Weaker GDP Growth, Inflation Uncertainty Dim U.S. Economic Outlook

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The outlook for U.S. real GDP growth has dimmed appreciably over the past year, with the consensus prediction now calling for it to increase by 0.8% in 2023.

- Headline CPI inflation is forecast to slow, from a projected 7.7% in 2022 to 3.4% in 2023. The Fed has signaled further interest rate hikes are likely.

- The pace of job gains is expected to slow in 2023, but the strength of the current labor market stands in stark contrast to weakness in other areas of the U.S. economy.

The pace of economic activity has been uneven this year. After declining at annual rates of 1.6% and 0.6% in the first quarter and second quarter of 2022, respectively, U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at a stronger-than-expected 2.6% annual rate in the third quarter. Growth in the third quarter was unusually brisk because of a large contribution from real net exports—the largest in 42 years, in fact. However, the boost from net exports is likely to reverse over the near term because the Federal Reserve Board’s real broad dollar index, a trade-weighted measure of the dollar against a basket of currencies, was at a 37-year high in October, and global economic growth, particularly in Europe and China, is weakening.

Accordingly, the November Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) projected that real GDP will increase at a 1% annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2022. If this growth is realized, real GDP would increase by 0.8% over the four quarters ending in the fourth quarter of 2022, far below last year’s 5.7% growth rate and well under the economy’s trend growth rate of about 2%. The SPF projects that GDP growth will remain positive in 2023, but uncertainty remains above average. See figure 4.D. from the FOMC’s September 2022 Summary of Economic Projections (PDF). The Federal Reserve’s commitment to restore price stability, while necessary, could cause the economy to slow further next year. Indeed, a recession is not out of the question.

Key Themes in the Near-Term Outlook

The battle against high inflation remains front and center for Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) policymakers. Through the first 10 months of 2022, the all-items consumer price index (CPI) increased at an annual rate of 7.7%, while the core CPI—which excludes food and energy prices—increased at an annual rate of 6.2%. Thus, with inflation far above the FOMC’s 2% target,The FOMC prefers to track inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditures price index, which tends to produce modestly lower inflation rates than does the CPI. the committee has increased its target range for the federal funds rate by 375 basis points since March 2022, and it now stands at 3.75% to 4%. Policymakers have signaled that further increases in the target range are likely.

The SPF consensus predicts that both headline and core CPI inflation will slow sharply in 2023—headline inflation from a projected 7.7% in 2022 to 3.4% in 2023 and core inflation from a projected 6.3% in 2022 to 3.5% in 2023. That inflation is expected to slow is heartening. But policymakers know that the outlook for inflation is highly uncertain and that forecasts for it have gone awry over the past year or so.

The Fed’s policy actions have weighed on the demand for interest rate-sensitive goods and services and on financial asset prices. For instance, since the beginning of 2022 (through Nov. 21):

- Equity prices have fallen by 19%.

- The 30-year conventional mortgage rate has increased by 340 basis points.

- The credit risk spread (the yield differential between BAA-rated corporate bonds and the 10-year Treasury note) has increased by 21 basis points.

Housing sales and construction have also turned lower; real residential fixed investment decreased at annual rates of 3.1%, 17.8% and 26.4% through the first three quarters of 2022, respectively. Moreover, house prices are beginning to soften, although they remain well above where they were before the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, homebuilder sentiment is at levels last seen in early 2020 during the pandemic’s onset.

Growth of real consumer outlays remained positive through the first three quarters of the year, largely because expenditures on services continued to increase at healthy rates. By contrast, spending on durable goods, which tend to be more discretionary and interest rate-sensitive, fell in the second quarter and third quarter of 2022. However, domestically produced lightweight vehicle sales (passenger cars and light trucks) increased in September and rose further to a 17-month high in October. Moreover, auto production has increased 21.6% year to date. Manufacturers are striving to meet existing demand and to replenish depleted dealer inventories. Outside of autos, October retail sales were much stronger than expected in inflation-adjusted terms, spurring some forecasters to boost their tracking forecast for real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2022.

