World Population: What Helps Explain the Explosion?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Past discussion about world overpopulation centered on birth rates, but data for India and the U.S. show death rates also have a significant effect on population dynamics.

- A steep decline in India’s death rate starting in 1950 allowed population growth to remain steady despite a falling birth rate, substantially impacting global population.

- Death rates fell relatively more for an older segment of the population in the U.S. than in India, leading to a median age of 27 in India in 2019 versus 37 in the U.S.

The world population reached 1 billion in 1803. It took 125 years, until 1928, for the world population to hit 2 billion. A mere 32 years later, in 1960, the world population reached 3 billion. Current world population is now approaching 8 billion. These population statistics are from Our World in Data.

A 1968 book titled The Population Bomb famously sounded the alarm on global overpopulation. The book contended that overpopulation leads to “hellish” conditions. See Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, Ballantine Books, New York, 1968. In 1972, a Club of Rome report called The Limits to Growth predicted societal collapse as a consequence of overpopulation.See Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jorgen Randers and William W. Behrens III’s The Limits to Growth, Potomac Associates, Washington, D.C., 1972. Garrett Hardin, known for his article “The Tragedy of the Commons,” described population growth as disastrous.See Garrett Hardin’s December 1968 article, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” in the journal Science. In May 2008, then-President George W. Bush described the 2007-08 rise in world food prices as resulting from the size of India’s population.See the White House’s May 2008 press release “President Bush Discusses Economy, Trade.”

The Population Bomb asserted that the U.S. must help low-income countries lower their high birth rates to solve the overpopulation problem. This was echoed by the World Bank’s 1984 World Development Report. It argued that low-income countries must decrease population growth, which “means to reduce the number of children in an average family.”See the World Bank’s 1984 World Development Report. During this period, the International Planned Parenthood Federation, the Population Council, the United Nations Population Fund and other organizations promoted and funded programs to reduce fertility in low-income countries.See Charles C. Mann's January 2018 article, “The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation,” in Smithsonian Magazine.

Population Growth Is Determined by Birth and Death Rates

This overpopulation discussion focused mostly on births. In this article, we investigate the role of deaths in population dynamics using data for India and the U.S. To understand the focus on birth rates in the discussion of population, it helps to know how births and deaths affect population over time.

Population growth rate—the annual rate at which population increases—offers a useful way to think about this relationship. It equals the birth rate (the number of births divided by the number of people) minus the death rate (the number of deaths divided by the number of people). This can be written as the following:

Population Growth Rate=Birth Rate – Death Rate

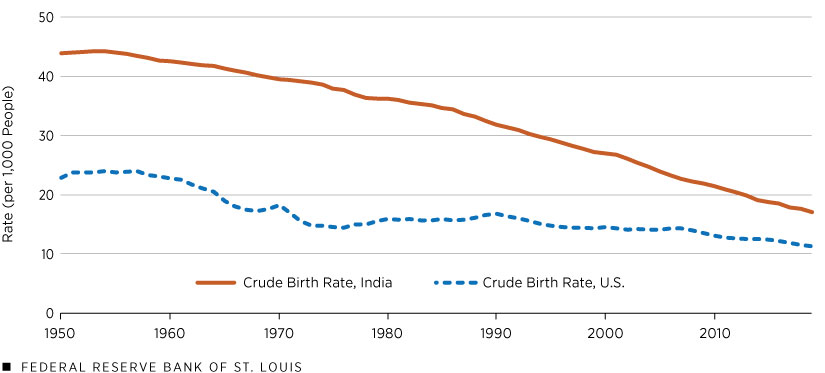

It is easy to see from the equation that, just as the 1984 World Development Report suggested, the population would grow less if the birth rate declined. As the following figure illustrates, the birth rate in India decreased from 44 per thousand people in 1950 to 32 per thousand people in 1990. (The birth rate in India declined further to 17 per thousand people by 2019, almost converging with the birth rate in the U.S., which was about 11 per thousand people.)

Crude Birth Rates in the U.S. and India, 1950-2019

SOURCE: United Nations, World Population Prospects 2022.

NOTE: Crude birth rate is the number of live births per 1,000 people.

Despite the decline in birth rate, however, the population growth rate stayed the same, around 2.25%, from 1950 to 1990. So, why the discrepancy?

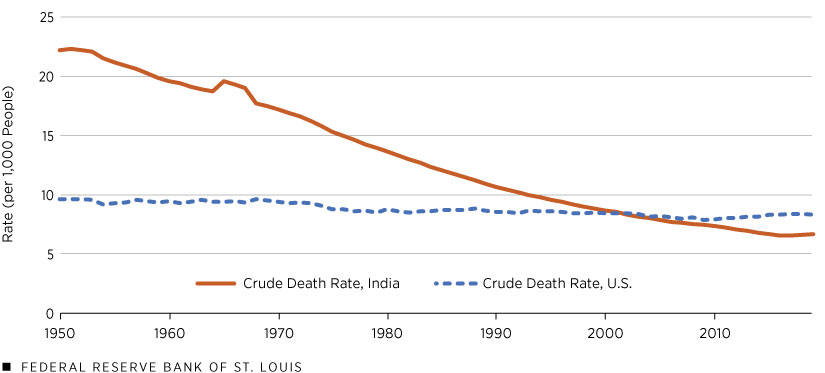

India’s population growth rate stayed the same despite the falling birth rate because of the dynamics of its death rate. The following figure illustrates the steep decline in death rates in India, from 22 deaths per thousand people in 1950 to 10.7 deaths per thousand people in 1990. India’s death rate fell further to 6.7 per thousand people in 2019. Over this period, death rates in the U.S. decreased by only 1.3 deaths per thousand people—from 9.6 to 8.3. In 2019, the death rate in India was lower than that in the U.S. While the earlier overpopulation discussion emphasized the role of birth rates, it failed to account for how the decline in death rates affects population growth.

Crude Death Rates in the U.S. and India, 1950-2019

SOURCE: United Nations, World Population Prospects 2022.

NOTE: Crude death rate is the number of deaths per 1,000 people.

The Decline in India’s Death Rate Substantially Impacted Current Global Population Levels

To assess the quantitative impact of the decline in death rates, we ran a counterfactual exercise and calculated what India’s population would have been if we held India’s death rate fixed at the 1950 level. That is, we calculated India’s population each year starting in 1950 using the year’s actual birth rate and the 1950 death rate instead of the year’s particular death rate.

The actual population in India increased from 360 million in 1950 to nearly 1.4 billion in 2019; whereas, in the counterfactual example, India’s population increased from 360 million to only 760 million in 2019. That’s a difference of about 640 million fewer people.

World population increased by 5.34 billion people from 1950 to 2019. India accounted for 20% of this increase. If India’s death rate over this period had remained the same as in 1950, the world population would have increased by only 4.7 billion, with just 8.5% attributable to India. That is, the world population also would have been smaller by 640 million people.

Death Rate Affects Age Composition

A decline in the death rate has implications for the age composition of the population, depending upon whether the decline occurred among younger or older age groups. For instance, if the decline in death rate is predominantly in the 0-4 age group, then the population will get relatively younger; if the decline is predominantly in the 70-74 age group, then the population will get relatively older.

In India, there were roughly 81 deaths per thousand people in 1950 in the 0-4 age group; this number declined more than 90% to fewer than seven deaths per thousand people in this age group in 2019. In contrast, the death rate in the 70-74 age group declined by less than 45%, from 79 per thousand people to 44 per thousand people. The median age in India in 2019 was 27; in absolute terms, the number of people 27 and younger in India was more than twice the entire population of the U.S.

In the U.S., the decline in the death rate in the 0-4 age group was about 84% during this period, but the decline in the 70-74 age group was about 58%. The relative decrease in death rates in the older age group was larger in the U.S. than in India. Consequently, the median age in the U.S. in 2019 was 37; two-thirds of India’s population in 2019 was below this age.

Notes

- These population statistics are from Our World in Data.

- See Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, Ballantine Books, New York, 1968.

- See Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jorgen Randers and William W. Behrens III’s The Limits to Growth, Potomac Associates, Washington, D.C., 1972.

- See Garrett Hardin’s December 1968 article, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” in the journal Science.

- See the White House’s May 2008 press release “President Bush Discusses Economy, Trade.”

- See the World Bank’s 1984 World Development Report.

- See Charles C. Mann's January 2018 article, “The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation,” in Smithsonian Magazine.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us