How Hamilton Laid the Foundation for the Fed

“The ten-dollar founding father without a father got a lot farther by working a lot harder, by being a lot smarter, by being a self-starter. By fourteen, they placed him in charge of a trading charter.”

A character sings this line near the beginning of the first song in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical, “Hamilton.”

Alexander Hamilton exemplifies the rags-to-riches story. He came from a poor family in the Caribbean, but held the title of the first Secretary of the U.S. Treasury a few years after turning 30. This man appears on the $10 bill—and has a Tony award-winning musical named after him (now on streaming service Disney+).

Clearly, that’s an impressive legacy.

The musical highlights many of Hamilton’s achievements, and one of these includes crafting the nation’s original central bank, known as the First Bank of the United States.

Act 1

Scene 1 — The Beginning

After the Revolutionary War, presidential electors chose George Washington to serve as the leader of the new United States. In office, Washington created the Cabinet, and in September 1789, he appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first Treasury secretary.

Hamilton had a daunting task in front of him. America was still recovering from its fight against Britain. The nation had substantial debt, a significant portion of which was issued by individual states.

Also, to finance the war, the Continental Congress had issued currency that severe inflation had rendered almost worthless. The notes, known as “continentals,” were backed by the anticipation of tax revenues and were easily counterfeited.

Scene 2 — The Plan to Become a Financial Powerhouse

As Treasury secretary, Hamilton had plans to foster a powerful national economy that could compete on a global scale.

He believed that a strong and stable national currency was needed to make this happen, and that the federal government should consolidate the states’ war debts. So, Hamilton strived to establish the U.S. Mint. He proposed a whiskey tax to generate revenue to help fund government expenses and pay off debt.

Hamilton also looked toward central banks in Europe. He believed that having a central bank in America would foster a strong financial system.

Act 2

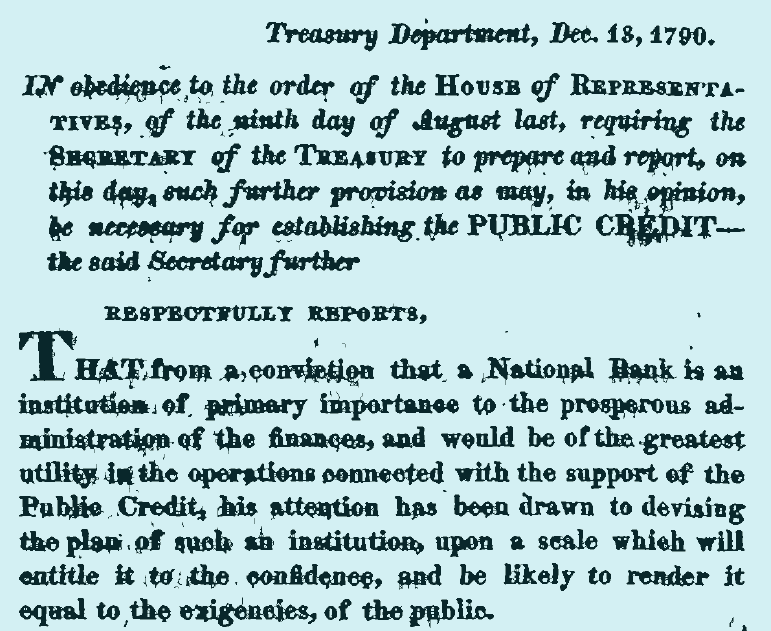

This is the introduction to Hamilton’s “Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the Subject of a National Bank,” read in the House of Representatives, dating from Dec. 13, 1790. You can read the full document in our digital library, FRASER.

Scene 3 — The Process

Hamilton encountered resistance when he proposed his plan for a U.S. central bank to Congress in December 1790.

Notably, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison opposed a central banking system, which they said was unconstitutional. The 10th Amendment says that powers not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution rest in the hands of the states. And thus the constitutional powers over the creation of a central bank rested at the state level rather than the federal level, they argued.Hamilton believed that the “necessary and proper” clause in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution justified his plan. This clause gives Congress implied powers. So, if Congress thinks an action is necessary to help meet the nation’s needs, Congress has the power to pass a bill to take that action.

Geographical divisions also led to disagreement over the creation of a central banking system. People who were part of the agrarian culture in the South favored a smaller and less powerful institution. Some residents of the North, which had trading and manufacturing at its center, believed the nation would benefit from a national bank.

