Making Sense of Inflation Measures

In 2022, inflation reached its highest level in 40 years. For most Americans, this is their first experience with high inflation. Indeed, many may wonder how exactly inflation is measured, particularly as the media cites different inflation measures like “headline CPI” or “core PCE.” This is not a trivial question. In fact, measuring inflation is one of the most difficult issues studied by economists.

An Old Favorite: CPI

Inflation is the percentage change in overall prices in the economy over a specified period, typically a year; it’s not an increase in the prices of a few products. Given the difficulties in following every price in the country, economists create a price index to approximate the overall price level.

The most widely cited measure of inflation is the headline consumer price index (CPI), which is calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The original version of this index was created in 1919, as policymakers sought a better way to measure rising consumer prices in the aftermath of World War I.

The CPI, which rose 8.5% in July 2022 from a year earlier, measures the price changes for a basket of goods and services purchased by the typical urban consumer. The items in this basket are weighted by their relative importance in consumer expenditures. For example, housing—rent and other spending on shelter—accounts for 33% of the index, while medical care accounts for nearly 9%.

Of course, any price index like the CPI has to take into account changing consumption patterns. New items come in and old items leave. Currently, the CPI weights are adjusted every two years using two years of consumer spending data; beginning next year, however, the BLS will update weights annually using one year of data.

Targeting PCE Inflation

Before 2000, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) typically watched the CPI to gauge inflation. But in the 1990s, the Federal Reserve took a careful look at alternative inflation measures and decided that it preferred a different measure: the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. Though the two indexes are closely related, there are reasons why the PCE is considered a better tool for policymakers.

The PCE price index, which rose 6.3% in July 2022 from a year earlier, is derived from a broader index of prices than the CPI’s more narrow set of goods and services. The argument that carried the day was that a more comprehensive index of prices provides a better way to gauge underlying inflationary pressures. Because the PCE includes more goods and services, the index’s weights for particular items will differ from those in the CPI. For example, housing has a weight of about 16% in the PCE price index versus 33% in the CPI.

