How Has Household Debt Changed since 1995?

The relative debt burden of U.S. households has fluctuated sharply since the 1990s. What might have caused this?

In a recent Economic Synopses essay, St. Louis Fed Economist Yu-Ting Chiang and Research Associate Mick Dueholm examined how changes in the supply and demand for loans may have affected the household liability-to-income ratio since 1995.

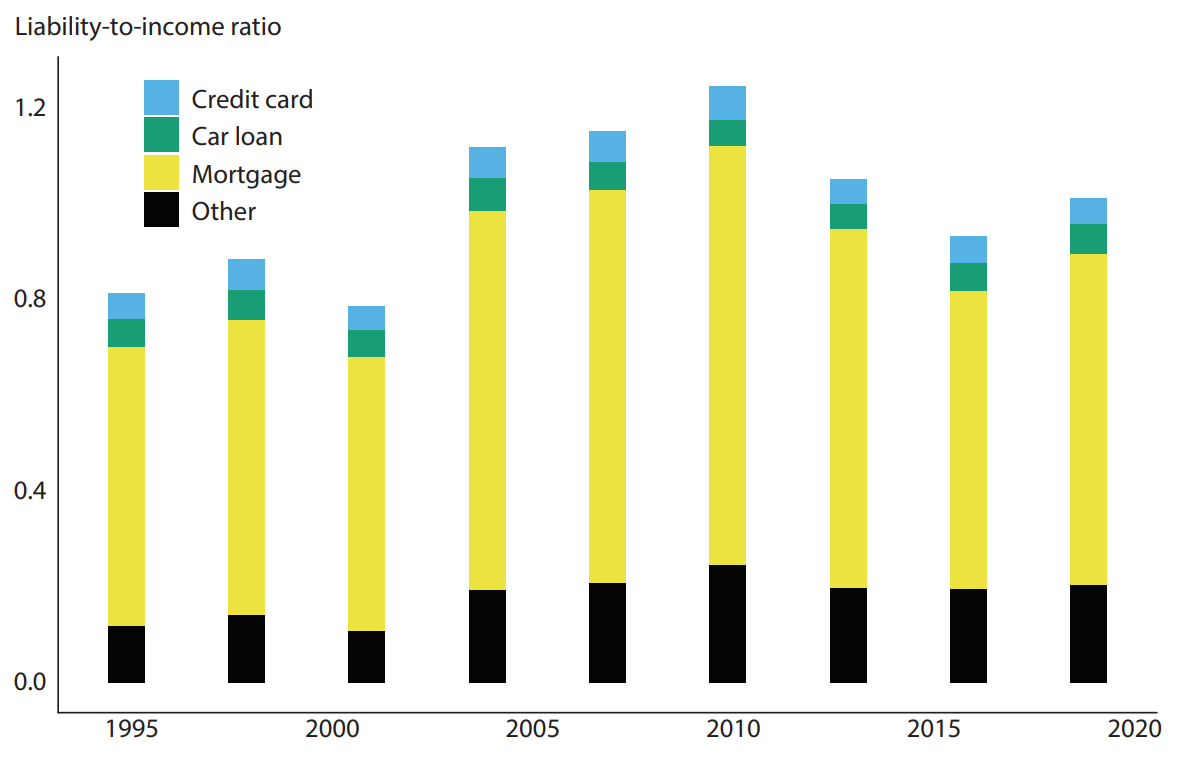

Using data from the triennial Survey of Consumer Finances, the authors tracked this ratio from 1995 to 2019, breaking down the overall ratio into four debt categories: car loans, credit card debt, mortgages and other debt.

They found that the shares of these debt categories have stayed relatively stable over time: Mortgages represented over 70% of the ratio, car loans and credit card debt each accounted for about 6% of the ratio, and other debt was about 18% of the ratio.

The figure below shows the evolution of this ratio.

Household Liability-to-Income Ratio, 1995-2019

SOURCES: Survey of Consumer Finances 1995-2019 and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: The SCF is a triennial survey.

“Total liabilities exceeded income starting around 2004 and increased until around 2010, after which they have trended mostly downward,” they wrote.

The authors then looked at percent changes in the overall liability-to-income ratio for two distinct periods: 1995-2010 and 2010-19 (2010 marked the ratio’s peak). They found that the overall ratio rose by more than 50% in the 1995-2010 period and then fell by around 20% in the 2010-19 period.

When examining the overall ratio’s component categories, Chiang and Dueholm found that most ratios for specific types of debt rose in the 1995-2010 period and then declined in the 2010-19 period.What Drove Changes in Liabilities?

To understand how changes in the supply and demand of loans may have affected the change in liabilities, the authors looked at the evolution of interest rates for each type of debt during those periods.

Chiang and Dueholm posited that if they saw an increase in borrowing and a decrease in interest rates, it would suggest the following:

- An increase in the supply of loans had a relatively important role in increasing the ratio.

- Financial institutions offered lower rates to attract borrowers.

Further, if they saw a decrease in borrowing and a decrease in interest rates, it would suggest a decline in households’ demand to borrow relative to loan supply as financial institutions dropped rates because of lower loan demand.

The authors then looked at the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate, the finance rate on 60-month car loans and the average rate on credit card plans for all commercial bank accounts. For other debt, they used the 10-year Treasury rate to represent the trend of general borrowing terms. They converted these nominal rates into real rates using inflation expectations for the corresponding horizons (e.g., the 30-year horizon for the 30-year mortgage).

The authors found that household liabilities rose relative to income and real interest rates mostly declined from 1995 to 2010, which led them to suggest that an increase in loan supply relative to loan demand happened during that period. They posited that this increased supply was likely tied to the use of new financial instruments; for example, mortgage-based securities lowered lending costs for financial institutions and expanded the supply of credit to the mortgage market.

From 2010 to 2019, household debt fell relative to income as real interest rates mostly continued to decline, which indicated that the decline in liabilities was spurred by a decline in loan demand relative to loan supply, Chiang and Dueholm noted.

“Had the decrease in debt been a result of a decrease in the supply of loanable funds relative to demand, we would have seen an increase in interest rates, as financial institutions would have asked for a higher return for issuing loans,” they wrote.

The authors posited that the decline in loan demand may have been due to the sluggish recovery after the Great Recession (2007-09)—in which consumers reduced borrowing because future income was expected to be low—and the housing bust, which affected house purchases and housing construction.

The exception to declining real rates over the period from 2010 to 2019 was the interest on credit cards, which rose instead, they observed. The authors added that this appears to reflect a reduction in lending through credit cards, possibly the result of risk reevaluation or a change in the composition of borrowers.

Citation

ldquoHow Has Household Debt Changed since 1995?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 11, 2024.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions