Trends in Real Wage Growth among Union, Nonunion Workers

In recent years, the U.S. economy has experienced a period of high inflation and substantial nominal wage growth. While wage increases have been widespread due to a booming labor market, some workers have seen much larger gains than others due to differences in labor shortages and bargaining power across sectors and occupations.

Within the last year, collective labor agreements reached by auto workers and delivery workers have received national media attention due to the magnitude of their negotiated wage and benefit increases. About 10% of U.S. workers are affiliated with a union (PDF), but in a very tight labor market, the wages and benefits that firms offer to attract and retain workers must be competitive, and nonunion-affiliated workers may experience similar wage and benefit gains. In this blog post, I examine whether the wages of workers with union affiliation have increased at a different rate than those of workers without union affiliation.

For this, I use the employment cost index (ECI), produced by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The ECI measures the change in the hourly cost of labor to employers over time and includes wages and salaries and nonwage benefits. Labor cost information is available for union versus nonunion workers and by economic sector, among other characteristics.

Nominal and Real Wage Changes

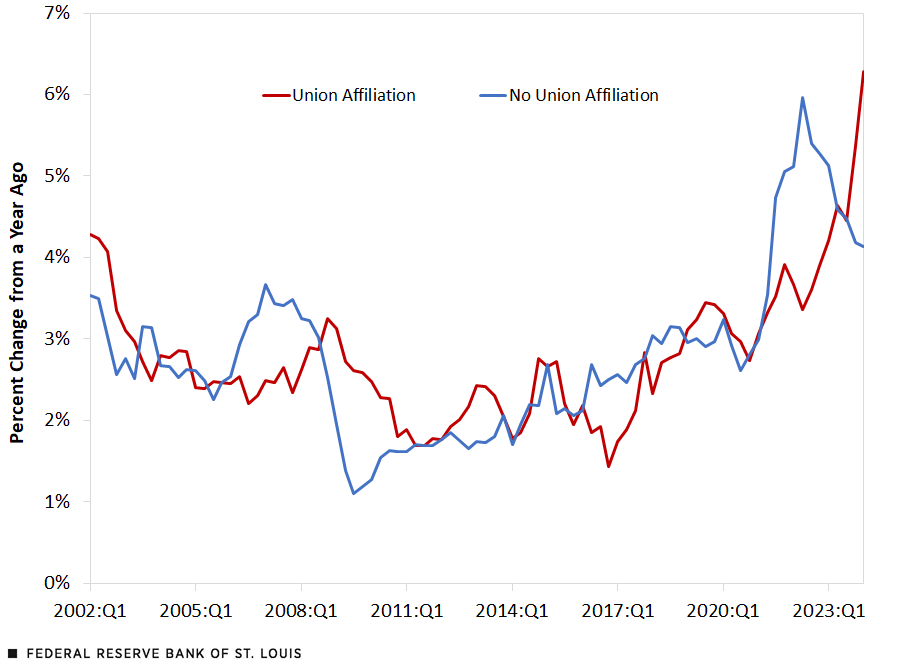

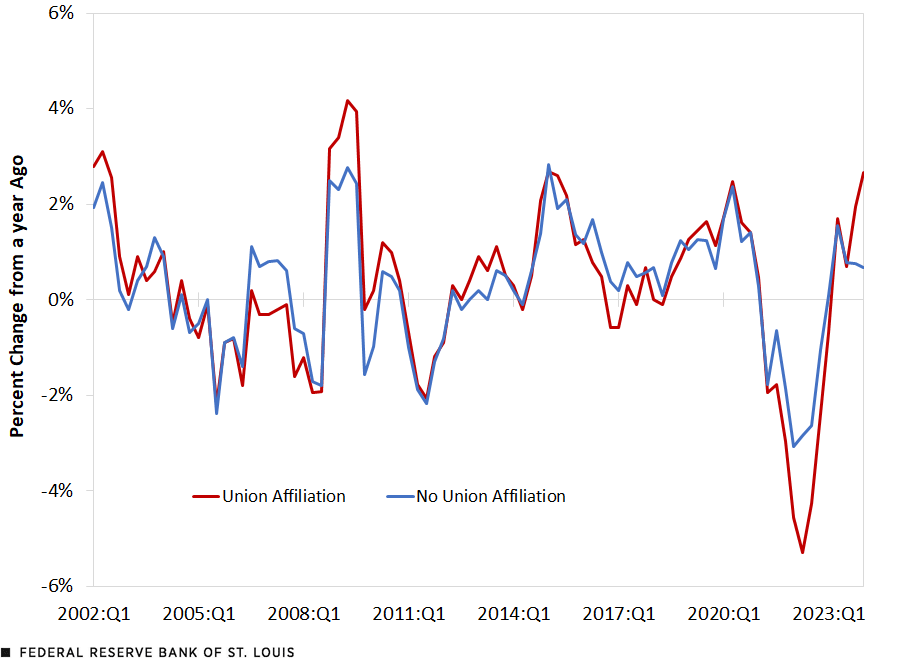

In periods of high inflation, it is important to distinguish between nominal wage gains—increases in the actual dollar amounts employers pay—and real wage gains, which measure the change in wages’ purchasing power. The following two figures show annual percent changes in the ECI, measured from the same period a year earlier, for the first quarter of 2002 to the first quarter of 2024. The first figure uses the nominal ECI, or current dollar measure, while the second figure uses the real ECI, or constant dollar measure. The red and blue lines in each figure are for workers with union affiliation and without it, respectively. At this level of disaggregation, the data are not seasonally adjusted.

Change in the Nominal Employment Cost Index: Union and Nonunion Workers

Change in the Real Employment Cost Index: Union and Nonunion Workers

SOURCES FOR BOTH FIGURES: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

NOTE FOR BOTH FIGURES: Data are from the first quarter of 2002 to the first quarter of 2024 and are not seasonally adjusted.

These figures yield some interesting observations. First, both in nominal and real terms, the wage changes of union-affiliated workers and those with no union affiliation tend to move over time in a similar way, although union workers’ nominal wage changes seem less volatile. On average, since 2002, wages for these two groups of workers increased at the same rate. Nonwage benefits and total compensation show similar trends.

From mid-2021 to mid-2023, following the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, consumer prices grew rapidly, outpacing the average annual growth rate in wages. This implies that, in real terms, wage growth was negative. In this period, the nominal wage growth of nonunion-affiliated workers was much larger than for union workers, and the real wages of union workers declined at a faster rate.

While negative real wage growth is not rare, it most often occurs at times of high unemployment and low labor demand. In this case, however, high inflation rates pulled real wage growth down into negative values despite a strong labor market.

After mid-2023, we see a return to more normal economic conditions as the disruptive forces of the COVID-19 pandemic waned, with lower levels of inflation and positive real wage growth. In addition, the nominal wage growth of union workers increased more rapidly, leading to higher real wage growth and compensating for the lost ground of the previous few years.

Accumulated Differences by Sectors

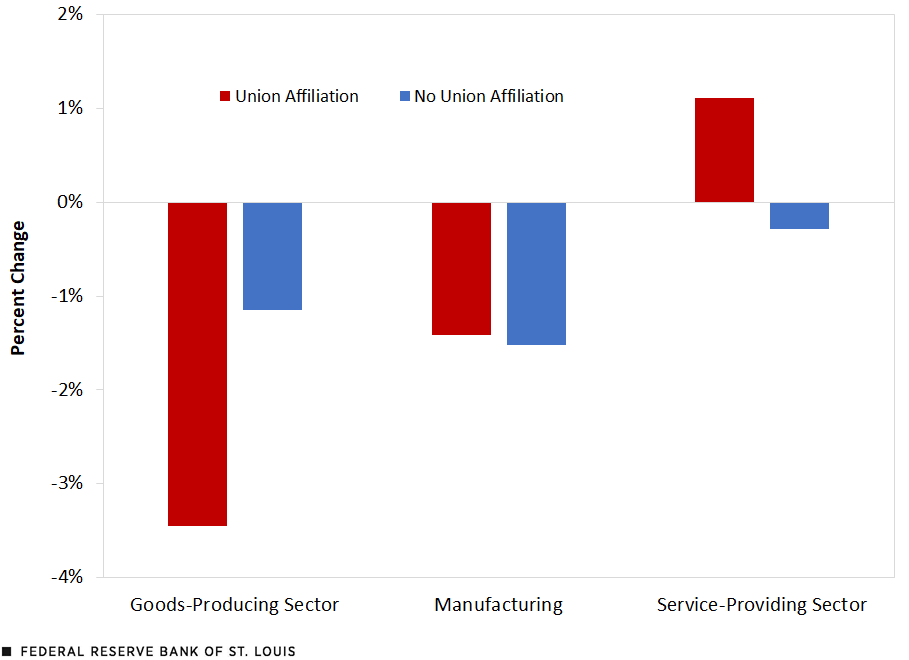

Recent labor agreements for auto and delivery workers suggest that there may be important differences across sectors of the economy. I investigate this using the ECI to look at the total change in real wages by sector from the first quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2024.

The next figure shows these changes for the goods-producing sector, manufacturing—which is an important part of that sector—and the service-providing sector. As the figure shows, real wages declined for most workers, on average, over the past five years, except for union-affiliated workers in the service-providing sector. In manufacturing, there is little difference between union and nonunion workers in the average decline of real wages, but in the goods-producing sector, union workers’ real wages declined more than those of nonunion workers.

Change in the Real Employment Cost Index for Union and Nonunion Workers by Sector, First Quarter 2019 to First Quarter 2024

SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

NOTE: Data are not seasonally adjusted.

A Return to Real Wage Growth

Changes in the patterns of consumption and demand for labor in different industries and sectors, as well as supply chain disruptions, were an important part of the surge in inflation following the initial phases of the pandemic. Despite elevated inflation, consumption was high and the labor market was strong, leading to a rapid increase in nominal wages. However, in real terms, wages for union and nonunion workers declined in the years when inflation was highest.

Over the past year, inflation and the level of economic activity in the U.S. have moderated, which is expected for an economy that is gradually returning to normal. Real wages for union and nonunion workers are now growing at a positive rate. While the real wages of union workers declined by more than those of nonunion workers in the second half of 2021 and 2022, they are now increasing somewhat faster. Some recently negotiated labor agreements for union workers include cost-of-living adjustment clauses, which would effectively put a floor on real wage changes.

Citation

Maximiliano A. Dvorkin, ldquoTrends in Real Wage Growth among Union, Nonunion Workers,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, July 15, 2024.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions