What Are Financial Market Stress Indexes Showing?

Earlier this year, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis revised its Financial Stress Index to account for the pending demise of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). Many replacement rates were suggested by regulators and market participants, but, following recommendations from then-Federal Reserve Governor Randall Quarles and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, we chose to replace LIBOR with the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). The change affected two series used in calculating the index: (1) the spread between the three-month LIBOR and the three-month overnight index swap (OIS) rate; and (2) the LIBOR-based three-month Treasury-Eurodollar (TED) spread. In each instance, we replaced LIBOR with the equivalent SOFR rate.

Briefly, the SOFR tracks the cost of short-term borrowing using transaction data on loans—collateralized by U.S. Treasury securities—in the overnight repo market. By contrast, the LIBOR covers unsecured loans, which introduces an element of default risk for the lender. That is, credit risk matters more with the LIBOR because the borrower is not posting collateral. Still, the 90-day average SOFR rate closely tracks the three-month LIBOR rate. Why? Generally, movements in the SOFR likely capture some information on changing credit risk since lenders prefer cash over less-liquid collateral; this is evidenced by the SOFR’s comovement with LIBOR.

Divergence among the Financial Stress Indexes

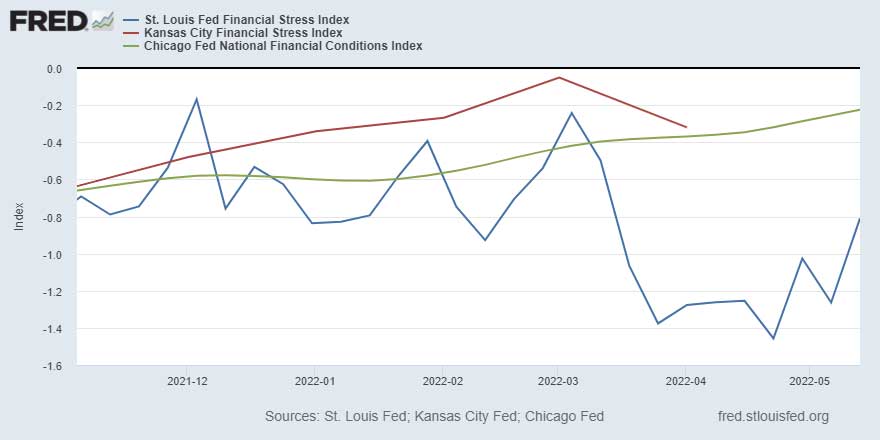

Over the past several weeks, movements in the St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index (weekly frequency) indicate that financial market stress has declined to low levels (relative to its long-run average of zero). At the same time, other indicators have pointed to increased levels of financial market stress: The figure below shows that both the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index (weekly frequency) and the Kansas City Financial Stress Index (monthly frequency, with latest release from April) have been on the rise and approaching zero.

Rising levels of financial market stress seem consistent with recent sharp declines in U.S. equity markets, increased market volatility, and rising interest rates. These developments have occurred against the backdrop of market expectations that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) may need to increase its federal funds target rate by a sizable amount to combat inflation that remains well above the FOMC’s 2% inflation target.

Recent Divergence of Various Financial Stress Indexes

SOURCE: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data).

NOTE: Positive values denote higher-than-typical levels of stress for all indexes.

Increases in interest rates that accompany actions by the FOMC to lift its policy rate have often raised fears of slower economic growth or outright recession. These fears tend to trigger increased “risk” in financial markets. Higher levels of risk can take many forms for borrowers and lenders. These include liquidity risk (the FOMC is reducing the level of bank reserves, thereby lowering the amount of available funds to lend); credit risk (the risk that borrowers may default on loans); and interest rate risk (the risk that higher interest rates will adversely affect bank or nonbank profits).