Hamilton was persistent, and in early 1791, Congress passed the bill that created the nation’s first central banking system. After Hamilton presented his case in a 15,000-word essay, “On the Constitutionality of a National Bank,” President Washington signed the bill into law on Feb. 25, 1791.

Stage Directions: Enter First Bank of the United States.

Scene 4 — The Bank

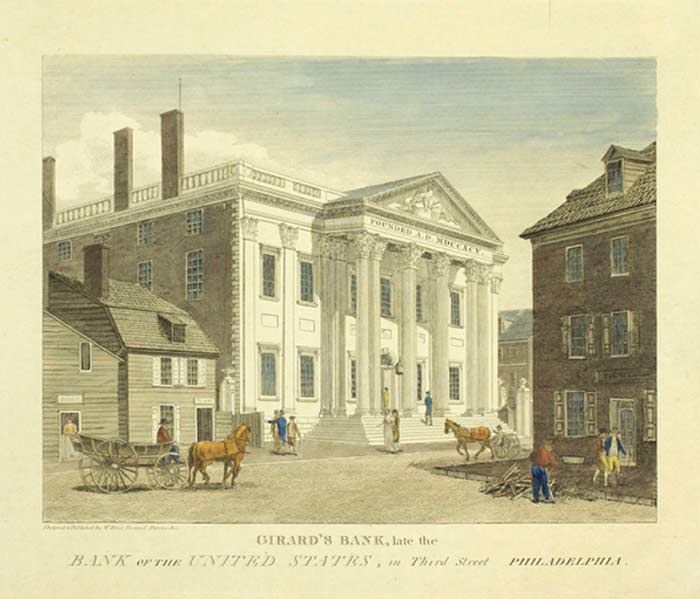

The First Bank of the United States, headquartered in Philadelphia, had startup capital of $10 million, which is equivalent to approximately $280 million in today’s dollars. The U.S. government held 20% of the capital, and thus became a minority stockholder in the bank. Private investors held the remaining $8 million.

In 1792, branches were established in four cities—Boston, New York, Baltimore and Charleston, S.C.—to help the bank facilitate the flow of money and credit around the country. Four additional branches were added in Norfolk, Va.; Savannah, Ga.; Washington, D.C.; and New Orleans.

The First Bank acted as the federal government’s fiscal agent, collecting taxes and paying the government’s bills. It also accepted deposits, made loans and distributed and helped circulate currency. With its acceptance of deposits and issuing of loans, the national bank also acted as a commercial bank, and helped more businesses and citizens across the country get access to capital.

Overall, the First Bank’s actions were intended to help the nation recover from its post-war problems and establish a healthy economy.

Scene 5 — The End. But Not Really ...

Alexander Hamilton didn't just lend his name to the hit Broadway musical; he was the voice behind the idea of central banking in the United States. Step back into the late 1700s in this video from the Dallas Fed.

When Congress passed Hamilton’s bill for a central bank, the First Bank received a 20-year charter. When the charter expired in 1811, Congress did not renew it.

Hamilton had died in a duel with Aaron Burr seven years earlier (1804), so he could not argue for the renewal. In addition, there were still opponents of the First Bank who considered it unconstitutional. The bank closed on March 3, 1811.

However, the central banking system Hamilton created lived on. His work laid the foundation for central banking in the United States, and many aspects of the First Bank are noticeable in today’s central banking system, the Federal Reserve.

For example, the Fed’s structure ensures political independence, and the system is considered “independent within the government.” The First Bank also had a quasi-governmental structure, as the government was a minority stakeholder while private investors held spots on the board of directors.

The Federal Reserve serves as the fiscal agent for the U.S. Treasury, a responsibility that the First Bank also had.

However, an important difference between the two central banking systems is that the Fed does not act as a commercial bank for the American people. Instead, the Fed acts as a bank for commercial banks. Regional Reserve banks are often described as “bankers’ banks.”

Curtain Call

Hamilton’s hard work more than two centuries ago paved the way for a sound financial system in the United States.

Not only is there an award-winning musical that bears his name and a $10 bill with his image, but there is also a central banking system for which he laid the foundation.

*Applause*

Retrieved from Federal Reserve History: The First Bank of the United States (Library Company of Philadelphia (www.librarycompany.org) Print Dept. Birch's views [Sn 17a/P.2276.38])

The St. Louis Fed’s digital library, FRASER, is full of history. Discover more about the First Bank of the United States, and check out Hamilton’s works, including his 1790 report to the House of Representatives on the subject of a national bank.

You can also dig into the founding of the Federal Reserve System in this blog series.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us