ALICE Households Face Continued Challenges despite Tight Job Market

Today’s tight U.S. labor market can mask certain challenges that many workers and their households face in their pursuit of economic security and a better standard of living. Looking at the portion of households under the asset limited, income constrained, employed (ALICE) thresholdThe ALICE threshold represents the income needed to cover basic living expenses. and the state of the nation’s mental health crisis could offer a greater understanding of such challenges.

To that end, this blog post also incorporates insights from our recent St. Louis Fed community development roundtable conversations held across the Eighth Federal Reserve District with workforce and economic development experts.Between May and July 2023, Institute for Economic Equity staff and other members of the St. Louis Fed’s community development team conducted 16 roundtables across the Eighth District. Community stakeholders knowledgeable about local workforce challenges and opportunities were invited to participate. These stakeholders came from a variety of sectors and included employers, nonprofit leaders, workforce development board members, representatives from regional economic development corporations, and others.

Underlying Concerns despite a Strong U.S. Labor Market

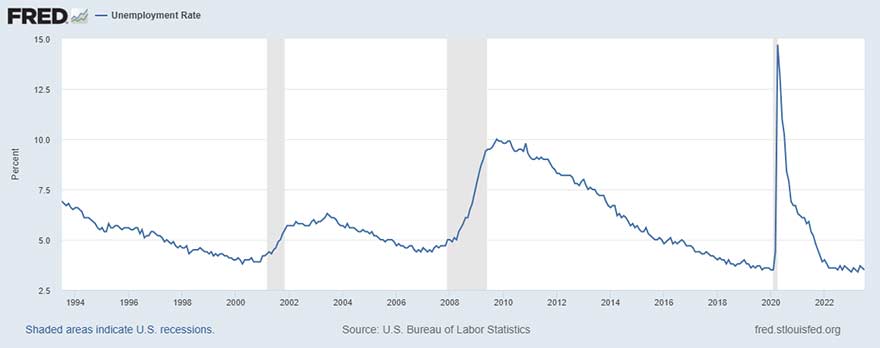

Despite the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent high inflation, the labor market has been quite resilient. The following FRED chart shows that since December 2021, the unemployment rate has been at or below 4% for 20 consecutive months.As a point of comparison, the unemployment rate was only below 4% for four consecutive months during the economic boom that lasted from March 1991 to March 2001. After 2001, there were two other periods when the unemployment rate remained below 4% for more than four straight months: six consecutive months from July 2018 to December 2018 and 13 from February 2019 to February 2020. Interestingly, when the labor market began to tighten in 2018, the share of households under the ALICE threshold stood at 42%, a single percentage point above the 2021 share.

Yet other measures suggest that even with one of the strongest labor markets since World War II, many workers and their families continue to encounter obstacles to economic security and better living standards.

The Percentage of ALICE Households Remains Elevated

The most recent estimate by United for ALICE indicates that in 2021, 41% of U.S. households could not afford the cost of basics—housing, child care, food, transportation, health care and technology—where they live. The percentage of households below the ALICE threshold in 2021 was similar to where it was pre-pandemic.

The inability of these households to earn enough to meet their basic cost of living hurts the overall economy. For example, if the head of an ALICE household doesn’t have enough food, that person functions poorly each day and the economy gets a less productive worker who may need social service assistance.

The Eighth District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. The shares of households below the ALICE threshold in five of those seven states—Arkansas (47%), Kentucky (44%), Mississippi (52%), Missouri (43%) and Tennessee (44%)—exceeded the national average of 41%.

Mental Health Is Related to Economic Security

Mental illness affects more than an estimated 50 million U.S. adults. From medications and hospitalization to the loss of productivity, mental health issues can be costly. Concerns about mental health and the lack of access to mental health care emerged during our roundtable discussions, especially as it relates to the ability of vulnerable workersThe Institute for Economic Equity defines vulnerable groups as follows: young adults (ages 16-24), all adults with no more than a high school diploma, Black men and Black women, white women, and Latino men and Latina women. Other groups and communities that face systemic and structural hurdles include out-of-school young adults, people with a disability, and American Indians and Alaska Natives. Rural workers and workers living in core urban areas are included. The adults in ALICE households are typically vulnerable workers. to find and maintain a job.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of severe anxiety in adults increased, with relatively higher rates among young adults, women and lower-income groups, according to a recent study by the Institute for Economic Equity. The study found that the unemployment rate, among other factors, contributed to the changes in anxiety from April 2020 to December 2021. With the decrease in unemployment and a reduction in the severity of COVID-19 cases, anxiety levels have fallen from their pandemic peak, the study showed. However, it is important to understand the ongoing impact of mental health on labor market outcomes, particularly for vulnerable workers, because mental health issues and economic insecurity can go hand in hand.

Impact on Worker Productivity

Lack of Child Care Is a Barrier to Employment for ALICE Households

Having over one-third of U.S. households unable to meet their basic cost of living has a direct impact on productivity, as these families typically face inadequate housing, nutrition, transportation, and access to affordable child care. In particular, child care has become increasingly more important as women make up a larger share of the labor force: By 2013, mothers were the primary or sole earners for 40% of households with children under 18, compared with 11% of households in 1960, according to a report by the Pew Research Center.

Prior to the pandemic, almost 60% of children under age 5 (11.8 million) were enrolled in regular, weekly nonparental care arrangements (PDF). And early in the COVID-19 pandemic, a lack of child care led nearly 20% of working parents to leave their jobs or reduce their hours; at the time, only 30% of working parents had any form of backup child care in place.

Our roundtable discussions confirmed that access to child care is a prominent barrier to working parents, especially mothers. However, as one roundtable participant described, other challenges can compound the problem.

The participant’s nonprofit works, for example, with an apprentice who is a mother. Since she doesn’t own a car, the apprentice makes a lengthy commute on public transportation to get to work.

“She had an issue with homelessness. So she’s rectified the homelessness, but now (she’s) trying to find a child care situation that will allow her to have her son taken care of,” the participant noted.

Mental Health Services Can Help Improve Labor Market Outcomes

Employees with anxiety, depression and addiction tend to miss work, and 84% of U.S. workers experienced at least one mental health challenge in 2021. Even if workers with mental health challenges are present, they likely are not functioning at their best. Consider that workers who typically get a poor night’s sleep—estimated to be 7% of the U.S. workforce—result in an estimated $44.6 billion of lost productivity each year.

Some community-based organizations have addressed mental health as it relates to labor market outcomes. When asked about successful strategies to assist those trying to find a job, a nonprofit leader at one of our roundtables shared how the nonprofit program offers in-house mental health services to participants. The organization provides this supportive service not only during the job search and recruitment process but also after a program participant is hired. The first few months of a new job can be a transition period, and such supportive services can help individuals navigate challenges that may arise.

Tight labor conditions have created opportunities for workers to switch into better jobs, make wage gains or re-enter the job market after a lengthy absence. But many workers already were in a precarious situation; as the previously cited ALICE numbers reveal, 4 in 10 households couldn’t afford the basics in 2021. Investing resources to develop or expand programs and services that support ALICE households in the labor market—such as child care and mental health services—could contribute to raising their productivity and thus their living standards.

Notes

- The ALICE threshold represents the income needed to cover basic living expenses.

- Between May and July 2023, Institute for Economic Equity staff and other members of the St. Louis Fed’s community development team conducted 16 roundtables across the Eighth District. Community stakeholders knowledgeable about local workforce challenges and opportunities were invited to participate. These stakeholders came from a variety of sectors and included employers, nonprofit leaders, workforce development board members, representatives from regional economic development corporations, and others.

- As a point of comparison, the unemployment rate was only below 4% for four consecutive months during the economic boom that lasted from March 1991 to March 2001. After 2001, there were two other periods when the unemployment rate remained below 4% for more than four straight months: six consecutive months from July 2018 to December 2018 and 13 from February 2019 to February 2020. Interestingly, when the labor market began to tighten in 2018, the share of households under the ALICE threshold stood at 42%, a single percentage point above the 2021 share.

- The Institute for Economic Equity defines vulnerable groups as follows: young adults (ages 16-24), all adults with no more than a high school diploma, Black men and Black women, white women, and Latino men and Latina women. Other groups and communities that face systemic and structural hurdles include out-of-school young adults, people with a disability, and American Indians and Alaska Natives. Rural workers and workers living in core urban areas are included. The adults in ALICE households are typically vulnerable workers.

Citation

William M. Rodgers III, ldquoALICE Households Face Continued Challenges despite Tight Job Market,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 22, 2023.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions