A New Frontier: Monetary Policy with Ample Reserves

—FOMC Statement, March 20, 2019.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the United States. Its dual mandate from Congress is to promote maximum employment and price stability. To achieve this mandate, the Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy by influencing market interest rates. However, the means by which the Federal Reserve influences interest rates have changed over time.

Influencing the Economy through the Federal Funds Rate

For decades prior to 2008, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would adjust monetary policy to match economic conditions by raising or lowering its target for the federal funds rate (FFR), the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans.1 The Fed can influence the general cost of borrowing through this one rate because, although short-term interest rates differ from each other, they are closely linked.2 If one short-term rate gets much below others, financial institutions will tend to borrow in that market and lend where rates are higher. This tendency puts upward pressure on the lower rate and downward pressure on the higher rate—keeping rates linked. This is known as arbitrage, an important aspect of the way financial markets, and monetary policy, work. So, by influencing one rate—the FFR—the Federal Reserve can influence other short-term rates, which affect longer-term interest rates, consumer and producer decisions, and ultimately the level of employment and inflation in the U.S. economy (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Transmission of Monetary Policy

Monetary Policy with Scarce Reserves

Prior to September 2008, the Federal Reserve primarily bought and sold relatively small quantities of Treasury securities in the open market, termed open market operations, to adjust the level of bank reserves and thereby influence the FFR. Bank reserves are the sum of cash that banks hold in their vaults and the deposits they maintain at Federal Reserve Banks. Reserves fall into two categories. First, banks hold required reserves, funds that must be held as vault cash or deposits at a Federal Reserve Bank.3 And banks can also hold excess reserves, funds held as vault cash or deposits at a Federal Reserve Bank in excess of required reserves. Banks had long argued that because they had to hold required reserves, these reserves were a tax because the Fed did not pay interest on these holdings. Absent the requirement, banks could lend or invest those reserves to earn interest. As a result, banks maintained required reserves, but minimized excess reserves, preferring to earn interest by lending or investing the funds. And, because reserves were scarce, Banks frequently had to borrow in the federal funds market (paying the FFR) to ensure they were meeting their overnight reserve requirements.

In that framework, the Federal Reserve could raise or lower the FFR by making relatively small changes to the supply of reserves (see Figure 2 below). For example, the Fed could increase reserves by buying Treasury securities on the open market and crediting the accounts of the seller with reserves as payment. A greater quantity of reserves shifted the reserves supply curve to the right and put downward pressure on the FFR. And a lower FFR tended to put downward pressure on other interest rates in the economy.

Figure 2: Monetary Policy with Scarce Reserves

The supply of bank reserves is vertical because the supply of reserves collectively held by the banking system is determined by the Federal Reserve. (More precisely, a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve, determines a country’s "monetary base," which is the sum of currency held by the public plus total bank reserves. The monetary base equals the value of the central bank’s assets. But, conditional on the public’s choice of how much currency to hold, the choice of the monetary base pins down total bank reserves.)

When reserves are scarce, the Federal Reserve can shift the supply curve to the right or left by adding or subtracting reserves from the banking system using open market operations. The intersection of supply and demand determines the FFR.

When the supply curve was in the downward-sloping region of the demand curve, relatively small shifts in supply had a significant effect on the FFR. The Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York used open market operations to fine-tune the supply of reserves to achieve the target FFR set by the FOMC. This finetuning was done by selling or purchasing securities to shift the reserve supply curve left or right.

Likewise, the Fed could decrease reserves by selling Treasury securities on the open market and debiting the accounts of buyers. As the supply of reserves decreased, it shifted the reserves supply curve to the left and put upward pressure on the FFR. And as the FFR increased, so did other interest rates.

The Federal Reserve used these policies to achieve its dual mandate. For example, the Fed could increase reserves to decrease the FFR and other interest rates, thereby encouraging economic activity when the economy was in recession (to achieve its maximum employment objective). Or, it could reduce reserves to increase the FFR and other interest rates in an attempt to restrain spending when inflation exceeded its 2 percent inflation objective (to achieve its price stability objective). The Trading Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York conducted open market operations, as needed, to maintain the FFR very near the FOMC’s target rate (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Monetary Policy Prior to 2008 - The FFR Target

The FOMC’s FFR target has varied widely in response to economic conditions. Prior to 2008, the FOMC set a single target for the FFR and used open market operations to move the rate toward its target.

NOTE: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

SOURCE: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; accessed Feb. 22, 2019.

The Financial Crisis

The Financial Crisis and resulting recession, known as the Great Recession, hit the U.S. economy hard. By December 2008, the Federal Reserve had lowered the FFR to a target rate range of 0 to 25 basis points.4 Then, to provide further stimulus and liquidity, the Federal Reserve made a series of large-scale asset purchases between late 2008 and 2014.5 The primary purpose of these purchases was to lower long-term interest rates to encourage consumption and investment. The purchases, which were also open market operations, increased the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and also dramatically increased the amount of reserves in the banking system. In addition, over the course of the crisis, the Fed introduced two new tools to U.S. monetary policy: interest on reserves (IOR) and the overnight reverse repurchase agreement (ON RRP) facility. (See table below for a list of monetary policy acronyms.)

| Term | Acronym |

|---|---|

| Federal funds rate | FFR |

| Federal Open Market Committee | FOMC |

| Interest on reserves | IOR |

| Interest on required reserves | IORR |

| Interest on excess reserves | IOER |

| Overnight reverse repurchase agreement | ON RRP |

Congress had enacted IOR in 2006, with an originally scheduled start in 2011. To enable the Fed to use this tool during the Financial Crisis, the start was pushed up to October 2008, and it applied to both required reserves (paying interest on required reserves, or IORR) and excess reserves (paying interest on excess reserves, or IOER).6 IORR eliminates the implicit tax on reserves requirements. And, because the IOER rate influences banks’ decision to hold more or fewer reserves, it gives the Fed an additional tool for conducting monetary policy.7 Prior to the summer of 2008, excess reserves had not exceeded $2 billion; by December 2008 they reached $767 billion, eventually peaking near $2.7 trillion in August 2014 (see Figure 4 below) because of the large-scale asset purchases by the Fed over this period.

Figure 4: Excess Reserves (FRED Graph)

NOTE: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the NBER.

SOURCE: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; accessed Feb. 22, 2019.

The second new tool of monetary policy is the ON RRP facility: When an institution uses the ON RRP facility it essentially deposits reserves at the Fed overnight (with a U.S. government security from the Federal Reserve’s portfolio acting as collateral) and earns interest (the ON RRP rate) on the deposit.8 This is similar to a consumer buying a certificate of deposit, holding it for a specified time, and being paid interest when it is redeemed. The purpose of the ON RRP facility is to set a floor on interest rates.

The Current Framework: Monetary Policy with Ample Reserves

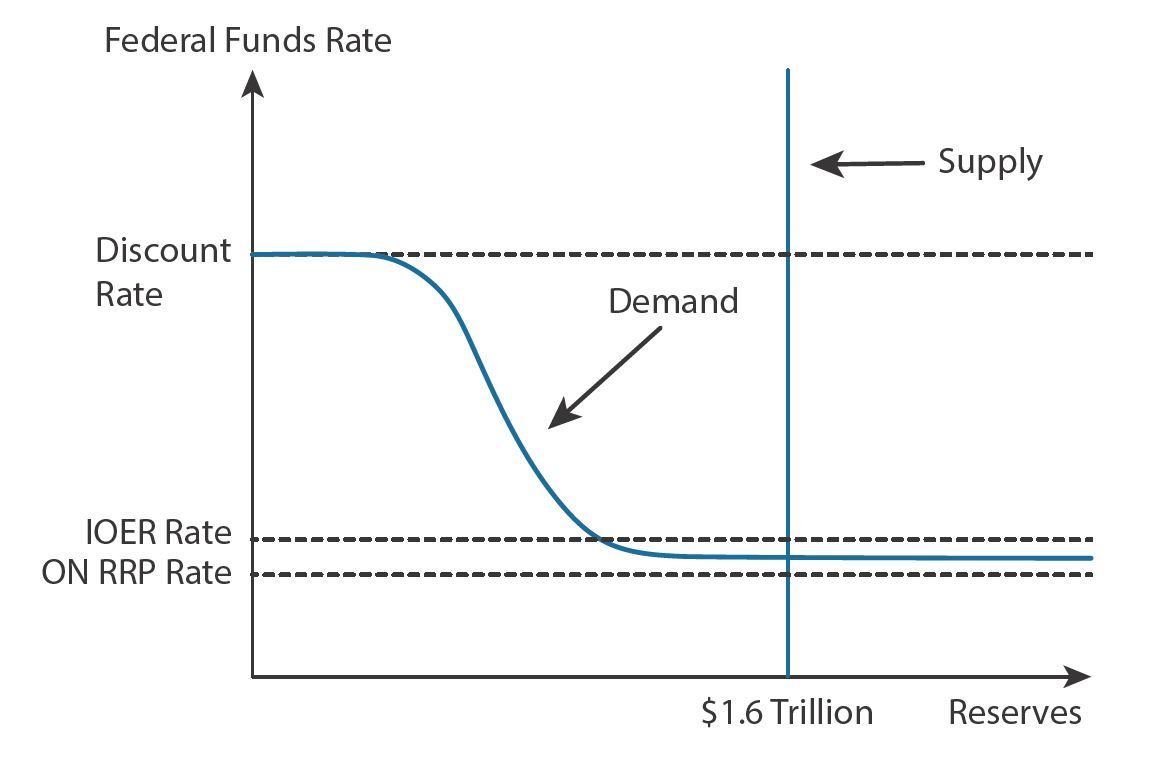

Although the quantity of excess reserves has been declining since its peak in 2014, reserve balances are currently far in excess of banks’ reserve requirements and the FOMC has indicated that it will in the longer-run conduct policy with ample reserves. With such a large quantity of reserves in the banking system, the Federal Reserve can no longer effectively influence the FFR by small changes in the supply of reserves. For example, a relatively small increase in reserves will not lower interest rates, nor will a relatively small reduction in reserves raise short-term interest rates (see Figure 5 below). Instead, the Fed uses its newer tools—IOER and the ON RRP facility—to influence the FRR and short-term interest rates more generally.

Figure 5: Monetary Policy with Ample Reserves

In a world with ample reserves, the Federal Reserve operates where the following are true:

-The demand curve is flat and near the IOER rate.

-The supply of reserves is ample and far to the right of the origin, intersecting demand on the flat portion of the curve. As such, making slight adjustments to the supply of reserves no longer puts upward or downward pressure on the FFR and instead the FFR is guided by the IOER rate as well as the ON RRP rate.

IOER

The IOER rate offers a safe, risk-free investment option to banks holding reserves at the Fed. Given this rate, banks will not lend reserves in the market for less than the IOER rate. Arbitrage plays a key role in steering the federal funds toward the target. For example, if the FFR falls very far below the IOER rate, banks have an incentive to borrow in the federal funds market and to deposit those reserves at the Fed, earning a profit on the difference. This tends to pull the FFR in the direction of the IOER rate (see Figure 6 below). As such, to conduct monetary policy, the Federal Reserve moves the FFR into the target range set by the FOMC primarily by adjusting the IOER rate.9 But not every financial institution can hold reserves with the Fed.

Figure 6: Interest on Excess Reserves (FRED Graph)

SOURCE: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; accessed Feb. 22, 2019.

ON RRP Facility

More types of financial institutions can participate in the ON RRP program than can earn interest on reserves. These institutions use the facility’s rate to arbitrage other short-term rates. In particular, because these institutions will never be willing to lend funds for lower than the ON RRP rate, the FFR will not fall below the ON RRP rate. As such, the rate paid on ON RRP transactions acts as a floor for the FFR.

FFR Range

Rather than setting a single target for the FFR, the target is now communicated as a range 25 basis points wide. As stated above, the IOER rate and ON RRP rate are used to guide the FFR within the target range (see Figure 7 below).

Figure 7: Monetary Policy with Ample Reserves (FRED Graph)

The FFR target is now communicated as a range 25 basis points wide rather than a single rate.

NOTE: Gray bar indicates recession as determined by the NBER.

SOURCE: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; accessed Feb. 22, 2019.

Despite the recent changes, the FFR will continue to be the primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy.10 And the transmission channels are the same—the FFR influences other interest rates in the economy, which influence the decisions of consumers and producers (see Figure 1 at the top). To conduct monetary policy, the FOMC increases or decreases the target range in a manner consistent with its policy goals of price stability and maximum employment.11

Conclusion

When reserves were scarce, the Federal Reserve could influence the FFR with small changes in the supply of reserves by conducting open market operations that would shift the supply curve to the right (increasing reserves) or left (decreasing reserves). In the past few years, the Federal Reserve has adopted a new strategy for implementing monetary policy. With ample reserves in the banking system, the Fed now sets a target range for the FFR and uses the rates on IOER and the ON RRP facility to keep the FFR rate in the FOMC’s target range.

Arbitrage: The simultaneous purchase and sale of a good in order to profit from a difference in price.

Balance sheet: A statement of the assets and liabilities of a firm or individual at some given time.

Federal funds rate (FFR): The interest rate at which a depository institution lends funds that are immediately available to another depository institution overnight.

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC): A committee created by law that consists of the seven members of the Board of Governors; the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; and, on a rotating basis, the presidents of four other Reserve Banks. Nonvoting Reserve Bank presidents also participate in FOMC deliberations and discussion.

Liquidity: The quality that makes an asset easily convertible into cash with relatively little loss of value in the conversion process.

Monetary policy: Central bank actions involving the use of interest rate or money supply tools to achieve such goals as maximum employment and stable prices.

Open market operations: The buying and selling of government securities through primary dealers by the Federal Reserve in order to influence the money supply.

Stimulus: Actions taken by a government or a central bank that are intended to encourage economic activity and growth.

- In 2008, as the FFR neared zero, the FOMC began to implement monetary policy primarily through purchases of long-term bonds to reduce long-term interest rates, a strategy commonly (but inaccurately) known as “quantitative easing.” Such purchases are one type of “unconventional” monetary policy. The FOMC supplemented this strategy with “forward guidance” to financial markets. The FFR remained near zero until December 2015.

- Short rates can differ because of several factors: the duration of the loan, the credit worthiness of the borrower, and whether collateral is required/available.

- Although legal reserve requirements still exist, in practice, financial innovation in the 1990s had enabled banks to avoid nearly any obligation to hold reserves.

- A basis point is 1/100th of 1 percent. It is used chiefly to express differences in interest rates. For example, an increase in a particular interest rate of 0.25 percent can be described as an increase of 25 basis points.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. “What Were the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchases?”

- Board of Governors. “Interest on Required Reserve Balances and Excess Balances.”

- Board of Governors. See footnote 6.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “Reverse Repo Counterparties.”

- Board of Governors. See footnote 6.

- Board of Governors. “FOMC Communications Related to Policy Normalization.”

- Board of Governors. See footnote 10.

Citation

Scott A. Wolla, ldquoA New Frontier: Monetary Policy with Ample Reserves,rdquo Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Page One Economics, May 3, 2019.

These essays from our education specialists cover economic and personal finance basics. Special versions are available for classroom use. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us