Labor Constraints Remain Greatest Challenge for Resurgent Manufacturing Sector

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- A pandemic-related surge in demand for durable goods and other factors helped push U.S. manufacturing output higher in 2022 than it was before the COVID-19 recession.

- Overall, U.S. manufacturing added roughly 1 million workers between 2010 and 2021, suggesting that the sector’s long-term decline in employment may have reversed.

- In an environment where many manufacturers are weighing whether to reshore production, labor shortages may be the greatest long-term obstacle to the sector’s growth.

In April 2022, U.S. industrial production and capacity utilization reached their highest levels since before the Great Recession of 2007-09. This resurgence in U.S. manufacturing output followed a surge in demand for products like appliances, furniture and building materials that began during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people remained at home and international supply chains struggled. Consumption of durable goods in May 2022 was 19% higher than pre-pandemic levels after adjusting for inflation.

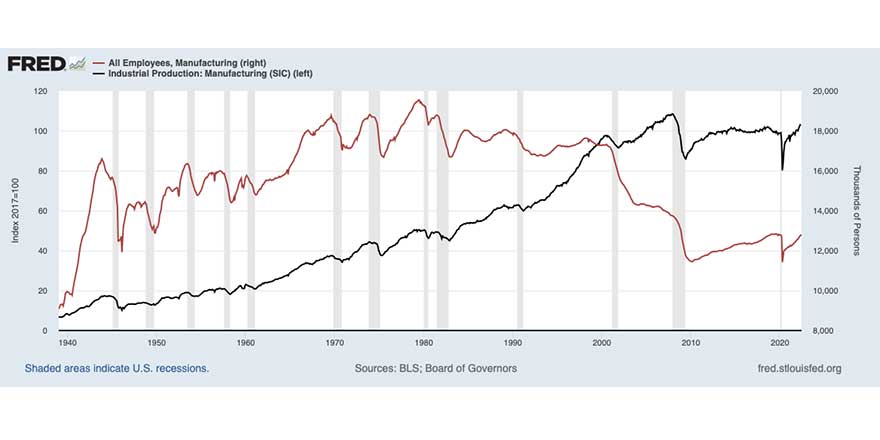

Rising trade tensions over the past decade and recent global supply chain disruptions also led firms to consider shifting back to domestic production and sourcing from domestic suppliers. Manufacturing employment in the U.S. economy peaked in 1979 at almost 20 million workers. In subsequent years, the U.S. economy shed manufacturing jobs, reaching a low in 2010 of 11.5 million workers after the Great Recession (and, temporarily, 11.4 million workers during the 2020 COVID-19 shutdowns). However, as the following figure shows, the sector added about 1 million workers between 2010 and 2021, suggesting the long-term decline may have reversed.

Manufacturing Comprises a Large Share of the Economy

One of the defining characteristics of the post-World War II economy has been the steadily shrinking share of workers in manufacturing. This, along with the rise in manufactured imports, is often cited as evidence of U.S. manufacturing’s decline. However, the share of the nation’s real gross domestic product (GDP) from manufacturing has remained stable at about 13% of national output since 1947 due to rapid productivity gains in the sector.See the 2017 On the Economy blog post “Is U.S. Manufacturing Really Declining?” by YiLi Chien and Paul Morris.

The table below summarizes manufacturing’s share of employment and output for the U.S. and states in the Eighth Federal Reserve District for the first quarter of 2007 (prior to the Great Recession) and the first quarter of 2022. Because of the capital-intensive nature of the sector, it’s not surprising that the share of output from manufacturing is notably larger than the share of workers.

For example, 12% of U.S. output in the first quarter of 2022 was from manufacturing, while the sector employed only 8.4% of the workforce. The manufacturing sector has more significant presence among Eighth District states, with output and employment shares both higher than the national average. This is most notable in Indiana, where manufacturing comprises 29.1% of the state’s output.

| U.S. | AR | IL | IN | KY | MS | MO | TN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007:Q1 | ||||||||

| Share of employment | 10.2% | 16.1% | 11.4% | 18.5% | 13.9% | 14.9% | 11.0% | 13.8% |

| Share of real GDP | 13.0% | 17.6% | 13.5% | 28.8% | 18.8% | 17.3% | 13.8% | 16.3% |

| 2022:Q1 | ||||||||

| Share of employment | 8.4% | 12.3% | 9.4% | 17.0% | 12.4% | 12.9% | 9.4% | 11.2% |

| Share of real GDP | 12.0% | 15.6% | 14.0% | 29.1% | 19.1% | 16.7% | 12.4% | 15.9% |

| SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations. | ||||||||

Between 2007 and 2022, the share of the workforce employed in the manufacturing sector declined nationally and among all Eighth District states. The manufacturing share of national output declined slightly from 13% to 12%. However, Eighth District data were mixed, with output shares increasing in Indiana, Illinois and Kentucky and declining in the other states. As discussed in the next section, much of this decline in manufacturing output occurred during the Great Recession of 2007-09 and not during the 2020 COVID-19 recession.

Impact of Recent Recessions on the Manufacturing Sector

As this article’s first figure shows, U.S. manufacturing employment declined by 2.3 million jobs during the Great Recession, accounting for about 1 in 4 jobs lost during the period. The recovery from the Great Recession marked a notable shift in manufacturing workers’ job prospects. While manufacturing employment never again reached 2007 levels, the 2010-19 period signifies the first time since the mid-1990s that the sector steadily increased employment.