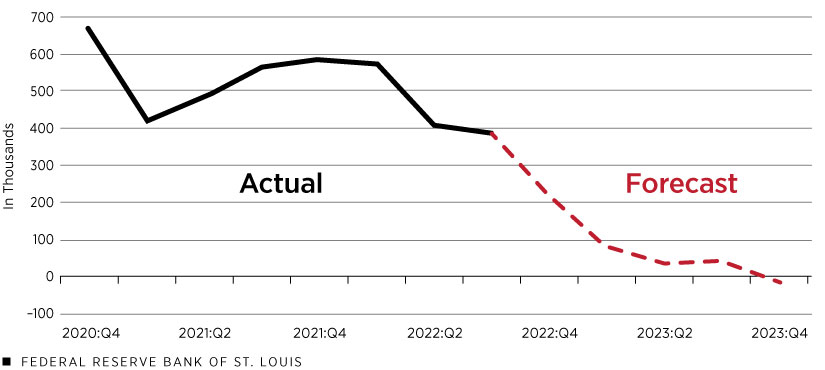

The labor market has thus far remained impervious to this year’s below-trend GDP growth. In October, nonfarm payrolls rose by 261,000, and the economy has added a total of 4.1 million jobs year to date, or about 407,000 per month. Although the unemployment rate ticked up from 3.5% in September to 3.7% in October, it remains historically low. Key labor market fundamentals—such as underlying growth in the labor force and recent trends in the labor force participation rate—suggest that the pace of job gains will slow in 2023. Indeed, as the following figure shows, the SPF consensus forecast is that job gains will only average 36,000 per month in 2023. For now, though, job openings have exceeded the 10 million mark for 15 months straight—a signal that firms still want to hire. In short, there is scant evidence of recessionary conditions based on current labor market conditions and recent trends in household consumption.

Monthly Average Increase in U.S. Nonfarm Payroll Employment

SOURCE: Survey of Professional Forecasters, November 2022.

NOTE: Figure data for the fourth quarter of 2022 to the fourth quarter of 2023 is forecasted.

Strong labor markets have been a boon to workers, but compensation has not kept pace with inflation. In the third quarter of 2022, the employment cost index was up 5% from a year earlier in nominal terms, but when adjusted for inflation, labor compensation declined by about 1.25%. Many consumers have maintained their normal expenditure patterns through increased debt and by using savings they accumulated during the pandemic. Unless real wages rise, there is a limit to the amount of debt consumers can absorb, at which point consumption spending would probably decline. In that event, business sales, corporate earnings and business capital spending would also fall. Falling corporate earnings would tend to lower stock (equity) prices.

The Economic Outlook

The outlook for the economy in 2023 has dimmed appreciably over the past year. In November 2021, the SPF consensus expected real GDP growth to average 2.6% in 2023 and the unemployment rate to average 3.6%. The current SPF forecast for 2023 is that real GDP will increase by 0.8% and the unemployment rate will average 4.2%. With average real GDP growth close to zero thus far in 2022, another economic shock could push the economy into a recession. Indeed, some economists expect a recession in 2023 because of the need for further interest rate hikes to bring inflation back to the FOMC’s 2% target. In his Nov. 2, 2022, press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged that the path to a soft landing has narrowed.

In conclusion, the balance of risks facing the economy over the near term are decidedly weighted to the downside. Still, forecasts and financial market indicators are not foolproof. The exceptional strength of the labor market testifies to a resilience that stands in stark contrast to weakness in other areas of the economy.

Notes

- See figure 4.D. from the FOMC’s September 2022 Summary of Economic Projections (PDF).

- The FOMC prefers to track inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditures price index, which tends to produce modestly lower inflation rates than does the CPI.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us