When Does It Make Sense for Households to Borrow?

Why do people borrow? Student loans. Credit card debt. Mortgages. Payday loans.

News stories and public and policy discussions often center on these and other types of loans that many individuals and families take out. Most people will borrow money at some point in their lives, thus making lending a vital part of finance and the economy.

Borrowing often supports consumption, the largest component of gross domestic product, or GDP, a popular measure of economic activity. In total, as of the third quarter of 2023, the amount borrowed by U.S. households stood at about $17.29 trillion, about 63% of GDP.

Read on for a primer on the borrowing decision by individuals and families, including:

- An explanation of how the discipline of economics views the decision to borrow

- An example of “consumption smoothing”

- A look at how people buy “indivisible” goods

Then the post takes a look at why having access to affordable lending is important for economic equity.

What Are Common Rationales for Borrowing?

What does economic theory tell us about the circumstances in which it makes sense for a person or family to take out a loan?

Let’s begin with a few remarks about terminology.

When a person or family borrows money, we often describe this as “taking out a loan.” Alternatively, some people say they have “taken on debt” when they borrow. So the words “loan” and “debt” are synonymous (in some sense). Both relate to the act of borrowing.

From the standpoint of economic theory, two common rationales offered for borrowing are (a) “consumption smoothing” and (b) overcoming the fixed costs associated with “indivisible” goods. (Don’t worry about the lingo—more on this later.)

Consumption is the purchase of goods (e.g., a candy bar, gasoline or a TV) and services (e.g., a haircut, concert tickets or internet service). With the term consumption smoothing, economists are referring to the fact that people’s income often fluctuates over their lifetimes, but most people don’t want to experience large fluctuations in their consumption levels.

What’s an Example of Consumption Smoothing?

Consider the following simple example: Suppose “Arya” has a relatively low income of $1,500 per month today. However, she is in a training program offered by her employer and expects her future income to rise to $6,000 per month after she finishes the program. This would represent a quadrupling of her income over time.

Continuing with the example, let’s assume that Arya pays $1,200 in rent per month. If she expects her financial prospects to strengthen, she may want to move a bit of her future income to earlier in her life by borrowing some money now. She may not want to subsist on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches when she knows that in the future she’ll earn enough to cover her rent with over $4,800 to spare.

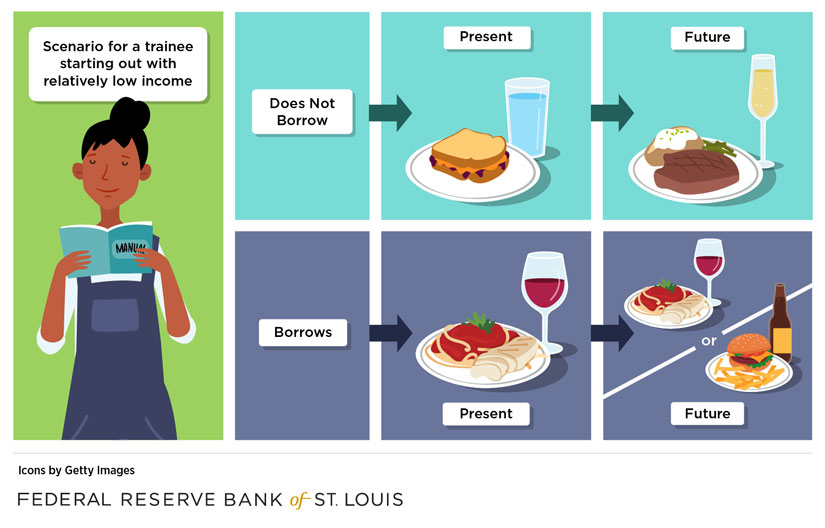

Arya could be viewed as having options like the two listed in the illustration below. Economists point out that it is logical for families to borrow in the “present” in such a situation. Households can smooth their consumption across time if they do.A more extreme example would be a situation in which a person’s income suddenly drops to zero. She might have borrow some funds in the short term to tide her over and then repay the money after she’s found a new job.

Food Choices with and without Consumption Smoothing

The point of this hypothetical (and somewhat whimsical) example is to show that a person can avoid fluctuating between two extremes if she chooses to borrow against her future income to adopt a consumption level that’s stable across time.

How Do People Buy “Indivisible” Goods?

When economists mention indivisible goods, they are referring to large purchases, such as of an education, car or home. A home will cost more money than a typical family earns in a year. Basic economic theory suggests this criterion shouldn’t necessarily be used to say the family can’t afford the home and shouldn’t purchase it. If the aspiring homeowners have steady jobs, they might be able borrow some funds to cover the cost of the house today and pay off the loan over time.

In this example, the home is an “indivisible” good. You can’t buy it room by room. Instead, you need to pay a large sum of money at the time of purchase to acquire it. Unless you have a lot of cash available, you will likely borrow and then pay off the loan little by little each month.In the U.S., it is standard for a prospective homebuyer to cover some of the home’s cost as a “down payment” at the time of purchase and borrow the rest.

A college education is another example of an “indivisible” good. Colleges charge tuition as students take classes instead of making students pay upfront for the four years that it typically takes to get a bachelor’s degree. But even a single semester of tuition can cost more money than many students or their families have on hand. In such a case, economic theory suggests that it is reasonable for students to borrow to pay for their college education. Empirical evidence indicates that, on average, people with a college degree earn more than people without a college degree. Accordingly, a college student might reasonably expect her income to rise after college, allowing her to repay her student loans after she graduates and is solely working. Investing in education thus provides another motivation for borrowing.

Access to Affordable Lending Is Important for Economic Equity

The St. Louis Fed’s Institute for Economic Equity works to support an economy where all can thrive. Given that borrowing money facilitates both consumption smoothing and the purchase of indivisible goods, it is an important part of economic equity and helping people thrive.

Moreover, families and individuals who cannot access mainstream financial services often suffer high costs and, in some cases, financial hardship, when they borrow. For example, borrowing for a home purchase via a “contract for deed” is an alternative to mainstream mortgage loans. This type of loan product can put borrowers at substantial risk (PDF) of losing their home, given that the contract often has a forfeiture clause which allows the lender to take back the property for a missed payment.

As a testament to how important the ability to borrow is, Congress in 1977 enacted the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) to ensure that low- to moderate-income (LMI) communities would have access to loans. In fact, the Federal Reserve System’s community development work was born out of the CRA and continues today. One purpose of the CRA is to decrease the likelihood that entire neighborhoods and subgroups of the population would be cut off from the ability to borrow, as occurred in the 20th century due to the practice of “redlining.” Making sure that everyone who is creditworthy can borrow on reasonable terms is crucial for economic equity.

Recap: The Role of Borrowing

To summarize, personal and family borrowing is a key part of people’s ability to control their financial lives. It allows people to draw on their financial resources over their lifetime. It also enables them to make big purchases and investments that they may not otherwise be able to do.

Importantly, the nation’s history shows the negative effects of inequities in access to credit. The recently issued final rule for CRA is one way in which the Fed continues to be responsive to the credit needs of communities, especially those in LMI neighborhoods.

Notes

- A more extreme example would be a situation in which a person’s income suddenly drops to zero. She might have to borrow some funds in the short term to tide her over and then repay the money after she’s found a new job.

- In the U.S., it is standard for a prospective homebuyer to cover some of the home’s cost as a “down payment” at the time of purchase and borrow the rest.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us