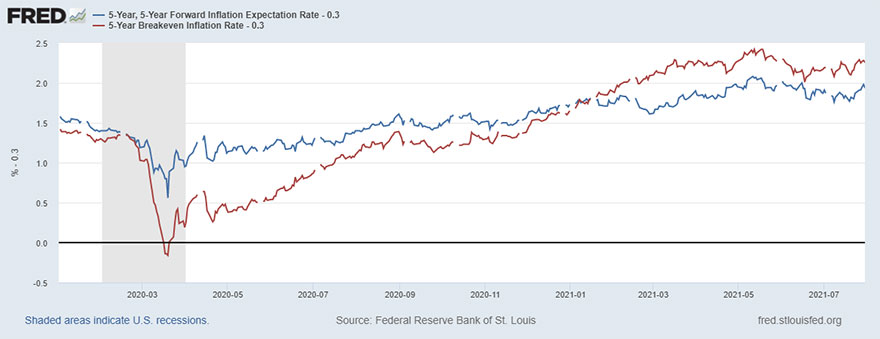

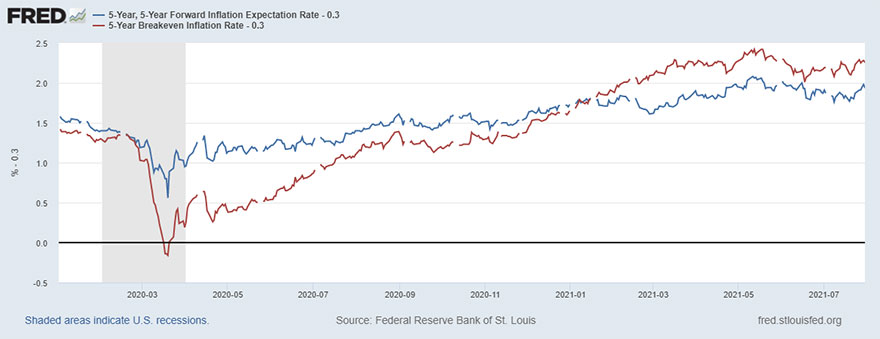

Headline PCE Inflation versus Headline CPI Inflation

Another advantage in tracking the PCE is that the index’s weights are updated monthly, versus biennially for the current CPI. Thus, the PCE can quickly reflect the impact of new technology or an abrupt change in consumer spending patterns. For example, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly shifted consumption from services like restaurants to goods like electronics.Assistant Vice President Michael McCracken and co-author Aaron Amburgey examined the problem of shifting consumption patterns and measuring inflation in their February 2021 On the Economy blog post, “How COVID-19 May Be Affecting Inflation.” The economists at the St. Louis Fed extensively research inflation.

For these reasons, the FOMC’s target in terms of inflation is the headline PCE inflation rate. And the target the FOMC has set is 2%, a level that policymakers judge to be consistent with achieving price stability and maximum employment. On average, inflation was slightly below this target before the pandemic’s economic shock; from 1995 through 2019, the average headline PCE inflation rate was 1.8%. In 2020, the FOMC adopted a new policy framework designed to better ensure that inflation would average 2% over time.

Other Inflation Measures

While the FOMC targets headline PCE inflation, policymakers also watch other measures to gauge inflationary pressures. The headline PCE measure can be quite volatile due to the effects of extreme price movements for certain products. To get a sense of where underlying inflation really is, economists often look at some summary measure of inflation that doesn’t include these volatile prices.

A so-called “core” index—whether it be PCE or CPI—excludes food and energy components. That has some simplicity around it, but it’s not satisfactory.For a detailed explanation of the deficiencies in using a core index, see my 2011 Review article, “Measuring Inflation: The Core Is Rotten.” (PDF) There are better ways to analyze underlying inflation than to throw out certain goods and services, especially those that hit low- to moderate-income consumers the hardest when prices rise. And even if you exclude food and energy prices, the remaining part of the index is still affected by their volatility; restaurant prices would be a classic example.

More recently, other statistical ideas have been developed. One method looks at price change distribution for the entire range of goods and services.For an example of how studying price change distribution can be useful in determining the pervasiveness of inflationary pressures, see St. Louis Fed Assistant Vice President Fernando Martin’s October 2021 On the Economy blog post, “How Widespread Are Price Increases in the U.S.?”

One commonly used measure of this type is the Dallas Fed trimmed-mean PCE inflation rate, which removes the upper tail (the largest price changes) and the lower tail (the smallest price changes) and then takes a weighted average of the price changes for the remaining components. This measure has been popular as a tool for examining trends and overall inflation as opposed to special factors that might be driving inflation. Of course, these types of measuresOther measures include the Cleveland Fed’s median and trimmed-mean CPI and the Atlanta Fed’s sticky-price CPI. tend to be more persistent and move more slowly than headline inflation measures.

Other Inflation Measures: Core PCE, Core CPI and Dallas Fed Trimmed Mean

While each of these measures provides different and important insights into inflation, the FOMC target is nonetheless headline PCE inflation of 2%. And bringing today’s inflation rate back down to that 2% target is the top priority for the FOMC.

Notes

- Assistant Vice President Michael McCracken and co-author Aaron Amburgey examined the problem of shifting consumption patterns and measuring inflation in their February 2021 On the Economy blog post, “How COVID-19 May Be Affecting Inflation.” The economists at the St. Louis Fed extensively research inflation.

- For a detailed explanation of the deficiencies in using a core index, see my 2011 Review article, “Measuring Inflation: The Core Is Rotten.” (PDF)

- For an example of how studying price change distribution can be useful in determining the pervasiveness of inflationary pressures, see St. Louis Fed Assistant Vice President Fernando Martin’s October 2021 On the Economy blog post, “How Widespread Are Price Increases in the U.S.?”

- Other measures include the Cleveland Fed’s median and trimmed-mean CPI and the Atlanta Fed’s sticky-price CPI.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us