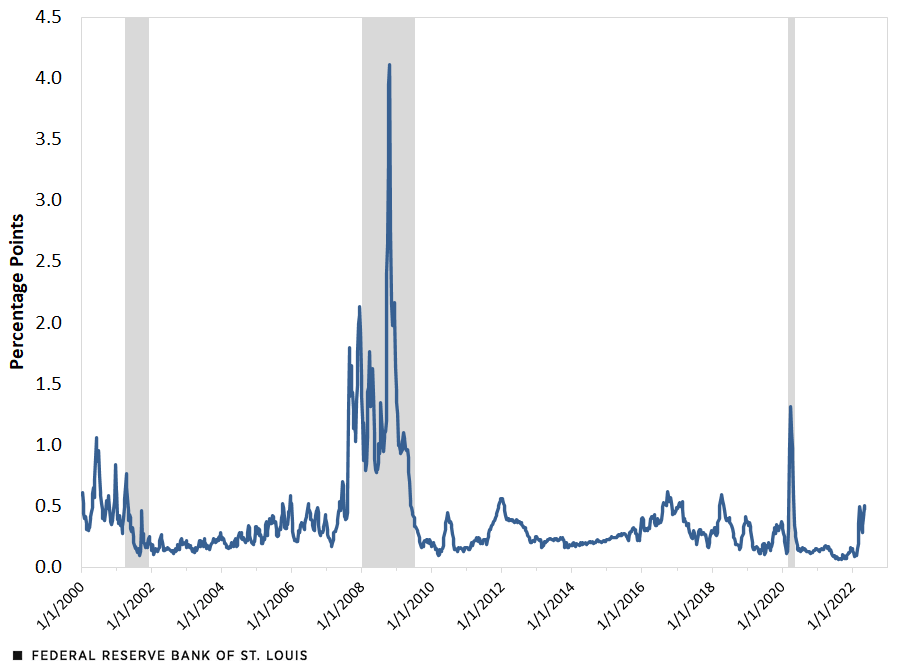

Historically, rising levels of risk are reflected in increased risk premiums that raise LIBOR rates relative to other rates. The figure below displays the time series for the TED spread—the spread between the three-month LIBOR, denominated in U.S. dollars, and the three-month Treasury bill. During periods of heightened financial stress, such as the Great Recession, the TED spread spikes as a result of rising LIBOR rates relative to Treasury bill rates.

Treasury-Eurodollar Spread

SOURCES: Intercontinental Exchange, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: This is the spread between the three-month LIBOR, denominated in U.S. dollars, and the three-month Treasury bill. Shaded areas mark the duration of U.S. recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research; the contraction’s first month is the month following the business cycle’s peak and the final month is the month of the trough.

The Impact of the Switch to SOFR

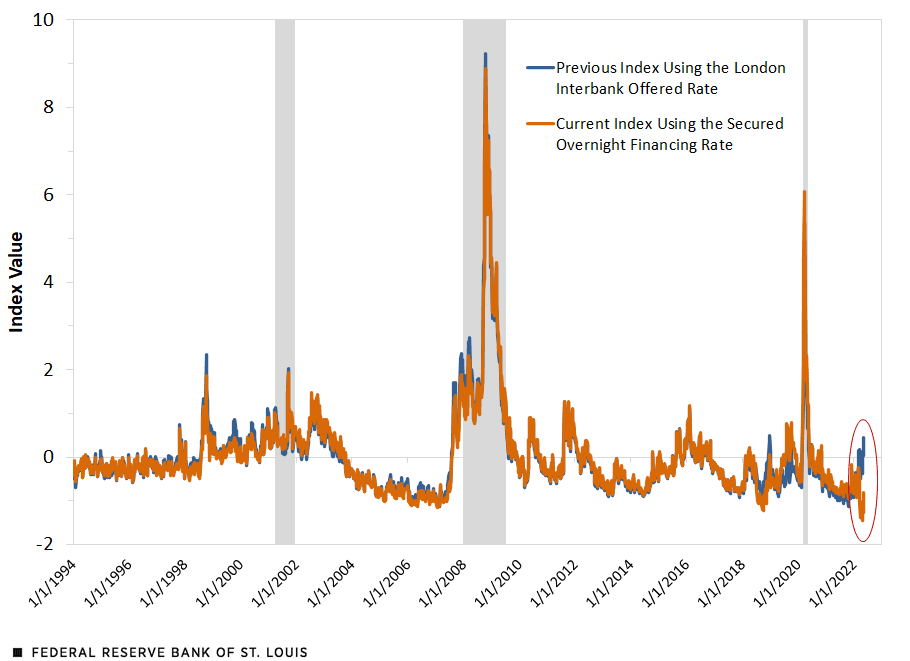

As seen in the figure below, the previous version of the St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index that includes LIBOR has diverged from the current SOFR-based version. This divergence could be signaling an elevated level of financial market risk—and thus higher levels of financial market stress—that normally accompanies periods of Fed tightening. It is also possible that there are other market dynamics at work that cause the SOFR and the LIBOR to diverge when the FOMC raises its policy rate.

St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index: LIBOR Version vs. SOFR Version

SOURCES: FRED and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: Shaded areas mark the duration of U.S. recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

As the third figure shows, temporary divergences between our indexes have occurred in the past. Interestingly, the previous divergence in 2019 occurred after a period of Fed tightening. Over time, though, the correlation between the previous version using LIBOR and the current version using SOFR is almost perfect—0.99, as of last week. Ultimately, time will tell whether the signal from the SOFR is generally similar to the signal from the LIBOR during periods of elevated financial market stress. Either way, it is likely that the current St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index will continue to be an important indicator of financial market stress—it contains dozens of series beyond its SOFR-backed spreads that should capture changing market stress levels, after all.

Citation

Kevin L. Kliesen, Michael W. McCracken, Trần Khánh Ngân and Devin Werner, ldquoWhat Are Financial Market Stress Indexes Showing?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 24, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions