The Impact of Work from Home on Interstate Migration in the U.S.

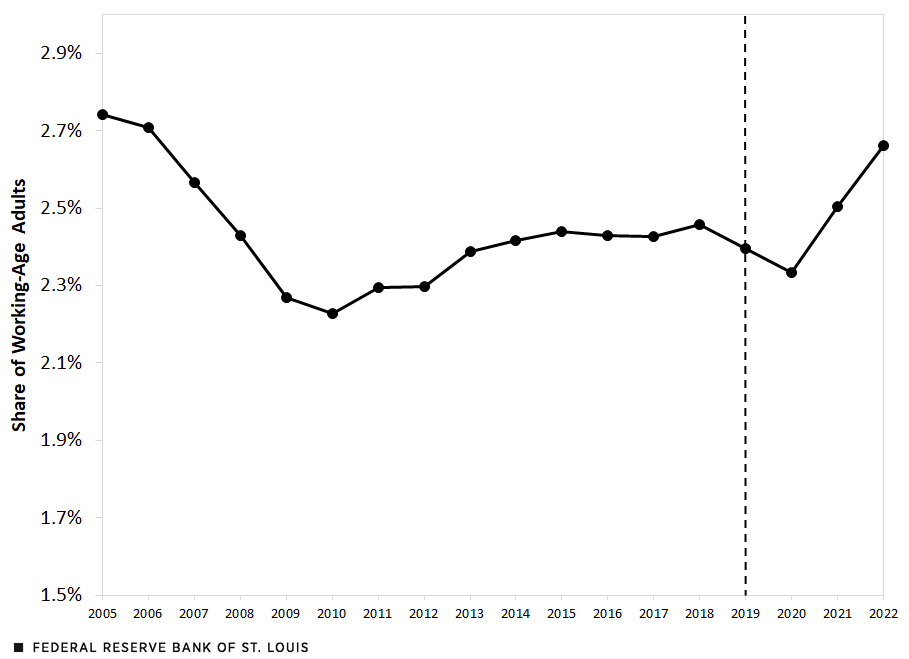

The annual share of people moving from one U.S. state to another has declined substantially over the past several decades. According to our analysis of data from the American Community Survey (ACS), annual interstate migration among working-age adults (ages 18-64) fell from 2.74% in 2005 to 2.40% in 2019, a decrease of 13%. (See the figure below.) A frequently raised concern is that the decline in migration reflects a less-flexible economy: Workers are not moving to regions with better job opportunities, thereby slowing geographical reallocation and potentially lengthening recessions and hindering growth.

Rate of Interstate Migration, 2005-2022

SOURCES: American Community Survey and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: The sample comprises adults ages 18-64 in civilian households who currently live in the U.S. and lived in the U.S. in the previous year. The dashed vertical line marks the year before the pandemic.

In this blog post, we first document that in the years following the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S., interstate migration rose sharply, partially reversing the prior long-run trend, as shown in the earlier figure.For a more in-depth analysis, see our recent St. Louis Fed working paper, “Work from Home and Interstate Migration.” By 2022, annual interstate migration was 2.66%, only slightly below its 2005 value. Second, we provide evidence that the surge in interstate migration since 2020 was primarily driven by one particular consequence of the pandemic: the rise in work from home (WFH).

A Lasting Increase in WFH

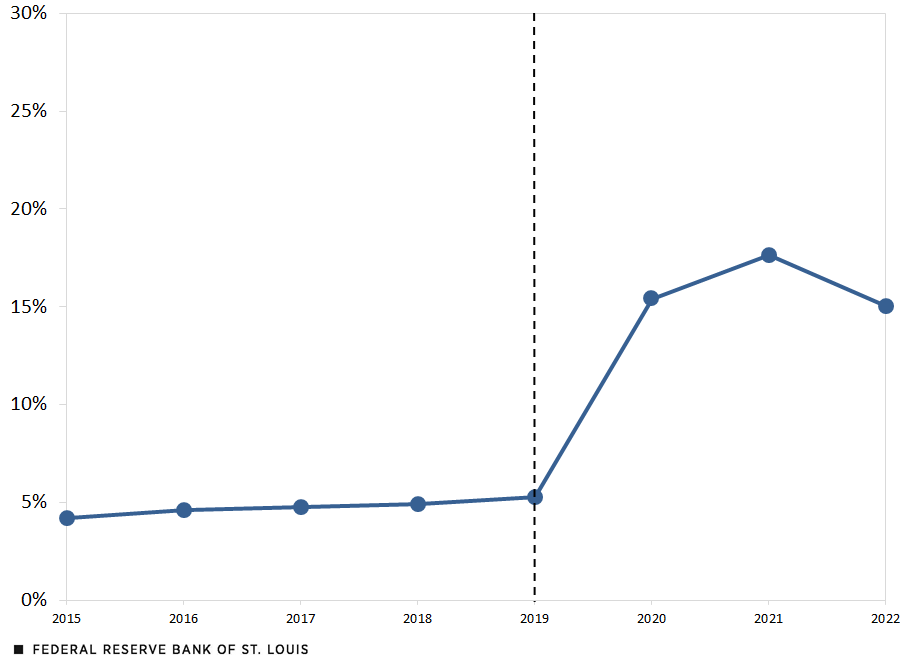

Initially, the surge in WFH was a short-run response by firms and workers to avoid health risks associated with the pandemic. However, elevated levels of full-time WFH persisted because many firms or workers preferred this new alternative to commuting. The next figure shows that by 2022, when the pandemic was beginning to wane, the share of employees who work from home full time was three times as high as in 2019.We classify an individual as WFH if they chose the answer option “Worked from home” to the question, “How did this person usually get to work LAST WEEK?”

Because WFH, especially full-time WFH, reduces the need for workers to live near their workplace, it is natural to ask whether WFH is associated with higher rates of interstate migration and whether the increase in WFH after the COVID-19 outbreak may have contributed to the increase in interstate migration.

Share of Employed Adults Who Work from Home Full Time

SOURCES: American Community Survey and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: The sample comprises employed adults ages 18-64 in civilian households who currently live in the U.S. and lived in the U.S. in the previous year. The dashed vertical line marks the year before the pandemic.

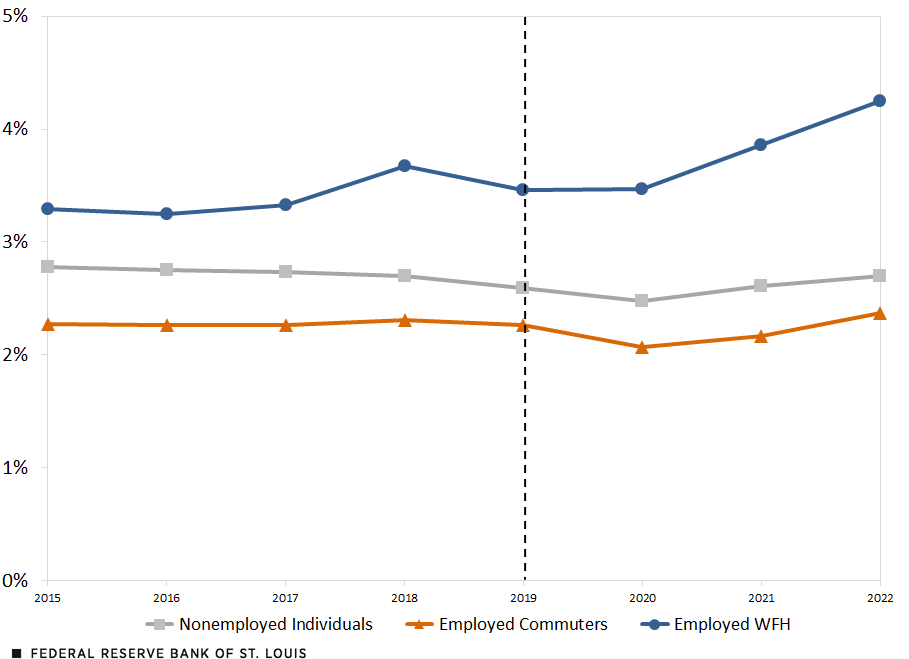

WFH and Commuting Status

To investigate this hypothesis, we separate the annual interstate migration data into three different groups: nonemployed individuals, employed commuters and employed individuals who work from home full time. As shown in the figure below, our statistical analysis shows that WFH workers had substantially higher rates of interstate migration prior to 2020. From 2015-2019, the interstate migration rate averaged 2.7% among nonworkers and 2.3% among commuters, with individual years showing minimal variation from that average. By contrast, among WFH workers, the interstate migration rate averaged 3.4%. Over that period, the gap in migration between WFH and commuters averaged 1.1 percentage points per year, which means WFH workers were 50% more likely to migrate to another state than commuters.

The gap in interstate migration by commuting status expanded after 2020. From 2019-2022, interstate migration increased 0.2 percentage points among nonworkers, 0.1 percentage points among commuters, and 0.8 percentage points among those who work from home. As a result, the gap in migration between WFH workers and commuters increased from 1.2 percentage points in 2019 to 1.9 percentage points in 2022, implying that in 2022, WFH workers were 80% more likely to migrate to another state than commuters.

Rate of Interstate Migration by Work Status

SOURCES: American Community Survey and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: The sample comprises adults ages 18-64 in civilian households who currently live in the U.S. and lived in the U.S. in the previous year. The dashed vertical line marks the year before the pandemic.

How Much Did the Pandemic Rise in WFH Contribute to the Pandemic Rise in Interstate Mobility?

In summary, the share of individuals working from home tripled between 2019 and 2022, and WFH workers were already 50% more likely to move across states than commuters before COVID-19, and that gap got even bigger during the pandemic. A simple accounting exercise suggests the rise in the WFH share alone could account for 50% of the increase in national interstate migration in 2022 relative to the pre-pandemic trend. Further incorporating the widening of the WFH migration gap explains 57% of the increase, highlighting that the rise in the WFH share is by far the dominant force driving the increase in interstate migration.

The assumption behind this exercise is that changing a worker’s commuting status would also change their interstate migration rate. Given that the large rise in WFH after 2019 did not lower the migration rate of WFH workers, this indicates that the workers who switched from commuters to WFH likely increased their migration rate to a level similar to workers who were WFH before the pandemic.

In our recent working paper, we confirm this assumption by using data from the Real-Time Population Survey (RPS), which asks individuals about their employment and living situation in the current period and in February 2020, the month before COVID-19 began to significantly affect the labor market.The RPS was developed by Alexander Bick and Adam Blandin shortly after the outbreak. The authors then partnered with Karel Mertens from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas on the survey beginning in May 2020. This provides more supportive evidence that access to WFH induces greater interstate migration. In particular, we use changes in employers’ WFH policies as an instrumental variable, finding that workers whose employers allowed more WFH for them and their co-workers were more likely both to work remotely and to migrate across state lines. Additionally, we show that both the actual level of WFH and the pre-pandemic potential to work from home—based on a state’s share of occupations that could be done remotely—are predictive of cross-state variation in out-migration and net-migration.

Implications

Our findings suggest that interstate migration will remain elevated going forward insofar as WFH remains elevated. This has the potential to significantly impact state budgets, housing markets and economic output across states, depending on where WFH workers relocate. Additionally, WFH could reduce geographic misallocation of labor by allowing workers to access employment in more-productive cities without being constrained by local housing supply. This could boost aggregate output and reduce regional income inequality. These are important considerations for future research to address.

Notes

- For a more in-depth analysis, see our recent St. Louis Fed working paper, “Work from Home and Interstate Migration.”

- We classify an individual as WFH if they chose the answer option “Worked from home” to the question, “How did this person usually get to work LAST WEEK?”

- The RPS was developed by Alexander Bick and Adam Blandin shortly after the outbreak. The authors then partnered with Karel Mertens from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas on the survey beginning in May 2020.

Citation

Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin, Karel Mertens and Hannah Rubinton, ldquoThe Impact of Work from Home on Interstate Migration in the U.S.,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, June 17, 2024.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions