The Market for Eggs: How Prices Are Hatched

—Headline from the Butler Eagle (PA), December 28, 2022

If you’ve bought a dozen eggs recently, you might have noticed that prices have taken a sharp turn higher, making your omelet seem like a luxury. Eggs play an important role in the culinary lives of many people, from serving as a breakfast staple to being a key ingredient in countless recipes. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the American consumer eats 250-300 eggs per year on average. So when their price fluctuates, people notice. Since the summer of 2024, the price of eggs has more than doubled in some places, with consumers paying more than $6 per dozen in March 2025, according to the Associated Press.

What’s behind the sharp increase? As with many things in economics, it all boils down to supply and demand—where the short shelf life of eggs, the egg production cycle of hens, and consumer habits all play a role in cracking the price puzzle.

Where Do Egg Prices Come From?

The price of eggs, as with most goods and services, is determined in a market made up of consumers and producers. And, eggs have a surprisingly sophisticated marketplace, aptly named the Egg Clearinghouse, Inc. (ECI), where billions of eggs are traded every year. In 2024, 2.6 billion eggs and 39 million pounds of egg product, valued at more than $600 million, were traded on its online platform.

Specifically, ECI helps large-volume egg suppliers fill in the gaps. For example, if a farmer is trying to fill a large order for a supermarket and comes up a little short, they can use the exchange to buy enough eggs to fill the gap. Likewise, other farmers might have excess eggs to sell on ECI. In this way, ECI helps establish the wholesale price of eggs, which informs the retail price, where it is passed on to consumers and businesses. And, of course, the price changes in real time as the market changes in response to shifting supply and demand. Speaking of supply and demand, let’s look at how the supply and demand for eggs determines their price.

The Demand and Supply of Eggs

The Demand Side

Economics is built on simple foundational principles such as the law of demand, which states that when the price of a certain good goes up, consumers buy a smaller quantity of that good. Despite rising egg prices, however, the quantity of eggs demanded by consumers has remained relatively steady over time, as shown in the table below. This is because eggs are a dietary staple: Even at their current high prices, eggs remain a relatively small portion of people’s food budgets, and there are few good substitutes. This suggests that eggs have relatively inelastic demand, which means that people don’t reduce their consumption very much as the price rises. Data and research from the American Journal of Public Health support the idea that demand is relatively inelastic.

| Year | Eggs per person | |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 249 | |

| 2022 | 281 | |

| 2021 | 286 | |

| 2020 | 288 | |

| SOURCE: “Shell Eggs from Farm to Table.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service. Last updated November 20, 2024. | ||

The Supply Side

Likewise, the law of supply teaches us that when the price of a good goes up, producers supply a greater quantity of that good. There’s less research on the elasticity of supply of eggs, but let’s consider some of the factors that contribute to how quickly suppliers respond to a change in price.

Unlike a manufactured good, where output can often be increased by turning a dial or reprioritizing resources, chickens have an incubation period, literally; a commercial laying hen takes about 18 to 22 weeks to mature before they can start laying eggs and are kept for 2-3 years. On top of that, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration notes that eggs have a shelf life of three weeks, which means that it’s hard to build up inventory. As such, let’s assume that eggs have relatively inelastic supply in the short-run; this means producers don’t (or cannot) increase the quantity they supply very much relative to the increase in price. In the long-run, supply is more elastic because farmers can adjust their flock sizes, invest in larger facilities, expand production, or even vaccinate their chickens. And, in the long-run, if prices remain high, new firms (farms) can enter the market.

Why Does Elasticity Matter?

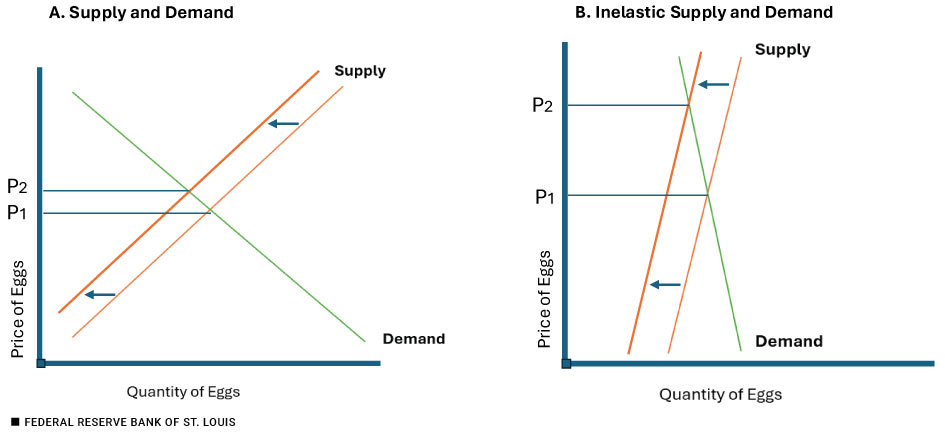

Let’s take a textbook approach to elasticity. Figure 1 below shows standard supply and demand curves in the left panel and a similar graph with relatively inelastic supply and demand curves in the right panel. The result of having inelastic supply and demand curves with this more steeply sloped, vertical shape is that changes in either supply or demand result in relatively larger changes in price. Let’s compare the left and right panels. The supply curve has shifted leftward by the same quantity in both graphs, but there is a much larger change in price for the graph with inelastic supply and inelastic demand. This relationship shows how small changes in supply, when it’s inelastic, can result in much larger changes in price.