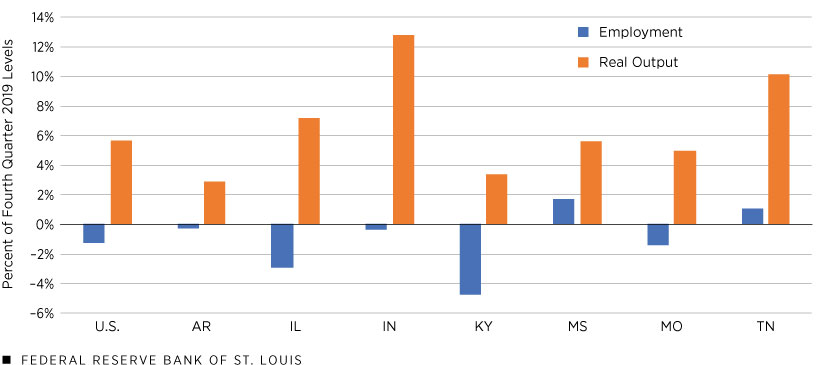

The sector fared comparatively better during the 2020 COVID-19 recession; U.S. manufacturing employment declined by 1.4 million jobs, accounting for roughly 1 in 20 jobs lost during the period. It appears that momentum has continued into the post-pandemic economy as well; since the recession ended in 2020, the manufacturing sector has added around 1.3 million jobs. This placed the first quarter 2022 manufacturing employment level just 1.3% below its pre-pandemic peak, as indicated in the following figure. Strong growth in consumer demand for goods, such as appliances, furniture and automobiles, partially accounts for the quick rebound in post-pandemic employment.

Manufacturing Recovery from the 2020 Recession: Change in Employment and Real Output

SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

NOTES: The figure compares the fourth quarter of 2019 with the first quarter of 2022. Measured quarterly, the U.S. economy’s peak expansion before the COVID-19 recession occurred in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Overall manufacturing output gains have been stronger than the labor market recovery, despite supply-chain disruptions and strong price inflation.See the 2022 Economic Synopses article “Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation during COVID-19” by Ana Maria Santacreu and Jesse LaBelle. Output by domestic producers is almost 6% higher than before the pandemic, as the figure above also illustrates. A similar trend emerges across Eighth District states, with employment in most regions near pre-pandemic levels, and output growth notably stronger.

Industry Outlook

The recent resurgence of the domestic manufacturing sector stands out as one of the U.S. economy’s bright spots in recent years; the long-term decline in the sector’s employment appears to have ended in 2010 as manufacturing productivity growth has slowed. The near-term outlook for the sector remains optimistic; many manufacturers continue to report significant order backlogs that will drive their business activity into early 2023, particularly among firms supplying building materials.

The sector faces some notable risks, however. First, international shipping costs remain significantly elevated, and missing key inputs (such as semiconductors) continue to disrupt domestic production, leaving some firms with elevated inventories.

Second, slowing global growth and the appreciation of the dollar could reduce demand for U.S. exports while increasing foreign competition. However, a stronger dollar could help offset the higher costs that the manufacturing industry has seen recently (with year-over-year prices as measured by the producer price index increasing 19% in May).

Third, U.S. consumers are expected to shift consumption back toward many of the services that they postponed or canceled because of the pandemic, like travel and health care. This shift back to services, along with higher prices eroding real household incomes, will likely slow demand for household goods.

Despite these risks, manufacturing contacts in the St. Louis Fed’s Beige Book indicate that labor shortages remain the greatest long-term obstacle to growth. In an environment of heightened global trade tensions and exacerbated international shipping bottlenecks, many firms are looking to reshore production. However, growth of the U.S. labor force is constrained by an aging U.S. population and historically low levels of international immigration.

As a result, some firms are actively taking steps to build the pipeline of future workers. For example, in western Tennessee, Ford is focusing its outreach efforts on eighth grade students who will be graduating from high school when its plant there begins producing batteries for electric vehicles.

Moreover, manufacturers are now facing increased competition for entry-level workers from sectors like retail and hospitality that raised wages significantly in recent years to attract workers and/or keep up with rising minimum wages. The wage premium for manufacturing jobs has disappeared. In 2010, the average manufacturing worker earned $0.50 more per hour than the average private sector worker; in 2022, the average manufacturing worker earns $1.12 less than the average private sector worker. This premium’s elimination was not due to falling wages in manufacturing, but faster wage growth in other sectors. Competition for workers has led some U.S. manufacturers to invest more heavily in automation, and according to one trade group, orders for industrial robots jumped significantly in 2021 and the first quarter of 2022.See The Wall Street Journal article “Robots Pick Up More Work at Busy Factories” from May 29, 2022.

Faced with higher material and labor costs, manufacturers have become more comfortable passing on higher prices to customers, in some cases shifting from annual price increases to biannual or even quarterly increases. Firms are also investing in new technologies to improve labor productivity, although these savings may be at a distant horizon. Supply-chain disruptions and higher costs have made much of this equipment less beneficial in the near term—although it remains a viable long-term solution.

Notes

- See the 2017 On the Economy blog post “Is U.S. Manufacturing Really Declining?” by YiLi Chien and Paul Morris.

- See the 2022 Economic Synopses article “Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation during COVID-19” by Ana Maria Santacreu and Jesse LaBelle.

- See The Wall Street Journal article “Robots Pick Up More Work at Busy Factories” from May 29, 2022.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us