Do Longer Lives and Fewer Babies Affect the Natural Interest Rate?

What could be driving a long-run decline in the natural rate of interest?

That’s a question St. Louis Fed Economist Sungki Hong and Senior Research Associate Hannah Shell explored in a 2019 essay, Factors Behind the Decline in the U.S. Natural Rate of Interest. They concluded that, most likely, changing U.S. demographics are contributing factors.

By changing demographics, the authors mean that Americans are living longer and having fewer babies.

This blog post will explore how that relationship works. But first, let’s get our heads around the natural rate of interest is and why it matters.

Understanding the Natural Rate of Interest

As Hong and Shell explained in another recent essay, the natural rate of interest is the real short-term rate that occurs when the economy has reached maximum employment and has stable inflation. In other words, it’s the prevailing interest rate when the economy is in equilibrium; monetary policy is neither accommodative (i.e., a central bank isn’t trying to spur economic growth) nor restrictive (i.e., a central bank isn’t trying to temper inflation).

The natural rate of interest also is known as the neutral rate, r-star or r*. As economic terms go, it’s a fun one to know.

How do you determine the natural rate of interest?

You’ll notice that Hong and Shell used the word “real” in their writings. In economics, real means adjusted for expected inflation (versus nominal, which means not inflation adjusted). That’s important to clarify, because the natural rate of interest isn’t “real” in the sense you might think. It’s an inferred rate that cannot be directly observed—only estimated.

Hong and Shell explain that to uncover the underlying natural rate of interest, experts use quantitative macroeconomic models that describe the policy and economic activity of the government, households and businesses.

OK … why do people work so hard to estimate it?

The authors explain that the rate matters to the Federal Reserve because it’s an “essential benchmark” for the policy rate target the Fed sets, which then ripples out to consumer interest rates such as car loans and mortgages. Financial markets are likewise interested in the natural rate due to the close relationship between the Fed’s policy rate and yields on short-term government and private bonds.

What does the natural rate of interest look like?

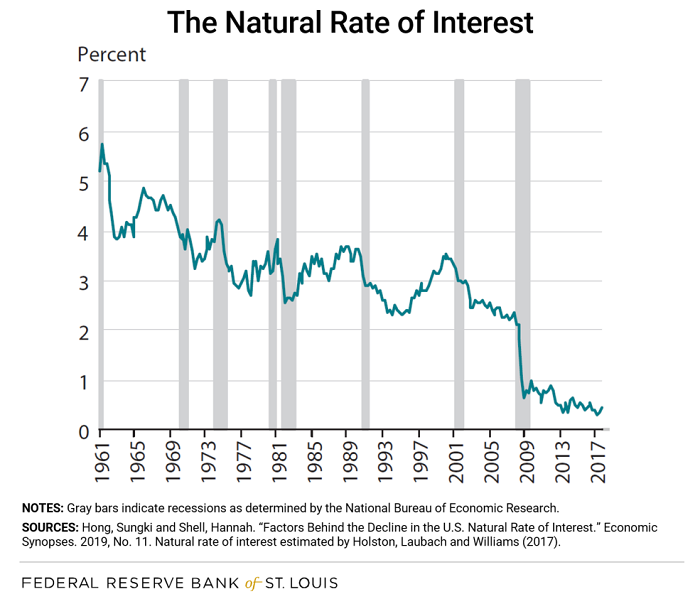

Here's how the U.S. natural rate of interest has trended over time, as presented by Hong and Shell. Their figure plotted the rate as estimated by New York Fed President John Williams and co-authors Kathryn Holston and Thomas Laubach of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.Holston, Kathryn; Laubach, Thomas and Williams, John C. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants.” Journal of International Economics, 2017, 108, pp. S59-S75.

Hong and Shell noted that the rate started at slightly below 6% in the early 1960s. It generally increased during economic expansions and decreased during recessions.

But during the Great Recession, the rate dropped quickly and did not increase during the ensuing expansion. Why not?

Factoring in Changing U.S. Demographics

To help explain this long-term decline in the natural rate of interest, the authors looked at shifting U.S. demographics. They examined three measures:

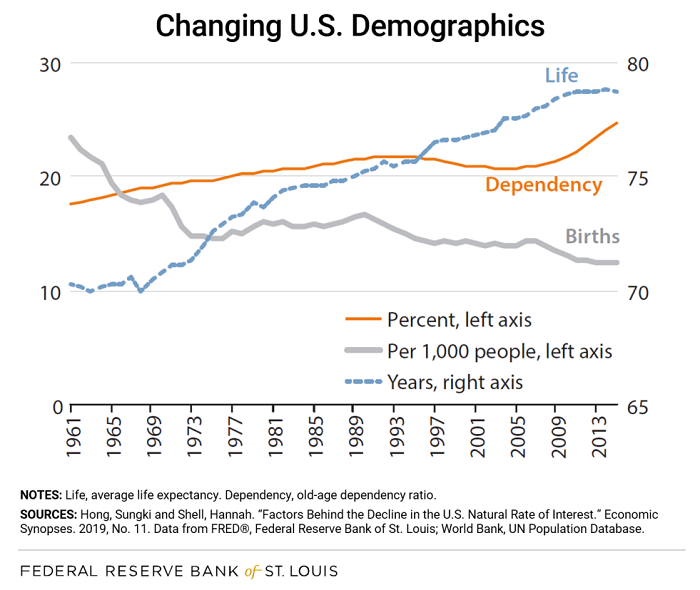

- Average life expectancy at birth (blue line)

- The birth rate per 1,000 people (gray line)

- The old-age dependency ratio (orange line)

As seen in their figure below, average life expectancy has increased over time, while the birth rate has dropped from about 23 births per 1,000 in 1961 to about a dozen per 1,000 in 2015.

We have an aging population: People in the U.S. are living longer, while population growth is slowing.

Check out the third measure: the old-age dependency ratio. This is calculated by dividing the population older than 65 by the population between 20 and 65 years old. The old-age dependency ratio has increased in the U.S. since the 1960s. The authors said this is putting a bigger burden on working-age adults to support retirees through payments such as Social Security.

To dig into how these demographic changes can affect the natural rate of interest, Hong and Shell considered related measures: U.S. labor force participation and the household savings rate. They concluded that, most likely, changing U.S. demographics are reducing the natural rate of interest by decreasing potential output.

Potential output is the amount of goods and services that an economy can produce when it fully employs its available resources. If potential output declines, Hong and Shell said, the natural rate of interest declines with it.

“An aging population and slowing population growth limit the supply of available workers in an economy,” Hong and Shell wrote. “Therefore, holding labor productivity constant, a decrease in workers—a higher old-age dependency ratio—reduces the output generated by an economy.”

They continued: “A smaller working-age population means fewer people with a lot of disposable income to consume. These factors decrease an economy’s productive capacity and thereby lower the natural rate.”

So, the thinking goes, Americans are living longer and having fewer children … which means more retirees and fewer workers … which means lower potential output … which means a lower natural rate of interest.

Notes and References

1 Holston, Kathryn; Laubach, Thomas and Williams, John C. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants.” Journal of International Economics, 2017, 108, pp. S59-S75.

Additional Resources

For more on the topics mentioned in this post, check out:

- From the President: Bullard on R-Star: The Natural Real Rate of Interest

- Open Vault: How Does the Federal Funds Rate Affect Consumers?

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us