GDP Growth, Decelerating Inflation in U.S. Economic Outlook

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The consensus forecast is that U.S. real GDP growth will return to positive territory following declines in the first and second quarters of 2022.

- Current inflation far exceeds the Fed’s 2% target, and while inflation is expected to continue decelerating, the medium-term outlook is uncertain.

- Strong job growth throughout the first seven months of 2022 and the July unemployment rate of 3.5% seem inconsistent with recessionary conditions.

Gross domestic product (GDP) data for the first half of 2022 appeared to suggest that the U.S. economy was either in or on the cusp of a recession. However, the demand for labor remained very strong over the first seven months of 2022, and consumer outlays continued to register positive growth over the first half of the year. But with inflation running at levels last seen in the early 1980s, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has signaled that it will continue to raise its federal funds rate target and reduce the size of its balance sheet, despite negative real GDP growth.

In response, the interest rate-sensitive housing sector continued to weaken, and equity prices declined sharply through late August. Although there remains considerable uncertainty about the macroeconomy and inflation over the second half of the year, the consensus of private forecasters is that real GDP growth will return to positive territory and the inflation rate will continue to decelerate.

The Macroeconomic Data: A Riddle, Wrapped in a Mystery, Inside an Enigma

U.S. real GDP declined in the first and second quarters of 2022, at annual rates of 1.6% and 0.6%, respectively. These declines caught many economists by surprise. Usually, two consecutive quarterly declines in real GDP are a reliable signal that the U.S. macroeconomy has fallen into a recession.

Indeed, there has been only one episode in the post-World War II period—the second and third quarters of 1947—in which two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth was not associated with a recession [as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee (NBER)].The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee is a group of academic economists that maintain the historical chronology of U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions. Not surprisingly, many professional forecasters now expect a recession sometime in the next 12 months. However, annual revisions to GDP data in late September suggest the possibility that the small declines in the first and second quarters of 2022 could be revised higher, given other data pointing to continued growth.

When determining monthly business cycle turning points in the economy, commonly called peaks and troughs, the NBER tends to focus on six monthly indicators that measure employment, production, sales and income at an economywide level. The NBER also tracks real GDP and real gross domestic income (GDI) to determine peak and trough quarters. Most of the monthly indicators that the NBER looks at continued to register positive growth through June or July, so the probability of a recession in June or July appears low.See my August 2022 On the Economy blog, “Dating Economic Recessions in Real Time Is a Challenge.” Moreover, growth of real GDI has been positive over the first half of 2022 (0.8% at an annual rate).

In that vein, strong job growth and a low unemployment rate are inconsistent with recessionary conditions. And robust job growth with low unemployment is precisely what has occurred over the first seven months of 2022: Nonfarm payrolls added 3.3 million jobs, about 471,000 per month. Strong job growth continues to keep the unemployment rate low; unemployment returned to its pre-pandemic level of 3.5% in July, its lowest point since December 1969. Other labor data, such as job openings, and anecdotal evidence recorded in the Beige Book suggest that many firms remain short-staffed. On one hand, this has impeded their ability to produce and sell as much as they had planned. On the other hand, many firms have had to raise wages and increase benefits to attract new workers and retain existing ones.

Many economic indicators have a reasonably good track record of predicting future recessionary conditions. Economists have known for quite some time that Treasury yield curve (or term spread) inversions tend to be reliable predictors of recessions.See my June 2018 Economic Synopses article, “Recession Signals: The Yield Curve vs. Unemployment Rate Troughs.” Inversions occur when the yield on short-term Treasury securities exceeds the yield on long-term Treasury securities. Some measures of the Treasury yield curve have already inverted, such as the 10-year and two-year Treasury yield curve and the 10-year and one-year Treasury yield curve. However, as of Aug. 25, another commonly used yield curve measure, the spread between the 10-year Treasury note and the three-month Treasury bill, has not inverted.

Inflation Is (Probably) Headed Lower, But How Low?

Inflation slowed to a crawl at the beginning of the third quarter of 2022, as a sharp decline in energy prices resulted in virtually no change in the consumer price index (CPI) in July compared with June. However, July’s tame CPI reading masks this year’s high inflation rate, which is the highest since 1982. Over the first seven months of 2022, headline CPI rose at a 9.4% annual rate, surpassing last year’s 7.1% annual increase and the meager 1.3% annual increase registered in 2020. (These 2021 and 2020 inflation rates were measured from December to December.) Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, increased a bit less through July, to 6.4%.

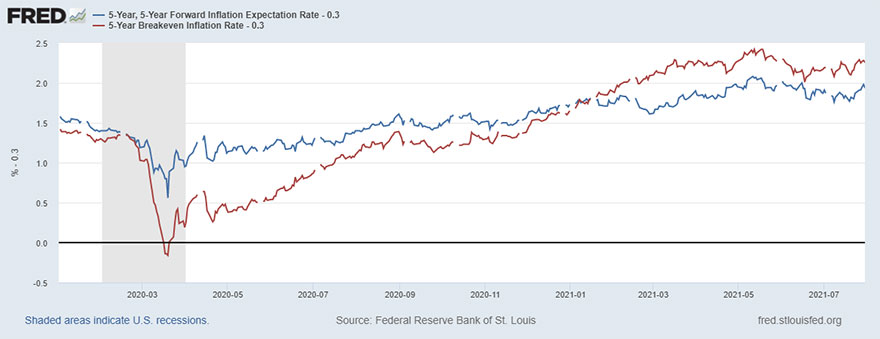

With headline and core inflation far above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target rate, the FOMC has increased its federal funds rate target by 225 basis points so far this year. Some FOMC participants believe that the federal funds rate target may eventually need to rise to 4% or higher to bring inflation back to its 2% target. A key part of this strategy is to keep long-run inflation expectations anchored at 2%.

The consensus of professional forecasters and financial market participants is that the FOMC will succeed in lowering inflation to 2%—though it will probably be a multiyear effort. In August, the consensus from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) was that the CPI inflation rate will decline from 7.5% in 2022 to 3.2% in 2023 and to 2.5% in 2024. The SPF also projected that the FOMC’s preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures price index, will decline from 5.8% in 2022 to 2.8% in 2023 and to 2.3% in 2024.These inflation forecasts predict the percent change in the personal consumption expenditures price index from the fourth quarter of one year to the fourth quarter of the following year.

The Consensus Outlook

According to the August Blue Chip Consensus, real GDP growth will average less than 1% annualized over the second half of this year and into the first half of 2023. The SPF consensus is a bit more optimistic; growth is forecast to average about 1.25% over the second half of 2022 and into the first half of 2023. Both sets of forecasters project a modest uptick in the unemployment rate over the following year, to 4%. While the expected return to positive GDP growth is heartening, heightened uncertainty about the outlook for medium-term inflation and the likelihood of further tightening actions by the FOMC suggests that risks to the macroeconomy remain tilted to the downside.

Notes

- The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee is a group of academic economists that maintain the historical chronology of U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions.

- See my August 2022 On the Economy blog, “Dating Economic Recessions in Real Time Is a Challenge.”

- See my June 2018 Economic Synopses article, “Recession Signals: The Yield Curve vs. Unemployment Rate Troughs.”

- These inflation forecasts predict the percent change in the personal consumption expenditures price index from the fourth quarter of one year to the fourth quarter of the following year.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us