Figure 1: Inelastic Supply and Demand

Enter Avian Flu

Avian flu was first detected in 2016, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control; it was first detected in a commercial flock in February 2022. When avian flu is detected in a flock of chickens, the farmer must quarantine and humanely euthanize the entire flock. Its effects have been devastating: More than 168 million egg-laying hens have been killed since 2022, with 55 million chickens killed in 2024 and 30 million killed in just the first two months of 2025.

Avian flu itself seems to target egg-laying hens: Per the February 2025 Yahoo News article, “Egg Prices Are Surging, So Why Are Chicken Prices Stable?” more than 75% of the losses have been among egg-laying hens, with just 9% among chickens used for meat (“broilers”). This helps explain the differences shown in the Figure 2 FRED graph below.

Figure 2: Chicken or Egg?

![FRED graph data series [APU0000706111] and [APU0000708111] for 2000-01-01 to 2025-03-01.](/-/media/project/frbstl/stlouisfed/publications/page-one/images/uploads/2025/2025-may-poe-fig2.png?sc_lang=en&hash=F302D5B90AC1E5736FF896851FD2AD1B)

NOTE: Since the avian flu outbreak in 2022, egg prices have been more volatile and have risen more sharply than chicken prices.

SOURCE: Average Prices: Chicken, Fresh, Whole (Cost per Pound) and Eggs, Grade A, Large (Cost per Dozen) in U.S. City Average, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; accessed April 10, 2025.

As farmers who have lost chickens attempt to fulfill orders and contracts, they have relied heavily on ECI. One farmer may have had to put much of his chicken flock down because of avian flu but needs to fulfill an order of 20,000 eggs for a major grocery chain. If other farmers are facing similar situations and millions of chickens have had to be euthanized, there will be many more people looking to buy than sell in the ECI marketplace: Fewer chickens mean fewer eggs, resulting in a leftward shift of the supply curve and higher prices.

Conclusion

The egg market provides a compelling example of how supply and demand interact to determine prices. ECI plays an important role (1) by helping suppliers efficiently meet large orders and (2) in setting wholesale prices, which influences retail prices. Recent events, such as the avian flu outbreak that reduced the chicken population, have disrupted supply and led to sharp price increases: The USDA projects egg prices will rise another 41% in 2025.

Inelastic demand: The type of demand that exists when the percentage change in quantity demanded is less than the percentage change in price; that is, consumers are not very sensitive to a change in the price of a good or service.

Inelastic supply: The type of supply that exists when the percentage change in quantity supplied is less than the percentage change in price; that is, producers are not very sensitive to a change in the price of a good or service.

Law of demand: As the price of a good or service rises, the quantity demanded of that good or service falls. Likewise, as the price of a good or service falls, the quantity demanded of that good or service rises.

Law of supply: As the price of a good or service rises, the quantity supplied of that good or service rises. Likewise, as the price of a good or service falls, the quantity supplied of that good or service falls.

Long-run: In microeconomics, a business planning period in which the quantities of all inputs are variable.

Short-run: In microeconomics, a business planning period in which the quantities of some inputs are fixed while the quantities of other inputs are variable.

Andreyeva, Tatiana; Long, Michael W. and Brownell, Kelly D. “The Impact of Food Prices on Consumption: A Systematic Review of Research on the Price Elasticity of Demand for Food.” American Journal of Public Health, 2010, 100(2), pp. 216-22.

“Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Commercial and Backyard Flocks.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service. Last modified June 20, 2024.

Dorn, Andrew. “Egg Prices Are Surging, So Why Are Chicken Prices Stable?” Yahoo News, February 14, 2025.

“Food Price Outlook, 2025.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Updated March 25, 2025.

Funk, Josh and Durbin, Dee-Ann. “US Egg Prices Increase to Record High, Dashing Hopes of Cheap Eggs by Easter.” Associated Press, April 10, 2025.

“Questions and Answers on Avian Influenza (‘Bird Flu’).” National Chicken Council.

“Shell Eggs from Farm to Table.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service. Last updated November 20, 2024.

Stuttgen, Sandra. “Life Cycle of a Laying Hen.” University of Wisconsin-Madison, Livestock Division of Extension.

Thomas, Patrick. “At the ‘Wall Street of Eggs,’ Demand Is Surging.” Wall Street Journal, February 18, 2025.

“USDA Reported H5N1 Bird Flu Detections in Poultry.” U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).

“What You Need to Know About Egg Safety.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated March 5, 2024.

Citation

Scott A. Wolla, ldquoThe Market for Eggs: How Prices Are Hatched,rdquo Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Page One Economics, May 9, 2025.

These essays from our education specialists cover economic and personal finance basics. Special versions are available for classroom use. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us