Inventory Mismatches Continue to Be Widespread

What is the state of retail inventories at the end of 2022?

Well, at least as of the summer and then this third quarter as well, they're pretty universally higher than desired for a wide range of retailers. Retailers certainly overordered or made large orders in 2020 and 2021. And as consumer demand has been shifting back to more prepandemic levels, they're left with a big, big backlog of inventory that they really want to move out.

Why are inventories so high?

Well, you have to go back to 2020. People couldn't spend on services like going out to eat or going on vacation. So they ordered a lot of durable goods instead. That means retailers saw this big, big surge in demand. They saw their inventories fall. And they made big, big orders to try to meet that consumer demand. Now if you look at what's happening this summer, consumer demand's softening a little bit. They're spending more on restaurants and vacations and less on these durable goods. So now, retailers have these big, big orders that they made and they're just sitting on a lot of this inventory. And it's not moving as quickly as they'd like it to.

Which types of businesses overordered goods?

Well, generally it's just all retailers, these large multinational firms, these large nationwide retailers. But there are some industries that are more acutely affected than others: apparel, particularly seasonal apparel, footwear, home goods, furniture as well. These are all retailers that we've heard have these really large inventory stocks right now.

What do these large inventories mean for what consumers will pay during the holiday shopping season?

Well, retailers really don't want to sit on these inventories. A lot of these goods are seasonal. So there's really no benefit to wait until next summer. And of course, it's expensive to warehouse all these goods.

So what we've heard from our regional contacts is that they're planning discounts and that they're planning to sell a lot of goods. So these off-label stores are going to have a lot more and a lot higher quality goods than they might otherwise. And consumers are also going to see discounts from retailers trying to offload these high inventories.

Even as the worst of the COVID-19 disruptions have eased in recent months, the pandemic’s impact has continued to ripple throughout the global economy. Second-order effectsSecond-order effects refers to outcomes that come about not due to the original action, but the consequences of the original action. can still be found all over, and navigating these changes can be just as tricky as maneuvering through the initial shocks.

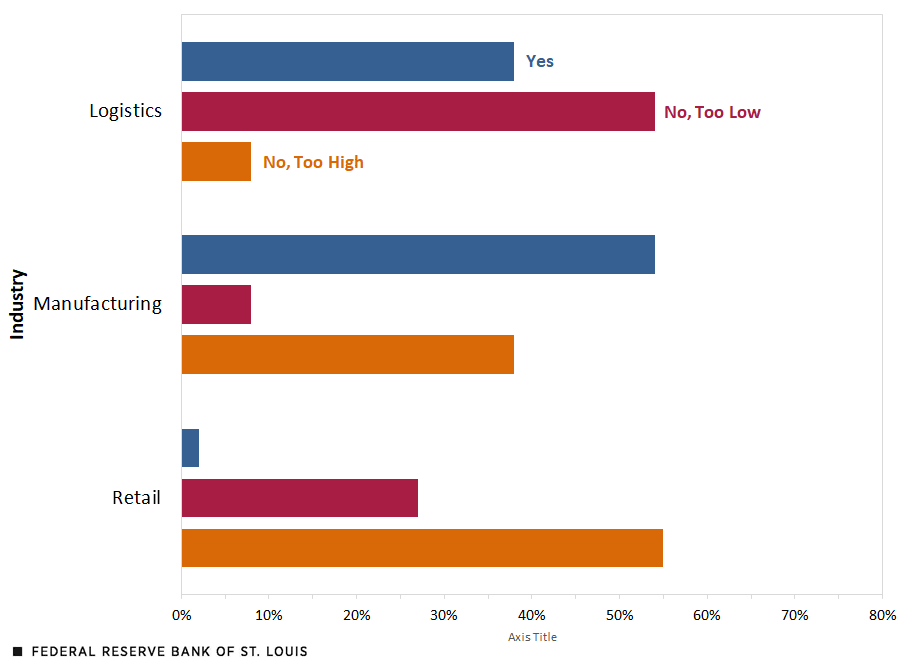

One example can be found in inventories. The St. Louis Fed’s Quarterly Survey of Regional Businesses found that a majority of respondents across the logistics (auto sales plus transport), manufacturing and retail sectors were holding inventories either above or below desired levels in the second quarter. This aligns with wider economic reporting on the same phenomenon. The industries vary, but the overall conclusions are the same: Many firms are holding too much or too little stuff.

Among Eighth District Firms, Are Inventories at Desired Levels?

SOURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Quarterly Survey of Regional Businesses (2022:Q2).

How the Misalignment Happened

How did this mismatch in inventories happen, and why is it persisting nationally even as the global economy continues to grow?

To understand better, we need to go back to spring 2020. Widespread lockdowns disrupted supply chains and—just as important—led to new spending patterns. Households spent more on durable goods and less on services. At the same time, U.S. manufacturers and retailers struggled to produce and import key inputs and finished goods. Firms that used just-in-time (JIT) inventory management faced particular difficulties; JIT calls for firms to hold only the goods they need, when they need them. This increases efficiency but relies on a steady flow of goods. If the flows are disrupted, firms find themselves without needed inventory.

In response to these disruptions, firms ordered aggressively to meet demand. As shown in the figure below, wholesale inventories have posted strong growth since July 2020, and the rate of monthly growth has increased over this time as backlogs eased. Monthly growth peaked at 2.8% in February 2022—the highest on record. These inventory increases are especially pronounced when focusing on sectors less hindered by supply shortages. Retail inventories excluding autos saw even stronger monthly growth over this period, peaking at 3.6% growth in 2021.

Wholesale and Retail Inventories Have Rebounded Since July 2020

Despite all this, consumer demand remained so strong that retailers’ inventory-to-sales ratios fell below historical averages. (See the figure below.) This ratio can be thought of as the number of months of inventory that a retailer has available. In mid-2021, retailers had only 1.1 months’ worth of inventory on hand—the lowest on record. While the ratio has risen to 1.2 as of July 2022, it is still well below the typical pre-pandemic range of 1.3 to 1.5.

In contrast, the inventory-to-sales ratio for manufacturers is above the pre-pandemic trend. Like retailers, manufacturers have added record amounts of inventory during the pandemic. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Inventories Index reported strong inventory growth in recent months, with the index reaching 52.8% in July 2022—the highest level since July 1984. For manufacturers, the need to increase inventories to withstand supply chain disruptions is even more pronounced than for retailers; shortages in any key input can result in significant production delays. As a result, the pandemic has spurred firms to stockpile inputs in an attempt to avoid the risks of just-in-time delivery.

Manufacturers Have Stockpiled Inventories to Withstand Disruptions

What Comes Next?

Higher inflation and new shifts in consumer behavior have created new uncertainty for retailers and manufacturers. Consumer spending on services has continued to rise, and inflation has softened demand for some durable goods that saw growth during the pandemic. Because of this, some large retailers have found themselves with unwanted inventories ordered long ago. These retailers face a choice between storing excess inventory or offering discounts to move these goods—both of which come with downsides.

For manufacturers, there is concern that the shifting economic environment might lead to unwanted high inventories. While carrying more inventory helps soften the impact of supply disruptions, high inventories bring costs of their own. Storing extra inventories can be costly—firms need warehouse space, as well as the transport and labor to move their excess goods. Once stored, firms may need to lower prices in the future to offload excess goods.

The ISM New Orders Index contracted in July for a second month in a row. Still, long lead times for key products remain an issue, meaning that manufacturers, like retailers, remain in the uneasy position of worrying about inventories both above and below desired levels.

Notes

- Second-order effects refers to outcomes that come about not due to the original action, but the consequences of the original action.

Citation

Nathan Jefferson, ldquo Inventory Mismatches Continue to Be Widespread ,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 27, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions