Step Back in Time and into Ordinary Workers’ Shoes

The St. Louis Fed’s online digital library FRASER is known for its large collections of statistical releases and archival materials related to Fed history.

But it also tells stories, as Senior Digital Projects Librarian Jona Whipple said in a FRASER newsletter early this year. She pointed out resources that give perspectives into the conditions and struggles of ordinary workers at different moments in the 20th century.

Here are a few highlights. Step back in time and take a look:

- It’s a little more than 100 years ago, and you’re a young woman working in New York. Where are you living?

- Skipping forward a few decades: You’re a soldier returning from the front line at the end of World War II. What is the job market like? How have prices changed?

- Or put yourself in the shoes of a Black American in 1939. The New York World’s Fair is showcasing an awe-inspiring vision of the future, but where in the fair organization can you work?

“The cramped and awful loneliness of a hall bedroom”

The Metropolitan Board of the Young Woman’s Christian Association in 1915 studied whether to build more boarding homes or hotels with subsidized room and board for “self-supporting women.” The resulting report, described in the May 1916 Monthly Labor Review by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), gave a peek into where single working women of New York were living.

The YWCA researchers personally spoke to or saw nearly 700 women. Of those, most were living in subsidized homes or renting rooms in boarding houses or from families. Only 37 were in their own private apartments.

Living alongside strangers in boarding houses or with families in private homes could be risky, and one of the questions the YWCA board asked was why more young women didn’t take advantage of the subsidized homes. Perceived restrictions were one of the main reasons given.

“I don’t know which is worse,” the report quoted one woman as saying, “the cramped and awful loneliness of a hall bedroom or the humiliating and soul-depressing charity and rules of a home.”

Those living in their own private apartments and cooking for themselves, meanwhile, said they wouldn’t want another arrangement, and were spending amounts that favorably compared with the amounts paid for room and board—paying rent “as low as $2.25 a week” and $2 to $2.50 a week for groceries.

“The ranks of discharged war workers will be considerably swelled”

What was it like for a soldier coming home from World War II and searching for a civilian job? Soldiers experienced tectonic shifts in the employment landscape and faced price increases, according to BLS reports.

Over a year before the war officially ended, the tremors were being felt in employment. U.S. war veterans already were seeking jobs, and so were workers from plants that were scaling back or winding down war efforts, Massachusetts statistician Verna Fine wrote in a report in the October 1944 Monthly Labor Review. She noted, however, that in many areas there was a labor shortage.

“As of December 1943, of the 430,000 Massachusetts citizens who entered the armed forces, already over 60,000 have been returned to civilian life,” Fine wrote. “Before final victory, there will certainly be an increase in the number of discharged veterans; and, with major cut-backs and cancellations, the ranks of discharged war workers will be considerably swelled.”

A shopper and her son in 1944 weigh posted price and point values in purchasing canned foods under a war ration book. Food led consumer price increases between 1939 and 1944, according to a 1946 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics report.

Photo via Farm Security Administration–Office of War Information Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress.

Consumer prices, meanwhile, had been rising, particularly for food, which saw a 43% increase between 1939 and 1944, according to a 1946 BLS bulletin.

1939: Growing discrimination is “a matter of serious concern”

The job market, of course, wasn’t the same for everyone: A person’s race could curtail opportunities, as a 1939 report from a New York State commission documented. Growing discrimination against Black workers in “any but manual and unskilled jobs is a matter of serious concern,” according to a report in the August 1939 Monthly Labor Review issue.

(The publication used terms for Black Americans that were in more common use at the time. FRASER notes that original descriptions are retained to ensure that they are not erased from the historical record, but that discriminatory or biased language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups is inconsistent with the values of the Federal Reserve.)

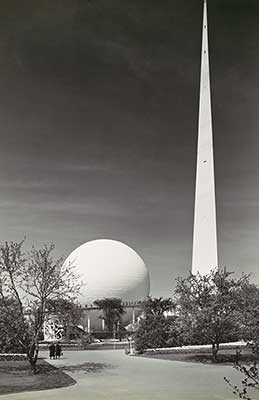

The Trylon and Perisphere at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Despite large amounts of state funding for the fair, only 65 Black workers were able to get some of the 1,900 administrative and construction jobs, a New York commission found.

Photo by Samuel H. Gottscho via Wikimedia Commons.

Among a litany of discriminatory practices, the commission found:

- “Financial and mercantile enterprises” employing hundreds of thousands of white-collar workers throughout the state didn’t hire Black workers for those occupations.

- Except for clothing and related industries in New York City, the state’s factories for the most part afforded no openings for Black workers.

- Only about 65 Black workers, mainly in “menial” positions, held some of the 1,900 New York World’s Fair administrative and construction jobs, an inequitable share “especially in view of the fact that over 70 million dollars of New York City’s public moneys have been invested in the fair,” the commission said.

Some campaigns, including threatened boycotts, enabled Black workers to get jobs in offices and stores, most notably in the Harlem section of New York, where several hundred Black residents were hired as clerks in 1934 and 1935.

“In general, however, the concessions [after campaigns] have been temporary and have involved only a few new employment opportunities,” the review article noted.

The civil rights and other movements in the decades to come added more to the story, of course. As FRASER’s Whipple noted, zooming out on the timeline “tells a longer, ongoing story of race and its effects on work, wages and economic progress.”

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us