Which Students Were More Affected by Pandemic School Disruptions?

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, people made many adjustments in an effort to contain the spread of the virus. One such adjustment related to schooling.

A Review article published in January 2023 examined how education disruptions for school-aged children in U.S. households differed for various sociodemographic groups. The authors are Andrea Flores, who is an assistant professor at EPGE Brazilian School of Economics and Finance, and George-Levi Gayle, who is a research fellow at the St. Louis Fed and a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Flores and Gayle looked at learning format changes and access to computers for schoolwork for children from households of varying education levels, income levels, and races or ethnicities.

They found that children in households from disadvantaged sociodemographic groups were:

- More likely to have their classes canceled and less likely to switch to remote learning early in the pandemic

- Less likely to have access to computers for educational purposes, especially at the pandemic’s onset, and more likely to rely on schools to provide such resources

“Documenting the disparities observed in children’s ability to adjust to the different pandemic-related education disruptions is relevant since the disparities could translate into socio-demographic gaps in medium- and long-term education outcomes,” the authors wrote.

Data on Schooling Disruptions during the Pandemic

To study the disruptions in education that school-aged children in the U.S. faced and the students’ access to computers, Flores and Gayle used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. They were also able to obtain information on sociodemographic characteristics—e.g., household income, the level of education and race/ethnicity—of the respondents.

The authors’ analysis was based on data from April 23, 2020, through March 29, 2021, which included portions of two academic years.

“Thus, the data we use in our study allow us to capture the types of education disruptions experienced by children during two academic years and the extent to which schools were able to adjust to the social distancing measures adopted for the containment of the virus at the start of the 2020-21 academic year,” they wrote.

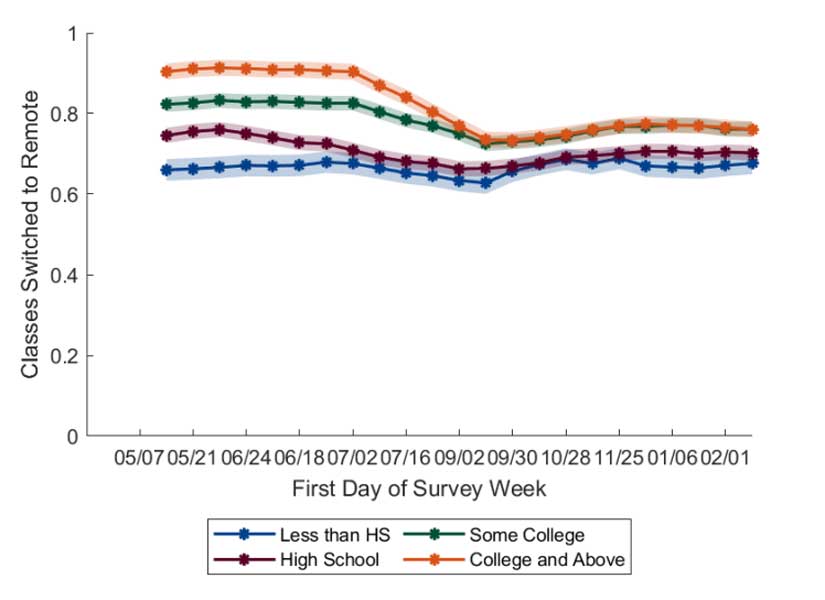

Likelihood of Switching to Remote Learning

Flores and Gayle found that, for the 2019-20 academic year, the likelihood of a switch to remote learning increased as the education of the survey respondents increased, as shown in the figure below. For instance, in 80% of households with schoolchildren where the respondent had a bachelor’s degree or higher, at least one child had shifted to remote learning, but that was the case in just over 60% of households where the respondent had less than a high school diploma.

Early Moves to Remote Learning Increased with Respondents’ Education

SOURCE: This figure is the left panel of Figure 1 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

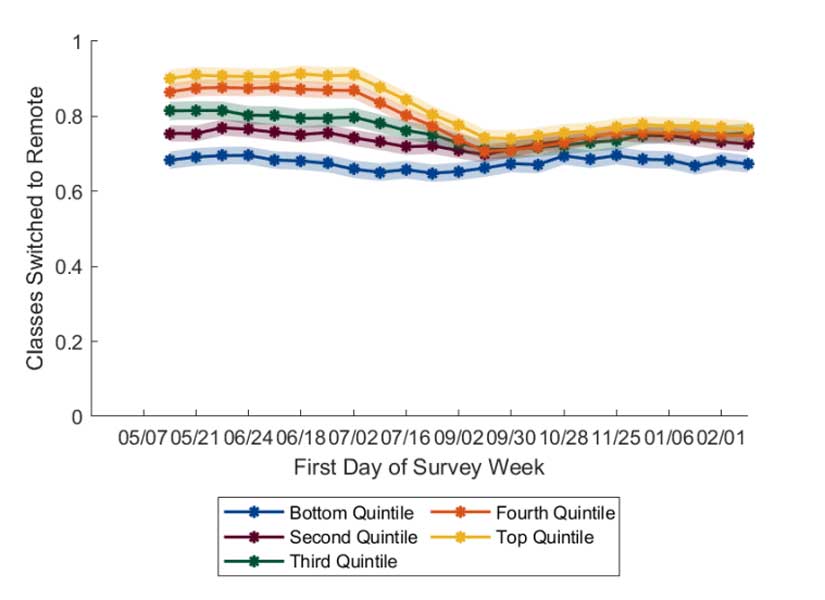

Similarly, the likelihood of switching to remote learning during the 2019-20 academic year increased as household income increased, the authors found. But during the 2020-21 academic year, the likelihood declined for higher-income households relative to the onset of the pandemic, as seen in the next figure.

Early Shifts to Remote Learning Rose with Household Income

SOURCE: This figure is the middle panel of Figure 1 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

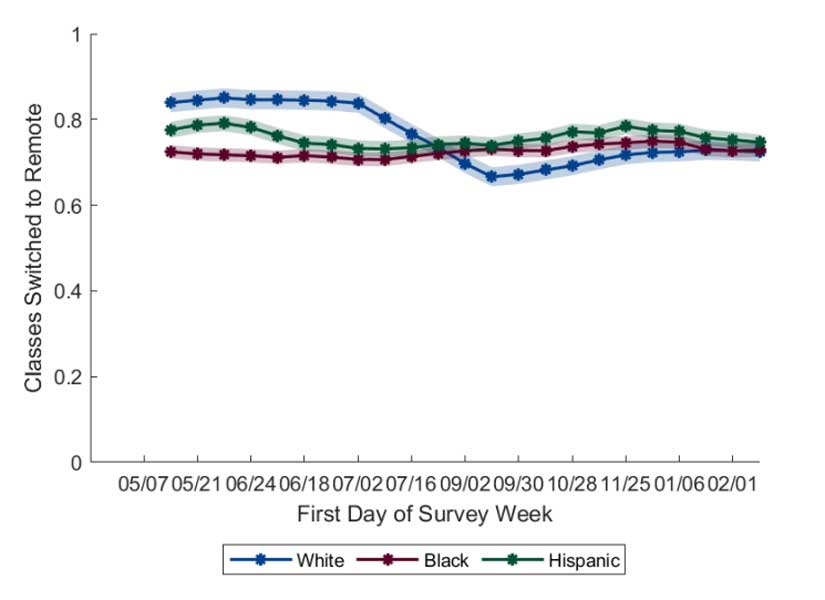

Flores and Gayle also found disparities in the switch to remote learning between households with white respondents and those with Black or Hispanic respondents. For the 2019-20 academic year, the fraction of white households that switched to remote learning was higher than the fraction of Black households and Hispanic households, as can be seen in the following figure. This gap reversed at the beginning of the 2020-21 academic year, as a higher percentage of white households than Black or Hispanic households reported in-person learning, the authors noted.

White Households Had Higher Rates of Early Moves to Remote Learning

SOURCE: This figure is the right panel of Figure 1 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

Regarding the suspension of classes at the beginning of the pandemic, the authors found that the percentage of households in which children had classes canceled decreased as the education of the respondent increased, meaning that those with less than a high school diploma had the highest likelihood of their children’s classes being canceled and those with at least a bachelor’s degree had the lowest likelihood. The authors also found that the likelihood of canceled classes decreased as household income increased. (See Figure 2 in the Review article by Flores and Gayle.)

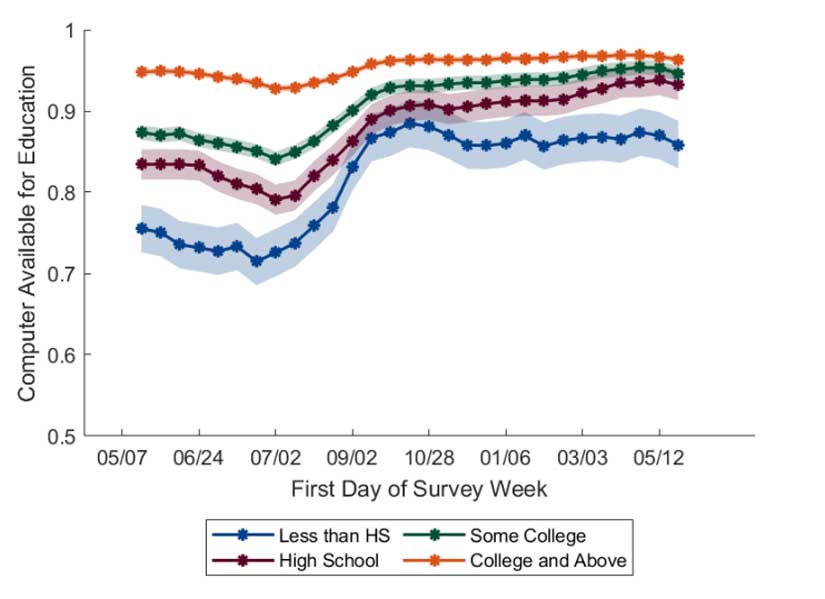

Likelihood of Having Access to a Computer for Schooling

Flores and Gayle also examined children’s access to computers for educational purposes as a way to examine students’ ability to adjust to the shift toward remote learning.

As shown in the next figure, such access increased with the respondents’ level of education. The authors found that, among households with children enrolled in school, more than 90% of those in which the respondent had at least a bachelor’s degree had a computer available for schooling. In contrast, less than 76% of those in which the respondent had less than a high school diploma reported having this resource available between May and July 2020. The gap decreased at the start of the 2020-21 academic year, largely because of an increase in support from schools in providing access to a computer, the authors noted.

Computer Access Rose with Respondents’ Education

SOURCE: This figure is the left panel of Figure 4 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

Similarly, the authors found that the percentage having access to a computer for educational purposes increased with household income, as the following figure shows. Again, the gap in computer availability decreased at the start of the 2020-21 academic year as more households gained access to a computer for education, suggesting more support from schools.

Computer Access Increased with Household Income

SOURCE: This figure is the middle panel of Figure 4 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

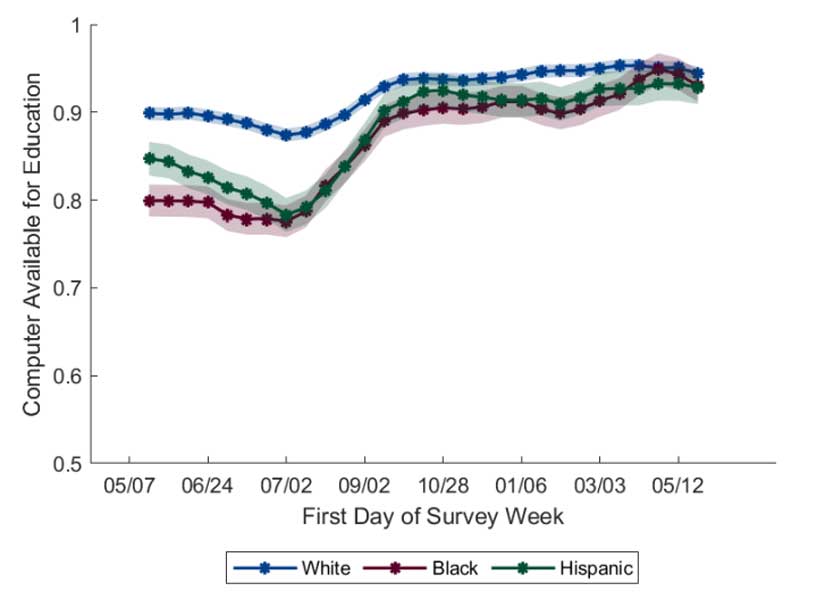

The authors also found that a higher share of white respondents’ households than Black or Hispanic respondents’ households had computer access for educational purposes. In addition, they found that Black and Hispanic respondents’ households relied more on schools for access to a computer. (See Figures 5 and 6 in their Review article for details on the fraction of households with computer availability provided by the child’s school or by someone in the household or family.)

Higher Percentage of White Households Had Computer Access

SOURCE: This figure is the right panel of Figure 4 in the January 2023 Review article by Andrea Flores and George-Levi Gayle, “The Unequal Responses to Pandemic-Induced Schooling Shocks.”

The authors noted that the disparities in learning format and in computer access during the first two school years that were affected by the pandemic “jeopardized the equalizing role of schools” for students from disadvantaged sociodemographic groups.

“Nonetheless, despite a weakening of the equalizing role of schools, schools still play an essential role in providing access to necessary learning resources to help students from disadvantaged groups—particularly those hit harder by employment income losses—adapt to the education disruptions experienced during the pandemic,” the authors wrote.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us