The Recent Surge in Immigration and Its Impact on Unemployment

Recent U.S. immigration trends have sparked debate, not only about the potential social and economic effects but also about whether official statistics accurately capture the scale of recent arrivals. Policymakers and researchers often rely on sources like the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) to gauge the impact of immigration on the labor market. Yet data from other sources show U.S. immigration levels that are higher than the CPS estimates.

For example, the CPS estimated the net increase in the immigrant population was 3.94 million people from January 2022 to October 2024. However, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which uses additional data sources, estimated the net increase was more than twice the CPS estimate over the same period, for a total of 8.65 million people.The net change reflects new immigrants entering the U.S. less immigrant deaths and immigrants leaving the country. For the CBO estimate, I prorated the CBO projection for full-year 2024, which can be found in “The Demographic Outlook: 2024 to 2054,” January 2024. This discrepancy raises questions about the completeness and accuracy of recent CPS data.

Since official unemployment statistics are based on CPS data, some observers have expressed concern that an undercount of recent immigrants in the CPS may lead to a significant gap between reported unemployment rates and true labor market conditions. For example, if unemployed immigrants were undercounted by a large degree, the actual demand for labor might be weaker than what the official unemployment rate indicates.

This blog post suggests that such concerns are unwarranted. While recent immigrants tend to have higher unemployment rates, as a group their small share of the labor force limits the effect on overall unemployment figures, even when accounting for those not fully captured in the CPS.

Measuring the Unemployment Rate

The official U.S. unemployment rate is derived from the CPS, which is conducted monthly as a sample survey of about 60,000 American households. The employment status of each household member ages 16 and older is classified as employed, unemployed or not in the labor force based on answers to a series of questions. Individuals are considered unemployed if they actively searched for a job during the four weeks ending with the reference week. The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed individuals by the labor force, defined as the sum of employed and unemployed individuals.

Measuring Immigration Status in the Current Population Survey

In the CPS, respondents are asked about their citizenship status and when they immigrated. The CPS, however, doesn’t provide the respondents’ exact year of entry; instead, the entry is given within a range of years. In even survey years (as in 2024), “recent immigrants” are defined as those who reported immigrating in that year or the previous two calendar years. In odd survey years, recent immigrants are defined as those who reported immigrating in that survey year or the previous three calendar years.

Taking this data, I’ve divided the immigrant population into recent immigrants and non-recent immigrants. This allows us to analyze how immigration timing may affect labor market outcomes.

Labor Market Outcomes by Immigration Status

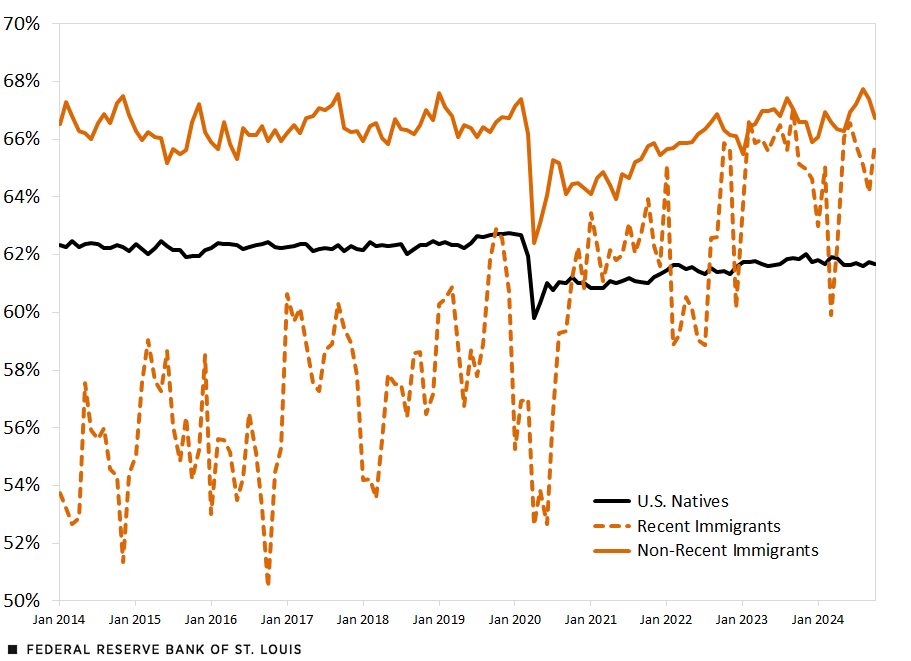

The figure below shows labor force participation (LFP) rates for U.S. natives (those born in the U.S. or abroad to U.S. citizen parents), recent immigrants and non-recent immigrants since 2014. The LFP rate for non-recent immigrants is typically higher than that for U.S. natives. Recent immigrants initially had the lowest LFP rate, but this rate has increased significantly over time; it now exceeds the rate for U.S. natives and remains slightly below the rate for non-recent immigrants.

Labor Force Participation Rate by Immigration Status

SOURCES: IPUMS and author’s calculations.

NOTES: Sample size includes ages 16 and older. Rates are seasonally adjusted. In surveys conducted in even years by the CPS, “recent immigrants” are defined as those who reported immigrating in that year or the previous two calendar years; in odd survey years, recent immigrants are defined as those who reported immigrating in the survey year or the previous three calendar years. The figure’s data are available for download.

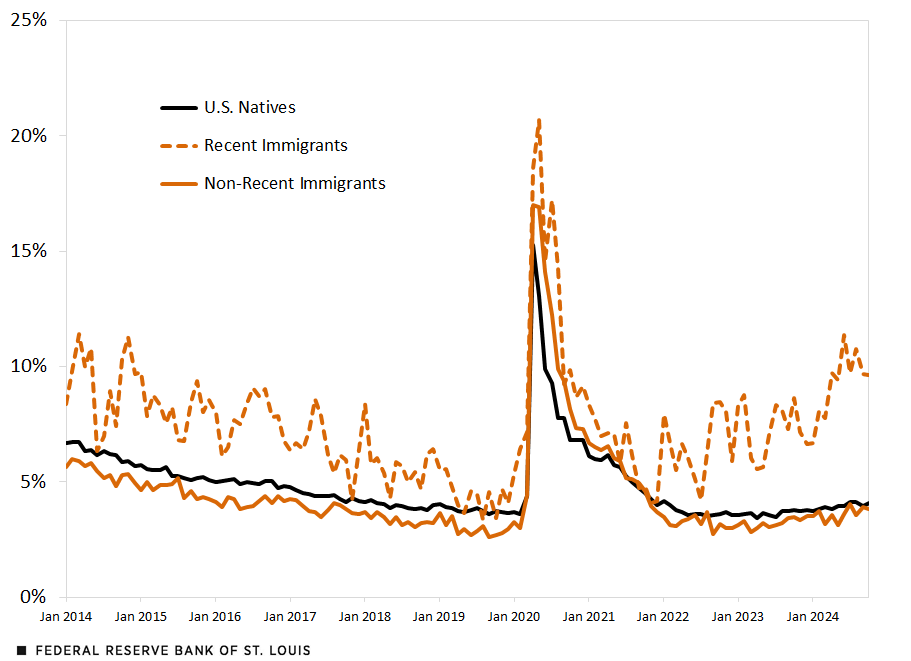

The next figure illustrates unemployment rates by immigration status since 2014. Except for a period following the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, non-recent immigrants generally experienced lower unemployment than U.S. natives, while recent immigrants consistently faced the highest unemployment rates among the three groups. Since 2022, the average unemployment rate for recent immigrants has been around 7.6%, compared with 3.8% for U.S. natives and 3.3% for non-recent immigrants.

Unemployment Rate by Immigration Status

SOURCES: IPUMS and author’s calculations.

NOTES: Sample size includes ages 16 and older, employed and unemployed. Rates are seasonally adjusted. In surveys conducted in even years by the CPS, “recent immigrants” are defined as those who reported immigrating in that year or the previous two calendar years; in odd survey years, recent immigrants are defined as those who reported immigrating in the survey year or the previous three calendar years. The figure’s data are available for download.

The Recent Surge in Immigration and Its Impact on the Unemployment Rate

Given the higher unemployment rates of recent immigrants and the recent surge in immigration, a natural question is: What effect does this have on the overall unemployment rate? To answer this question, we first need to understand the magnitude of the recent immigration surge captured by the CPS.

As of October 2024, the CPS recorded 4.91 million people who had immigrated to the U.S. since January 2022 and were still residing in the country. Coupled with a rising labor force participation rate among recent immigrants, this influx tripled this group’s share in the U.S. labor force, from 0.6% in January 2022 to 1.9% in October 2024.

However, it is well known that recent immigrants are often undercounted in the CPS due to factors such as a reluctance to participate in surveys, especially among those without legal status; language barriers; and limitations of the CPS’ sampling framework.

To examine the potential impact of this undercount, I calculated an alternative unemployment rate. This rate assumes (1) immigration followed the CBO’s growth trajectory, and (2) the “missing” recent immigrants had the same labor force participation and unemployment rates as those included in the CPS.In this exercise, I took the difference between the CPS’ net change in immigration and the CBO’s net change in immigration and then added it to 4.91 million. This provides an approximate upper bound for the number of recent immigrants.

In January 2022, recent immigrants accounted for 0.6% of the labor force according to CPS data; in October 2024, this share was 1.9%. Including the undercounted recent immigrants, this share would have been 3.7% in October 2024.

The official unemployment rate in October 2024 was 4.14%. Factoring in the missing recent immigrants would raise this rate by a modest 0.10 percentage points, to 4.24%. Another way to analyze the effect is by comparing the actual unemployment rate with the rate excluding all recent immigrants estimated by CPS. Excluding all recent immigrants, the October 2024 unemployment rate would stand at 4.04% instead of 4.14%.

Summary

From a statistical standpoint, the impact of recent immigration on the unemployment rate is minimal. This is largely because the share of recent immigrants in both the population and labor force remains small, even with the recent surge.

However, this analysis does not capture the potential impacts that recent immigrants might have on the unemployment rate of incumbent workers—those already in the country—who may compete for similar jobs. For instance, the unemployment rate excluding recent immigrants could potentially have been slightly lower than 4.04% in the absence of the recent surge in immigration. Nevertheless, empirical research suggests that even for the most affected incumbents, the effects are very small at best and are negligible for the aggregate unemployment rate, given the small share of affected workers.For example, see Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov’s 2019 article, “The Labor Market Effects of a Refugee Wave Synthetic Control Method Meets the Mariel Boatlift,” in the Journal of Human Resources.

Notes

- The net change reflects new immigrants entering the U.S. less immigrant deaths and immigrants leaving the country. For the CBO estimate, I prorated the CBO projection for full-year 2024, which can be found in “The Demographic Outlook: 2024 to 2054,” January 2024.

- In this exercise, I took the difference between the CPS’ net change in immigration and the CBO’s net change in immigration and then added it to 4.91 million. This provides an approximate upper bound for the number of recent immigrants.

- For example, see Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov’s 2019 article, “The Labor Market Effects of a Refugee Wave Synthetic Control Method Meets the Mariel Boatlift,” in the Journal of Human Resources.

Citation

Alexander Bick, ldquoThe Recent Surge in Immigration and Its Impact on Unemployment,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 3, 2025.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions