Measuring the Fed’s Monetary Policy Stance during COVID-19

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The addition of bond purchases and forward guidance to the Fed’s traditional short-term interest rate instrument suggests the need for a new, combined measure of monetary policy settings.

- Monetary policy’s impact on the economy will depend on both the Fed’s instrument settings and on the economy’s current condition.

- The COVID-19 period illustrates how important it is to consider both factors (instrument settings and economic windspeed) when gauging the stance of monetary policy.

The Federal Reserve Act instructs the Federal Reserve to use monetary policy to promote maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.See Section 2A, "Monetary Policy Objectives," in the Federal Reserve Act. In practice, the Fed “leans against the economic wind,” tightening policy when inflation threatens the economy and easing policy when the economy weakens. This article explains one way to gauge the stance of monetary policy; that is, how to measure the Fed’s instrument settings in light of the economic wind.

Measuring Monetary Policy Settings

Since 2008, the Fed has conducted monetary policy using both conventional and unconventional tools.See “Policy Tools.” Managing short-term interest rates serves as the Fed’s key conventional tool while purchasing longer-term bonds and forward guidance have been its main unconventional tools.

When the Fed is implementing conventional policy, analysts commonly use the level of short-term interest rates to (crudely) measure the stance of policy. High short-term interest rates tend to contract economic activity while low short-term interest rates tend to do the opposite.

While short-term interest rates controlled by the Fed continue to serve as an important measure of monetary policy,See “Monetary Policy Principles and Practice.” extended spells at the effective lower bound of interest rates, combined with new monetary policy tools, mean that we need a summary measure of monetary policy’s combined settings to gauge the stance of policy.The lower limit of the federal funds rate target range was zero between Dec. 16, 2008, and Dec. 16, 2015, and again between March 16, 2020, and March 16, 2022.

One such measure of monetary policy is the “shadow” federal funds rate.See Jing Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia, “Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 48, Nos. 2-3, March-April 2016. See the Atlanta Fed for more explanation and the current shadow rate. Based on a model of interest rates of many maturities, the shadow rate is an estimate of what the Fed’s overnight interest rate would be if the FOMC extended its policy range below zero, which it currently does not do. This captures how the Fed’s non-interest rate tools, including large-scale asset purchases and forward guidance, affect the current and expected future path of the federal funds rate.

Yet the neutral level of the federal funds rate—one that cannot be characterized as either tight or loose—changes over time. Thus, whether a given interest rate level stimulates or contracts economic activity depends on its relation to this moving target.

One approach to estimating the long-term neutral rate is to look for an indicator in financial markets that suggests what the short-term rate will be far in the future, after any current economic squalls have passed.See Michael D. Bauer and Glenn D. Rudebusch, “Interest Rates Under Falling Stars,” American Economic Review, Vol. 110, No. 5, May 2020. A long-term Treasury forward rate is precisely such an indicator: It is related to the short-term interest rate expected to prevail at a particular date in the future, derived from market prices today.

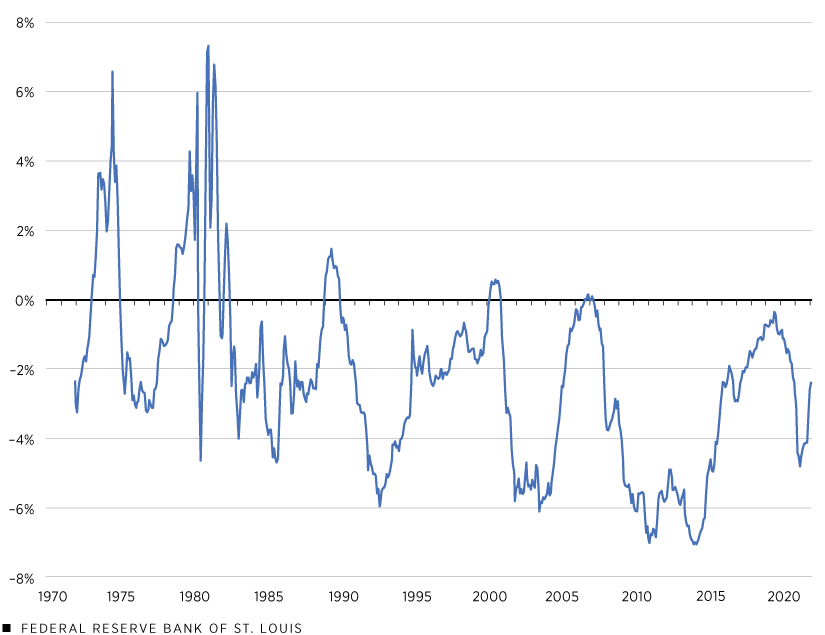

Comparing the federal funds rate or a shadow federal funds rate to a long-term Treasury forward rate therefore allows us to characterize the degree of tightness or ease the Fed is applying to the economy if one assumes current conditions are average or normal. But, of course, current conditions may not be average, as the next section explores. The figure below shows how this measure of the Fed’s monetary policy settings has varied each month between December 1971 and December 2021.

A Measure of Monetary Policy Settings: Federal Funds or Shadow Rate Minus Neutral Rate

SOURCES: Federal Reserve Board, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and author’s calculations.

NOTES: The figure shows a monthly measure of the Fed’s monetary policy settings between December 1971 and December 2021. The line shows the difference between the federal funds rate, when the lower limit of the Fed’s target range is above zero, and the 15-year Treasury forward rate, which serves as a proxy for the neutral rate. The shadow federal funds rate is substituted for the federal funds rate when the lower limit of the federal funds target range equals zero. In the figure, upward movements indicate tightening of monetary policy, while downward movements indicate easing of policy. Tighter policy is expected to slow the economy while easier policy is expected to strengthen the economy.

Measuring the Strength of the Economy

The impact of monetary policy on the economy depends both on how tight or easy the Fed’s policy settings are at any time (as shown in the figure above) and on the economy’s condition. If the economy is very weak—for example, with the unemployment rate in double-digits—then an accommodative monetary policy is likely to be appropriate, with the federal funds (or shadow) rate well below the neutral rate. The Fed’s lean-against-the-wind policy attempts to counteract the economy’s weakness. If the economy is very strong—for example, with a very low unemployment rate and rising inflation—the Fed is likely to set the federal funds rate closer to, or even above, the neutral rate.

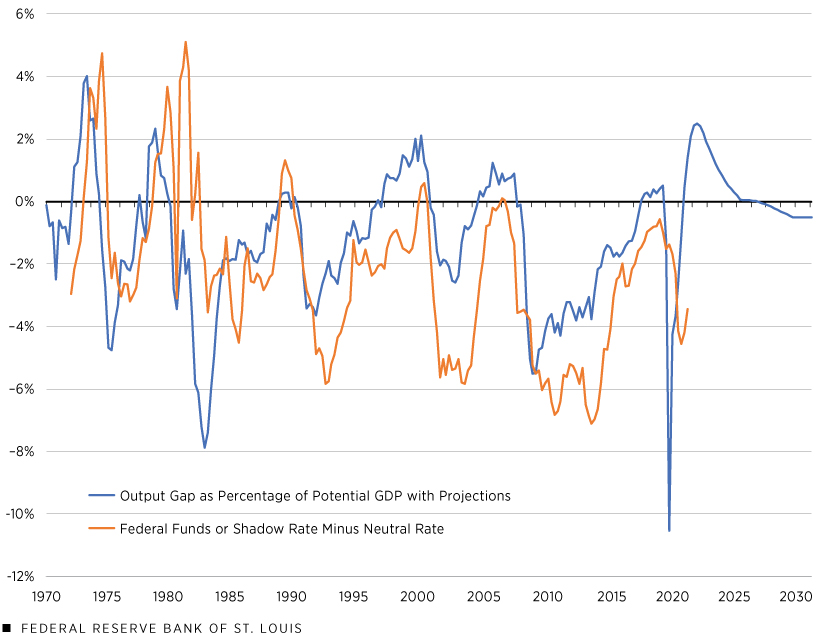

The figure below compares the summary measure of Fed policy described above to the output gap, i.e., the strength of the economy.The output gap is the difference, in percent, between the current actual and the current hypothetical full-employment level of output. See the section “Budget and Economic Data” on the Congressional Budget Office’s website for an explanation of potential real GDP and the output gap. The Fed’s monetary policy settings track the state of the economy. When the output gap is positive—which occurs near business-cycle peaks—the Fed runs a tighter monetary policy. Conversely, when the output gap is negative—when the economy is in or recovering from a recession—the Fed sets a looser monetary policy. Again, this is how the Fed leans against the economic wind: The central bank exerts restraint when the economy is very strong and provides support when it is very weak.

A Measure of Monetary Policy Settings and the Economy’s Output Gap

SOURCES: Federal Reserve Board, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Congressional Budget Office and author’s calculations.

NOTES: The figure shows a quarterly measure of the Fed’s monetary policy settings between the first quarter of 1972 and the fourth quarter of 2021 and the CBO’s estimate of the economy’s output gap between the first quarter of 1970 and the fourth quarter of 2021, along with CBO projections for the subsequent decade. The measure of the Fed’s monetary policy settings is explained in the notes to the first figure. The output gap is the percentage difference between actual real GDP and the CBO’s estimate of potential real GDP.

