Employment Effects of Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Benefits: Incentives Matter

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Emergency unemployment benefits were introduced early in the COVID-19 pandemic to ease its impact on the U.S. labor market. Over the next year, employment recovered considerably.

- A 2022 working paper from this article’s authors found that terminating emergency unemployment benefit programs caused a substantial increase in employment.

- An extension of the working paper’s analysis showed that halting these programs affected the employment of younger and older workers differently.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic fallout that followed in the spring of 2020, the federal government augmented the standard unemployment insurance system with several emergency unemployment benefits (EUB) programs created through the CARES Act. The following table describes the EUB programs that we included in our analysis.

| Program | Description |

|---|---|

| Pandemic Unemployment Assistance | Provided unemployment benefits for self-employed and other unemployed people not typically eligible |

| Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation | Extended the duration of unemployment benefits by up to 53 weeks |

| Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation | Added $600 a week (later $300) to regular state unemployment insurance programs |

| SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor | |

The government intended these benefits to ease the negative impact that the pandemic, as well as the resulting policy response (such as mandated shutdowns) and change in households’ purchasing patterns, had on the labor market. The EUB programs were established under the CARES Act in March 2020, and an extension to the original legislation ultimately set them to expire in September 2021.

Over the year following the introduction of these benefits, employment recovered substantially but not completely. By May 2021, seasonally adjusted job openings reached all-time highs (according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) while employment growth began to slow. In response, roughly one-half of all U.S. governors announced plans to end some or all of the EUB programs in their respective states in advance of the September 2021 termination date. In the end, 26 states ended EUB programs before September 2021, with 24 states doing so between June 12 and July 3.

Terminating Emergency Unemployment Benefits Increased Employment

In a recently released working paper, we estimated the causal effect on state employment of ending emergency unemployment benefits using the EUB programs’ termination dates as an exogenous source of variation. See our 2022 working paper “The Jobs Effect of Ending Pandemic Unemployment Benefits: A State-Level Analysis,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2022-010A. In the working paper, we noted that a key factor in whether a state halted benefits early was the political party of its governor. Using political considerations as a source of random assignment—useful for inferring causal effect—has a rich history in empirical economics.

We found that reducing EUB rolls through program termination caused a substantial increase in employment. Over a three-month horizon, for every 100-person reduction in beneficiaries because of EUB program termination, employment increased by about 37 people. This result was very unlikely to have occurred by chance, and it was not strongly dependent on any particular assumption. In other words, we could have changed our procedures in many ways and obtained the same result.Statisticians describe results that are very unlikely to have occurred by chance as “statistically significant.” For example, the result held if we controlled for the number of monthly COVID-19 cases in each state.

EUB programs permitted many recipients to collect unemployment benefits close to or above their pre-pandemic wage. Therefore, many recipients had little or no monetary incentive to work. Termination of a state’s EUB programs cut or eliminated such generous benefits for many, which effectively restored the incentive for many to work. Perhaps the most fundamental postulate of economics—that people respond to incentives—set in, and employment increased substantially in the state over the following few months.Newly incentivized unemployed individuals encountered a record number of job openings in the summer and fall of 2021.

Employment Effect Differed by Age Group

In this article, we extend the working paper’s analysis to consider the EUB programs’ employment effect for three different age ranges:

- 18 to 30 years old

- 31 to 54 years old

- 55 years and older

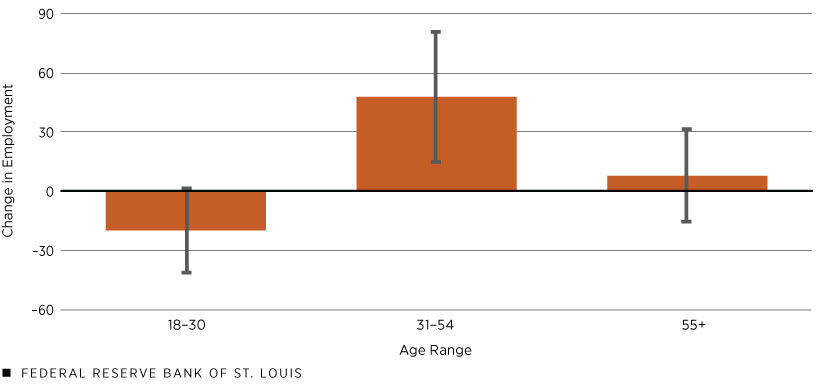

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey provides data on monthly employment, age, labor force status and state of residency, and the Department of Labor provides data on the number of unemployment program beneficiaries.For additional details about the data we used, see Section 3 of our previously mentioned working paper. Using an econometric procedure, we estimated how a reduction in the number of EUB program beneficiaries affected employment levels across the entire sample of states.Unobserved economic factors that drive state-level employment growth are also likely to influence the number of beneficiaries on unemployment rolls. For example, particularly bad weather in a state during a month might both reduce employment growth and unemployment claims. This generates a potential problem, or bias, that might arise and complicate interpretation of our results; however, the differential stopping months for EUB programs across U.S. states permits us to use an instrumental variable technique to circumvent this issue. The following figure illustrates our results.

3-Month Change in Number of People Employed per 100-Person Reduction in Emergency Unemployment Beneficiaries

SOURCES: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey, U.S. Department of Labor and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Employment change follows EUB programs’ termination in 2021. Regression weighted by state-level pre-pandemic employment (January 2020). Vertical lines indicate 90% confidence intervals.

Employment for the middle group, which in our analysis comprised those from ages 31 to 54, showed the largest response. Employment in this age group increased by 47.5 people for every 100-person reduction in EUB recipients, indicating the strong, positive jobs effect that terminating benefits had on those in the middle of the age distribution.

Employment for younger workers, those from ages 18 to 30 in our analysis, tends to increase in the summer and decrease in the fall. Because the termination of benefits had a summer (for states halting their EUB programs earlier) and fall (for states halting their EUB programs later) pattern, disentangling seasonal effects from the jobs effect presents a challenge that we will not address in this article.

The estimate for the oldest group was positive; however, it was close enough to zero that it fairly easily might have occurred by chance. One potential reason for the small effect among older workers was that, upon losing benefits, older individuals might have chosen to exit the labor force for retirement instead of becoming employed.

Much work remains for researchers studying this episode. Understanding the impact of unemployment benefits termination on, for example, job openings, quits, hires and labor force participation is likely a fruitful area for investigation.

Notes

- See our 2022 working paper “The Jobs Effect of Ending Pandemic Unemployment Benefits: A State-Level Analysis,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2022-010A.

- Statisticians describe results that are very unlikely to have occurred by chance as “statistically significant.”

- Newly incentivized unemployed individuals encountered a record number of job openings in the summer and fall of 2021.

- For additional details about the data we used, see Section 3 of our previously mentioned working paper.

- Unobserved economic factors that drive state-level employment growth are also likely to influence the number of beneficiaries on unemployment rolls. For example, particularly bad weather in a state during a month might both reduce employment growth and unemployment claims. This generates a potential problem, or bias, that might arise and complicate interpretation of our results; however, the differential stopping months for EUB programs across U.S. states permits us to use an instrumental variable technique to circumvent this issue.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us