was developed by John Taylor of Stanford University and has been widely accepted in monetary policy discussions over the last 30 years.See John Taylor’s December 1993 Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy paper, “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice” (PDF). Versions of his rule (“Taylor-type rules”) have been tested in commonly used macroeconomic models and have been argued to characterize close-to-optimal monetary policy.

A Taylor-type rule requires:

- A value for the short-term real rate of interest that would prevail if economic output was at potential and the inflation rate was at target

- A measure of the size of the current inflation gap (i.e., deviation of inflation from target)

- A measure of how strongly the policymaker should react to the inflation gap

- A value for the size of the output gap (i.e., deviation of output from potential output)

In my presentation, I ignored the output gap for recent periods. The FOMC has stated that “policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level.”See the FOMC’s “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” (PDF), adopted effective Jan. 24, 2012, and reaffirmed effective Jan. 31, 2023. Since unemployment is not currently above its longer-run natural rate, it isn’t necessary to factor in an output gap term.

An Assessment of a Sufficiently Restrictive Zone

My approach was to look at a Taylor-type monetary policy rule with generous assumptions, the goal being to provide a minimum recommended level of the policy rate given current macroeconomic conditions. The generous assumptions are ones that tend to recommend a lower policy rate. I also looked at a Taylor-type rule with less generous assumptions, the goal being to offer an upper bound for the recommended policy rate. The area between the lower and upper bounds can be considered the “sufficiently restrictive zone.”

The table below shows the assumptions I used for these two versions of the Taylor-type rule. More details can be found in my May 12 presentation.

| Generous Assumptions | Less Generous Assumptions | |

|---|---|---|

| Measure of inflation used to calculate the inflation gap | Dallas Fed trimmed-mean PCE inflation | Core PCE inflation |

| Value of the real interest rate | -0.5% | 0.5% |

| Value of the parameter describing the policymaker’s reaction to the inflation gap | 1.25 | 1.5 |

| NOTES: PCE inflation refers to inflation based on the personal consumption expenditures price index. Core PCE inflation excludes food and energy prices. The Dallas Fed trimmed-mean PCE inflation rate is an alternative measure of underlying inflation. | ||

So, can the current policy rate be considered sufficiently restrictive?

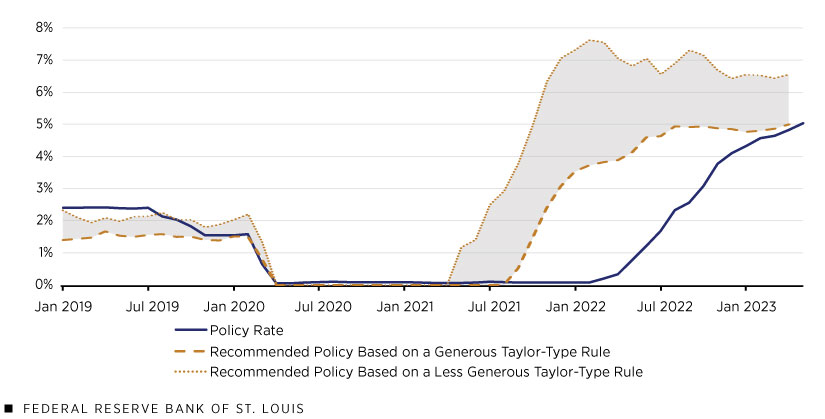

The figure* below shows a zone of realistic values for a sufficiently restrictive level of the policy rate from 2019 through the present. The zone’s lower bound is represented by the Taylor-type rule with generous assumptions, while its upper bound is represented by the Taylor-type rule with less generous assumptions. As seen in the figure, the zone can move in reaction to incoming data; for instance, it started to move up in 2021 as inflation began exceeding 2%.

According to this analysis, monetary policy was about right shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, as the actual policy rate was within the zone. During the pandemic, the policy rate recommended by the Taylor-type rules went to zero along with the actual policy rate. However, the policy rate was below the zone in 2022, suggesting that monetary policy was behind the curve at that point. But since the FOMC has raised the policy rate aggressively during 2022 and into 2023, monetary policy is now at the low end of what is arguably sufficiently restrictive given current macroeconomic conditions.

Actual Policy Rate and Policy Rate Recommendations from Taylor-Type Rules

SOURCES: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections and author’s calculations.

NOTES: The gray-shaded area represents the sufficiently restrictive zone for monetary policy; the values for the lower and upper bounds are through April 2023. Data for the actual policy rate are through May 2023, with the May value being the average of daily values up to May 25.

Monetary Policy in Better Position Today

Monetary policy is in much better shape today with the policy rate at a more appropriate level than it was a year ago, according to this analysis. But where within the sufficiently restrictive zone should the policy rate be? And are there other factors to consider (e.g., financial stability)? Such assessments could be reflected in judgments by the FOMC going forward.

While both headline and core PCE inflation have declined from their peaks in 2022, they remain too high. An encouraging sign that inflation will decline to 2% comes from market-based inflation expectations, which had moved higher in the last two years but have now returned to levels consistent with the 2% inflation target. The prospects for continued disinflation are good but not guaranteed, and continued vigilance is required.

*Editor’s Note: The figure in this article was updated on June 16, 2023, to correct data for the first six months of 2019.

Notes

- The FOMC’s 2% target is based on the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index.

- See my presentation at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on May 12, 2023, “The Monetary-Fiscal Policy Mix and Central Bank Strategy.” For an earlier analysis, see my presentation in Louisville, Ky., on Nov. 17, 2022, “Getting into the Zone.”

- See John Taylor’s December 1993 Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy paper, “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice” (PDF).

- See the FOMC’s “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” (PDF), adopted effective Jan. 24, 2012, and reaffirmed effective Jan. 31, 2023.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us