Combining the Fed’s Instrument Settings and the Economic Windspeed: The Stance of Monetary Policy

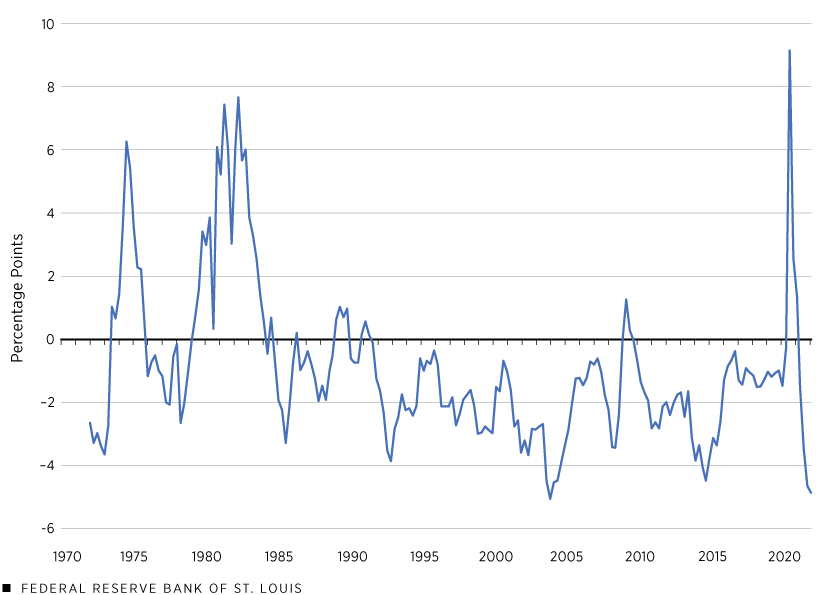

The figure below characterizes the stance of Fed monetary policy since the beginning of 1972. The line represents the difference between the monetary policy settings and the economy’s output gap at a quarterly frequency. For example:

- When the stance is zero, monetary policy approximately offsets the economy’s strength or weakness.

- When the stance is positive, monetary policy is restrictive or tight, with the degree of restraint exceeding the strength of the economy.

- When the stance is negative, monetary policy is accommodative or easy, with the degree of ease exceeding the weakness of the economy.

The Stance of Monetary Policy: Fed’s Instrument Settings Relative to Economic Conditions

SOURCES: See figures above for data sources.

NOTES: The figure shows the quarterly difference between the measure of monetary policy settings described in the text and the economy’s output gap between the first quarter of 1972 and the fourth quarter of 2021. The line represents the stance of monetary policy, which combines the settings of monetary policy and the strength of the economy. Upward movements in the figure represent a tighter stance of policy, while downward movements represent a looser stance of policy.

The Stance of Monetary Policy Has Fluctuated Significantly during the Pandemic

According to the measure in the figure, the most restrictive stance of monetary policy in the last 50 years occurred in the second quarter of 2020, when the COVID-19 crisis had its maximum impact. The economy was very weak, with real GDP some 10.5% below its potential. Although the Fed eased monetary policy aggressively using several of its tools, it was not enough to counteract the economy’s weakness.

Conversely, one of the most accommodative stances of monetary policy since 1972 occurred in the fourth quarter of 2021. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate, the economy had completely recovered by the third quarter of 2021, and was 1.4% above its potential in the fourth quarter of that year. Monetary policy settings, meanwhile, remained relatively easy.

The COVID-19 period illustrates how important it is to measure both the Fed’s monetary policy settings and the economy’s current condition to gauge the stance of monetary policy. Even though the Fed did not change its target range for the federal funds rate between mid-March 2020 and mid-March 2022, the ultimate impact of monetary policy on the economy fluctuated dramatically. Thus, it’s important to gauge monetary policy against the strength of the economy and adjust accordingly.

Endnotes

- See Section 2A, "Monetary Policy Objectives," in the Federal Reserve Act.

- See “Policy Tools.”

- See “Monetary Policy Principles and Practice.”

- The lower limit of the federal funds rate target range was zero between Dec. 16, 2008, and Dec. 16, 2015, and again between March 16, 2020, and March 16, 2022.

- See Jing Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia, “Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 48, Nos. 2-3, March-April 2016. See the Atlanta Fed for more explanation and the current shadow rate.

- See Michael D. Bauer and Glenn D. Rudebusch, “Interest Rates Under Falling Stars,” American Economic Review, Vol. 110, No. 5, May 2020.

- The output gap is the difference, in percent, between the current actual and the current hypothetical full-employment level of output. See the section “Budget and Economic Data” on the Congressional Budget Office’s website for an explanation of potential real GDP and the output gap.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us