Robots: Helpers or Substitutes for Workers?

Technology is transformative, and with the rapid pace of change, workers might wonder: Are robots going to help me or take my job? Robots have already transformed industries from health care to manufacturing and have catalyzed important questions about the future of work. This blog post unpacks how economists examine this issue and recent research suggesting that, though the effects of automation are complex, some groups of workers will be disproportionately impacted.

In this blog post, we focused on robots that can interact with the physical world rather than artificial intelligence chatbots, like ChatGPT. Robots can be augmented by artificial intelligence, or AI, but they can also be designed to work based on classical computer engineering principles.

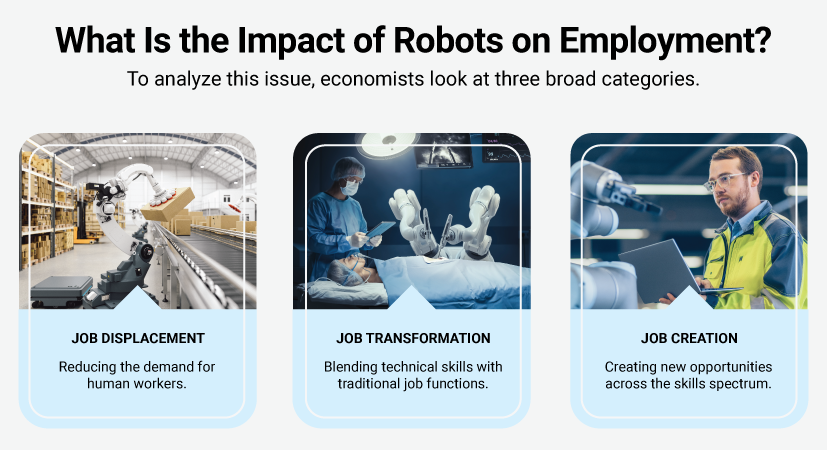

Robots can perform tasks that were once the sole domain of humans, leading to both opportunities and challenges in the labor market. Economists approach the question of robots’ impact on jobs by thinking about three broad categories: job displacement, job transformation and job creation. Here, we consider each potential effect of robots—and focus on how some groups, such as low-income workers with lower levels of education, are more profoundly affected. Finally, we address what some economists have already found about robots’ effects on employment.

How Automation Displaces Some Workers

Robots often outperform humans in efficiency and accuracy at routine tasks in highly controlled environments. Industrial robots are commonplace in manufacturing, handling tasks such as welding and packaging. Automotive factories use robots for assembling cars, reducing the need for human labor in those roles. And some other sectors, like mining, appear primed for more automation (PDF). Yet, while technological advances can lead to worker displacement, research has shown that growing trade deficits and taking production offshore have been bigger drivers of manufacturing job losses (PDF) in the U.S.

Today, robots are increasingly deployed in warehousing and logistics. Companies like Amazon and Walmart Inc. use robots for sorting, packing and moving goods. Automated guided vehicles (AGVs) and robotic arms streamline warehouse operations, which leads to a reduction in the demand for human warehouse workers.

Ways Robots Can Transform Jobs

Yet, while robots may eliminate some jobs, others may be transformed. The integration of robots often requires human oversight and maintenance, generating new roles that blend technical skills with traditional job functions.

Robots have the potential to complement many jobs in health care, assisting physical therapists with patients or surgeons in performing complex procedures. But even though robots may handle specific tasks, surgeons are needed to operate the robotic systems and interpret output data. Additionally, robots used for patient care and rehabilitation require health care professionals’ supervision.

In agriculture, drones can be used for crop monitoring and harvesting. Farmers’ skillsets now need to include expertise in managing these technologies, requiring a combination of agricultural knowledge with technical skills in robotics and data analysis.

How Robots Can Help with Job Creation

Robots may replace some jobs and transform others, but the increasing use of robots in a range of industries will also create new job opportunities across the skills spectrum.

On the one hand, jobs that have higher education requirements, such as those in designing, programming and manufacturing of robots, will mean more opportunities for engineers and technicians. Data collection and analysis are often needed to make sure that robots perform well, so jobs in data science, machine learning and artificial intelligence are poised to grow.

In addition, jobs that focus on the development, deployment and maintenance of robotic systems are likely to expand.

- Technicians and system operators will manage automated production lines.

- Drone operators will be responsible for the monitoring of processes, delivery services and infrastructure inspection.

- Logistics coordinators and quality control inspectors may manage the flow of goods even in largely automated warehouses, coordinating the movement of products and materials using robotic systems.

These occupations may require vocational or certificate training but could be available to workers without college degrees.

What Have Economists Found about Robots’ Effects on Workers?

Will robots replace workers or help them? Thus far, only a few studies have attempted to quantify the effects robots and automation have on employment and wages. Recent research suggests the balance between augmentation and replacement has not taken a decisive turn, but may be tipping gradually toward greater labor displacement (PDF).

The International Federation of Robotics has been measuring robot use since the late 1980s, which allows economists to measure how robot use affects job growth. In a 2019 report, economists William Rodgers III and Richard Freeman analyzed “How Robots Are Beginning to Affect Workers and Their Wages” by examining the U.S. labor market following the Great Recession, from 2009 to 2017. They found that throughout the post-recession recovery, there was both an increase in robot use and significant job growth in the U.S. labor market, suggesting the strong economy largely masked any job losses.

They also found that robot growth was not distributed equally across the nation. Instead, it was concentrated in the Midwestern states that make up the East North Central census division (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin) and in manufacturing industries. Nationwide, robot use grew from a little less than 0.8 robots per 1,000 workers in 2009 to 1.8 per 1,000 workers in 2017, and there was little evidence of job displacement. In the Midwest, some groups of workers even saw employment rates tick upwards. (Other research has confirmed that the productivity effect of automation (PDF) allows firms to increase production, lower prices and thus increase demand, which translates into higher employment in these businesses.)

In addition, Rodgers and Freeman found that employment effects of robots were highly specific to certain demographic groups and regions, with:

- A positive employment effect on young less-educated men and less-educated adult women nationwide, but a negative employment effect on young less-educated men and women in the Midwest manufacturing sector.“Young adults” are 16 to 24. “Adults” are 25 to 64.

- A positive impact on wages for young less-educated women and less-educated Black and Latino women and men nationwide, but a significant negative wage impact on young less-educated men and women in the Midwest manufacturing sector.

- The biggest negative wage effects on young less-educated Black men and women in Midwest manufacturing.

Rodgers and Freeman found some support for what economists call a productivity effect, when robot-produced efficiency gains create greater demand. Product prices fall, quality rises and wages increase, all enabling people to purchase more. To meet this growth in demand, employers may hire additional employees. However, they also found negative employment effects for lower-skilled Black workers, who already face lower wages and employment rates on average, suggesting these workers may be the first to be replaced.

Other studies have confirmed that robots and automation may have some positive employment effects, but have stronger negative wage effects, particularly for lower-skilled workers (PDF) who perform routine (and easy to automate) tasks and are on the lower end of the income spectrum. This means automation could contribute to rising wage inequality. Other researchers have found that because robots are capital-intensive, automation may also increase inequality through raising returns to wealth for the owners of the capital.

Economic and Social Considerations for Robot Impact

The impact of robots is not uniform across all workers. Low-skilled workers and individuals in lower-income brackets are more vulnerable to job displacement due to their higher representation in routine manual jobs that are more susceptible to automation (PDF). Older workers may also face greater challenges in adapting to new technologies due to disparities in access to training and education opportunities. In addition, negative effects on employment and wages seem to be the largest in manufacturing-heavy and robot-intense regions like the Midwest. Moreover, while robots may disrupt individual lives, the impact of technology extends beyond individual employment to broader economic and social considerations. While automation can lead to increased productivity and economic growth overall, it also raises concerns about rising income and wealth inequality.

Robots and automation technology are just beginning to reshape the job landscape. Although some jobs may be displaced, others may be transformed or created. Technology can raise living standards, boost productivity and help meet critical challenges, such as baby boomer retirements. But a balanced approach to automation considers both leveraging productivity benefits of robots and addressing the disproportionate effects they pose to some workers and their communities. By preparing for these changes, society can harness the benefits of automation while mitigating its challenges, ensuring a more inclusive and prosperous future for all workers.

Note

- “Young adults” are 16 to 24. “Adults” are 25 to 64.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us